Wreck of the 'Guardian'

'HMS Guardian' sailed for New South Wales in September 1789 with supplies and provisions desperately needed by the recently established penal colony. She never arrived. Crippled by an iceberg in the Great Southern Ocean, she limped back to the Cape where she was beached, never to sail again. Most of the crew and cargo were saved, through the quiet leadership of a remarkable 26-year-old commander, Lieutenant Edward Riou.

Gary L. Sturgess

9/26/202514 min read

HMS Guardian

In April 1789, weeks after the return of the First Fleet ships with news that the recently established penal colony was in need of provisions, a 44-gun naval vessel named HMS Guardian was fitted out as a storeship.

Command was given to a promising young naval lieutenant, Edward Riou, only 26 years of age, who had first crossed the Great Southern Ocean 13 years before, as a midshipman on Cook’s final voyage.

With a crew of 92, Guardian was operating at less than a third of her usual complement, but this was still significantly more than a merchantman of comparable size. Apart from her cargo, she was carrying a large greenhouse filled with plants selected by the legendary botanist, Sir Joseph Banks, seven men who had been recruited to serve as convict supervisors (including two gardeners personally chosen by Banks), a second chaplain and 25 convicts with trade skills.

She arrived at the Cape of Good Hope in late November, taking on cattle and horses, pigs and poultry, before sailing for New Holland on the 11th of December. Riou planned on taking her down to 44 degrees south:

'. . . in order to better ensure the steady westerly wind that I had experienced in Cook’s last voyage – knowing that by being in lower latitudes I should be most probably only subject to more variable winds without the advantage of finer weather'. [2]

Ten days later, at 42 degrees, they saw their first icebergs. Riou was surprised, because Cook had not encountered ice until they were at 53 degrees. There was a thick fog and heavy drops of water fell from the rigging. On the afternoon of the 23rd, they encountered a large island of ice, and Riou sent out two of the boats to collect small pieces to refresh their water supply.

The Island of Ice

With night coming on and fog closing in, Riou bore away to the north-west to put distance between them and the iceberg. An hour and a half later, as he was finishing a cup of tea in his cabin, Riou felt a blow to the helm and rushed on deck to find the crew in a state of terror. Towering over the lee bow, twice as high as the masthead, was the iceberg.

The ship slowly mounted a shelf, where it rested for five or six minutes before sliding back into the water. Riou thought they might have escaped relatively unharmed, until he was told that the tiller ropes were slack. The rudder had been torn away and there was already around two feet of water in the hold.

He ordered the men to the pumps and the ship to be lightened. The cattle and their stalls were thrown overboard to clear the deck, although two stallions, terrified and unmanageable, remained at large for the time being. A sail was ‘thrummed’ or quilted with rags and rope, and put under the hull just before dawn in an attempt to seal the holes, but the water continued to gain. When a gale came up, ‘the Sea making Breaches over the Ship Gunwal & Covering the people at the pumps’, Riou was not hopeful that she could be saved. He later wrote of his growing despair:

'In the Evening I attended the pumps for Two or Three hours, but I found now that I myself began to fail, perhaps from great bodily Strength & capable of Enduring great fatigue I should have been able to have held out with the least rest, but I could no longer propose plans that would appear successful. . .

About midnight I was wearied of my Situation & found myself fairly knocked up. tho’ My Mind now began to feel the dreadful Effects that must Ensue. Without Vanity I may say that I was prepared for my own Exit as well as possible but the Scenes which figured themselves to Me of What must happen in the Minds of the people, & how differently the feelings of men might be acted upon. . .' [4]

He spent some time with his Master, Thomas Clements, talking over the options, and as he returned to his cabin in the early hours of the morning, he was approached by some of the men who said they could pump no longer. Christmas Day broke and Riou ordered the boats prepared. Believing that there was ‘no possibility of my remaining many hours in the world’, he retreated to his cabin where he wrote a brief note to the Secretary of the Admiralty:

'If any part of the officers or crew of the Guardian should ever survive to get home, I have only to say, their conduct, after the fatal stroke against an island of ice, was admirable and wonderful in everything which relates to their duties, considered either as private men, or in his Majesty’s Service.' [5]

Abandoning Ship

They had five boats – the launch, two cutters (large and small), and two jolly boats – but these couldn’t carry half of the crew and passengers. Riou could think of no way of deciding who should leave, and fully expected that there would be a breakdown in discipline as the moment of departure approached. It was clear that he must remain, his reasoning as follows:

'Was it possible for myself & some others to embark in the Boats and leave the Rest on Board, I shd always consider myself almost in the same Light as their Murderer; seeing I have been the Cause of bringing them into this Danger; But this wd not be the Case; for when they see me quiting the Ship, they all wd immediately crowd into the Boats & wd either sink them; or it wd be impossible to take Provisions and water sufficient to support us until we shd be able to make Land; but if I remain on Board the People will not be very solicitous to quit the Ship, & those who are disposed to embark will have a better opportunity to escape, otherwise none will be saved.' [6]

The convention that the captain remained with his ship had not yet been established, and a recent analysis has argued that Riou’s decision that day played a significant part in popularising this norm. ‘Henceforth, for any captain, leaving his ship and crew to their fate meant losing his reputation.’[7]

The boats were launched in an orderly manner, but both of the cutters were dashed against the side of the ship, suffering some damage, and one of the jolly boats was dropped, killing the surgeon and two of the crew. Then, as the boats returned to the ship to collect more water and provisions, there was a panic. Twenty or thirty men threw themselves into the choppy, ice-cold sea. Only two or three were successful in reaching the boats.

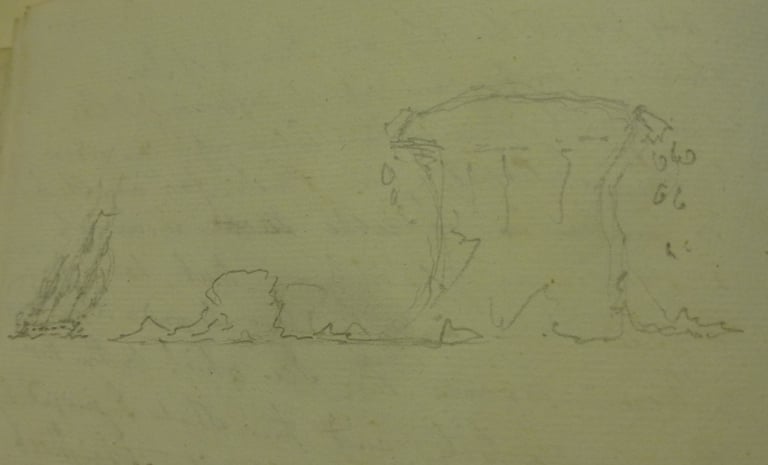

Riou's Sketch of the Iceberg (3)

'The Perilous Situation of the Guardian' [8]

The crew were organised into watches, taking turns at manning the pumps. Riou arranged for them to be supplied with hot tea and hearty food, wine and spirits, served by a terrified ten-year-old, Elizabeth Schaeffer, the daughter of one of the convict superintendents, who waded through freezing water up to her waist.

Some days the men pumped well, other days they were ‘jaded’, sometimes they were too exhausted and occasionally too drunk. The wooden pumps were worked hard and frequently broke, requiring them to be taken out of service and repaired. There were days when great waves rolled over the ship, washing down into the lower decks and preventing the pumps from being used.

The men struggled to stay in front: by early January, water had completely filled the orlop deck, and the stern was so deep that the ship had difficulty in moving. Towards the end of the month, however, Riou got the second fothering sail under the stern, and thereafter they were generally able to keep the water within several feet of the ‘hollop [orlop] beams’. But this was only accomplished with great physical effort by men working at the very limits of their physical and mental endurance.

Riou continued to drive them, but struggled to remain positive himself. Of the 28th of December, four days after striking the iceberg, he wrote: ‘Hopes I had None’. One of the convict supervisors later claimed that at one point, Riou spoke of killing himself. [10]

Several of the men were openly mutinous, and Riou knew that he did not have the authority to pull them into line, writing in his journal when some of them were drunk, ‘It was hardly a Time to be a disciplinarian’. On another occasion, when confronted by the worst of the rebels, a seaman named Thomas Humphries, he noted: ‘I found it politic to submit handsomely’. [11]

Around midday on the 1st of January, as he was dining on bread and pork, one of the midshipmen reported that a meeting was being held forward to discuss the possibility of seizing control. There was no obvious ringleader, although as usual, Humphries was outspoken. From what the midshipman could hear, the men thought that Riou had lost his senses and wanted to kill himself by taking them in the wrong direction.

Riou ordered all hands on deck. He explained why he had changed his mind about making their way to the islands. He pointed out that none of them could navigate the ship and insisted that everything he had done had been for the good of the Guardian and her crew.

'. . . were I here alone I should be content to die – When I saw no means left to save myself – but since the foresail I have great hopes if the Ship can be Wore. . .' [12]

‘They went away Contrite & respectful’, he wrote in his one of his journals, and over the coming weeks, as the men observed his relentless efforts to save the ship, Riou was increasingly able to assert his authority. On the 14th of February, he gave Humphries a thrashing, and three days later, knocked down one of the convicts who had been of great value in assisting the carpenter but had become unruly.

As they drew closer to the southern coast of Africa, Riou worried about where they might land, and started experimenting with yet another rudder. He did not want his imperfect control of the ship to tested on a rocky shore, and hoped that they might fall in with another vessel before that moment arrived. He spent the morning of the 22nd on deck experimenting with the new rudder, but after four or five frustrating hours, gave up and retreated to his cabin for tea.

'When considering sitting down in the Cabin over my Aprés – [Richard] James told me at 11 they saw the Land – I went on the fore Castle and the St. [starboard] weather bow I saw it directly and thank God it was the only Land I knew on the Coast, it was the Cape of Good Hope - the Ship head running right for it.' [13]

Return to the Cape

She was towed into the bay by half a dozen boats and finally brought to anchor the following afternoon. It had been 58 days since their encounter with the iceberg. An English correspondent wrote of their arrival:

'Seeing an English ship with a signal of distress, four of us went on board, scarcely hoping but with busy fancy still pointing her out to be the Guardian, - and, to our inexpressible joy, we found it was her. We stood in silent admiration of her heroic commander (whose supposed loss had drawn tears from us before), shining through the rags of the meanest sailor. The fortitude of this man is a glorious example for British officers to emulate.' [14]

HMS Guardian sailing from the Downs for Botany Bay, July 1789 (1)

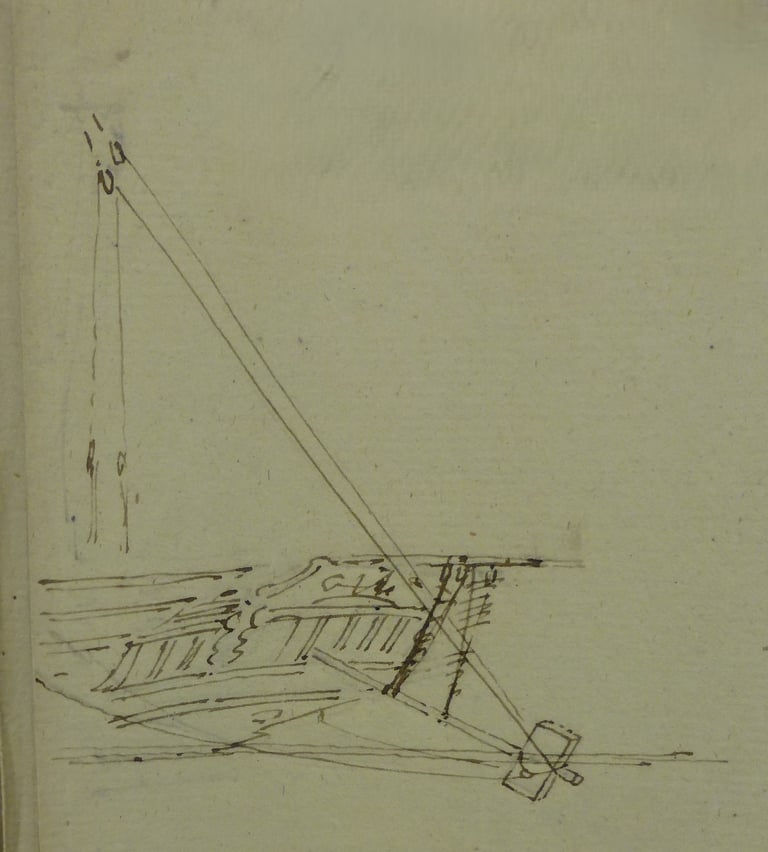

Riou's drawing of his 'steering machine' [9]

Riou sent a brief letter to the Admiralty by a ship which was about to sail for Europe, and a second to his mother:

'God has been merciful.

'I hope you will hear no fatal accounts of the Guardian – I am safe, I am well, notwithstanding you may hear otherwise.

'Join with me in prayer to that blessed Saviour who hath hung over my ship for 2 Months & kept thy Dear Son safe to be I hope thankful for almost a miracle.' [16]

Most of the men were sent back to England on the first available vessel, but Riou stayed at the Cape for another year, salvaging what stores and provisions he could, forwarding the best of them to New South Wales with the Lady Juliana and the Second Fleet, and disposing of what remained locally. He had hoped that the Guardian might be patched up well enough to take her home, but this proved impossible and in early May, Riou drove her on shore. When he sailed for England in March of the following year, he took the ship’s figurehead with him. [17]

News of the Guardian’s arrival at the Cape broke in the London papers on the 29th of April 1790, five days after the first accounts of her loss. Riou’s letter to the Admiralty was immediately sent to the King, ‘who expressed uncommon satisfaction on receiving it’. [18]

He did not arrive home until May of the following year, to discover that he was a national hero. There was the mandatory court martial at which he was honourably acquitted after a hearing that was so brief minutes were not even written up. He was presented at the next weekly levée, where the King paid him particular attention, and immediately promoted him to post captain. The London papers referred to him as ‘the gallant Captain Riou’ and he would remain a national treasure until he was killed at the Battle of Copenhagen a decade later.[19]

Captain Edward Riou, c.1800 [20]

The launch was carrying fifteen men, including the Master, who had brought with him charts and compasses, quadrants and sextants. They had been able to load two bags of biscuit, two mutton hams, two fowls, a goose, some butter, a small keg of rum and 20 gallons of water, and they swapped one of their sextants for a block of cheese with the men in the great cutter. Clements took the boat north, heading for the sea lanes used by European ships on their way to and from the East Indies, although the likelihood that they would encounter another vessel was small.

Conditions were typical for the Great Southern Ocean – ‘Fresh Gales Squally and Cold weather with high Seas Running’. Hard work in a cutter. They were covered with tarpaulins, but the men were wet and cold. On the first night, the purser wrote, it was ‘excessively cold’, and he could not get any sleep. His feet and legs were numb, like a dead weight hanging from his body.

Not knowing when they might be rescued, they ate and drank parsimoniously and by the time a week had passed, they had started drinking sea water. There was a brief insurrection by several of the seamen, but they calmed down after a forceful address by the gunner.

Then, by a remarkable stroke of good luck, early on the morning of the 3rd of January, they noticed a sail to windward. She turned out to be a French merchantman on her way home from India. They were welcomed on board and a fortnight later they were safely returned to Table Bay (at the Cape), where they reported the loss of the Guardian.

With no maps, few instruments and little navigational experience, the other boats did not fare as well. When last seen, the great cutter appeared to be sailing eastward, making for the Prince Edward Islands, thought to be around two hundred sea miles away. The small cutter remained near the ship for a time before she too headed east. They were never seen again. The second jolly boat was said to have broken up shortly after the launch sailed. Fourteen of the crew were formally listed as having drowned, with another 25 missing. Both of the gardeners were lost and four of the convicts.

Saving the Guardian

There was some disorder on the ship as the boats left. The spirit room was breached and a number of men got drunk, but the pumping continued and Riou set some of the people to work in thrumming another sail to fother the leaks. Initially he thought that they might make their way to the Prince Edward Islands, but they were desolate, and there was no reason why the Lady Juliana (which had sailed before the Guardian but not yet arrived at the Cape) should pass that way on her passage to New South Wales. Riou concluded that their only chance of survival lay in sailing north to the shipping lanes, but with no rudder, the ship was incapable of being steered and she was drifting to the south-east.

He dimly recalled that as a young midshipman, he had read about a false rudder being fitted on stricken naval vessels and charged the carpenter with building a ‘steering machine’. But when it was installed several days later, they were still not able to veer.

One of the old hands then approached Riou and explained that many years before, he had helped to steer a crippled ship with cables fitted to the masts. When these were installed, they had some manoeuvrability, but a sudden change in the wind or currents could still cause the ship to wear uncontrollably.

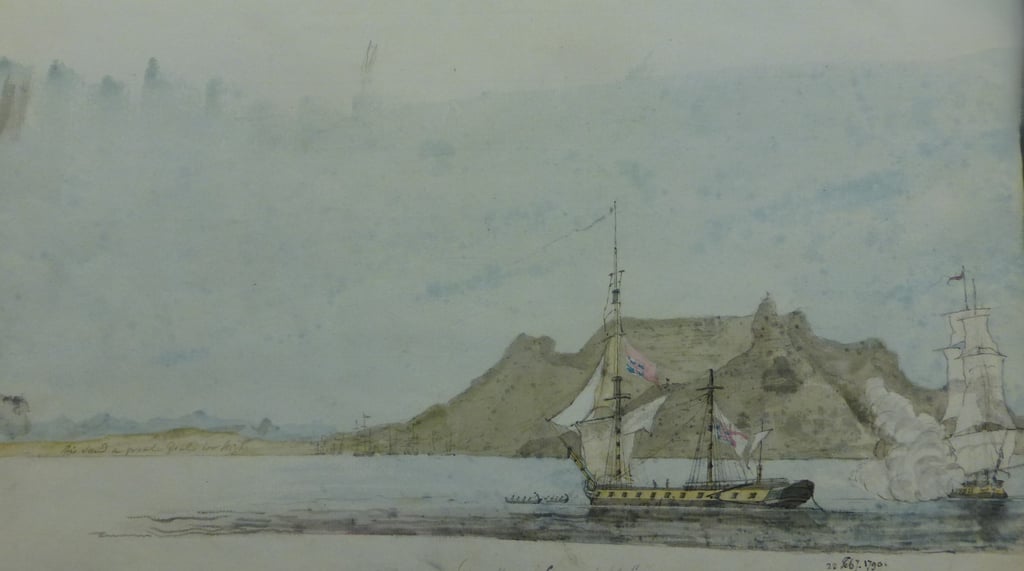

Riou's sketch of the distressed Guardian being towed into Table Bay, 22 February 1790 [15]

_______________________________

This narrative was constructed from four accounts of the voyage written by Riou – ‘The Log Book of a Voyage to Port Jackson in New South Wales, performed by Lieutenant Edward Riou Commanding his Majesty's Ship Guardian by Order of the Right Honourable the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, 21 April 1789 - 5 May 1790’ (hereafter ‘Logbook of HMS Guardian’), State Library of NSW (hereafter SLNSW), SAFE/MLMSS 5711/1, Safe 1/233a); ‘Remarks at Sea‘, UK National Maritime Museum (hereafter NMM), NM/235/ER/7/2, ‘Original draft with notes of the Logbook of the Guardian, 24 Dec 1789-23 Feb 1790’ (hereafter ‘Original draft’), NMM, NM/235/ER/7/3), and Edward Riou, ‘Narrative of the Wreck of the Guardian, 8 September to 25 December 1789’, SLNSW SAFE/MLMSS 5711/2, Safe 1/233b).

Thomas Clements, the master, also wrote an account, the original of which is missing, but published at London Chronicle 29 April-1 May and May 1-4, 1790. And the purser – Richard Farquharson, ‘Observations &c by R.F.’, NMM NM/235/ER/7/1. Shorter accounts or fragments also survive for the chaplain, several of the other midshipmen and petty officers.

See also M.D. Nash (ed.), The Last Voyage of the Guardian, Lieutenant Riou, Commander 1789-1791, Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society, 1990.

[1] Detail of Benjamin Toddy, ‘Sun Set with a View of his Majesty’s Ship the Guardian Lieutenant Rio [sic] Commander Going out of the Downs in her way to Botany Bay’, 1789, NMM PAG9678.

[2] Edward Riou, ‘Remarks at Sea’.

[3] Edward Riou, Sketch of the Iceberg, ‘Original draft’, opp. p. 2.

[4] ‘Original draft’, 25 December 1789.

[5] Riou to Stephens, 25 December 1789, published in the Times, 1 May 1790.

[6] Crowther to Dartmouth, 1 May 1790, Staffordshire County Record Office, D9W01788/V/952.

[7] Martin Rutten, Duty, Discipline and Leadership in the British Royal Navy: Edward Riou between James Cook and Lord Nelson, Munich: Peter Lang AG, 2017, p. 301.

[8] Poss. Robert Dighton, ‘The Perilous Situation of the Guardian’, c.1790, SLNSW ML 1112(a).

[9] Edward Riou, Sketch of a Makeshift Rudder, in ‘Original draft’, 28 December 1789.

[10] ‘Original draft’, 28 December 1789; Schaeffer to Nepean, 17 July 1791, transcribed from German, in John Cobley, Sydney Cove 1789-1790, Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1963, pp. 243-245.

[11] ‘Logbook of HMS Guardian’, 22 January 1790.

[12] ‘Original draft’, 1 January 1790.

[13] ‘Remarks at Sea’, Note 31, 5th last page; ‘Original draft’, opp. 22 February 1790.

[14] World, 28 July 1790.

[15] Edward Riou, ‘The Guardian Arrived in Table Bay’, 22 February 1790, Rough Sketching Book, Papers of Capt. Edward Riou (1762-1801), NMM NM/235/ER/3/9.

[16] Riou to his mother, 22 February 1790, NMM NM/235/ER/4/2.

[17] UK National Archives ADM180/7/211; Evening Mail, 13-16 May 1791.

[18] Times, 29 April 1790.

[19] General Evening Post, 12-14 & 19-21 May 1791; London Chronicle, 19-21 May 1791; Public Advertiser, 23 May 1791; Whitehall Evening Post, 26-28 May 1791; World, 28 May 1791.

[20] Samuel Shelley, ‘Edward Riou, 1762-1801’, c.1800, NMM MNT0216.

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.