What I'm Reading - March 2025

Gary L. Sturgess

3/24/20256 min read

Sara Caputo, Tracks on the Ocean, London: Profile Books, 2024.

No ships’ journals survive for the voyage of the Albemarle, the commodore of the Portsmouth division of Australia’s Third Fleet, which carried out 282 male and six female convicts to New South Wales in 1791. But the UK Hydrographic Office and the National Archives hold several ‘tracks’ made by Lieutenant Robert Parry Young, the naval agent on board that ship, recording his voyage down through the Atlantic, another marking his passage across the Great Southern Ocean, and yet another covering the coast of NSW (as well as his voyage home some months later on another vessel).

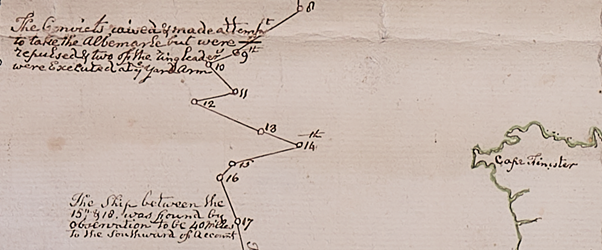

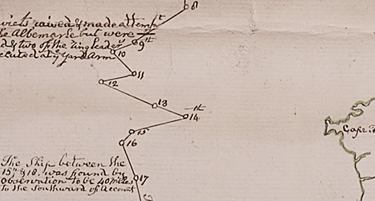

A ‘track’ is a maritime chart showing the route a ship followed in the course of its voyage, and as Sara Caputo explains in Tracks on the Ocean, by the late 18th century, they were not only used by mariners to plan their voyages through unfamiliar waters – they were used by the Admiralty to review the decisions made at sea by its naval captains, and by awe-struck boys to follow the exploits of their maritime heroes.

Parry Young’s track provides us with a visual representation of a typical convict voyage down through the Atlantic and across the Southern Ocean, but given that the ship’s log has been lost, it provides us with some information, albeit basic, about the voyage of the Albemarle.

It takes its departure from the Lizard, a peninsular in Cornwall which is the southernmost point of the British mainland, and thus fails to capture a storm several days earlier which scattered the convoy. However, it does show us the precise location to the north-west of Cape Finisterre (in Spain), where ‘The convicts raised and made attempt to take the Albemarle but were repulsed & two of the ringleaders were Executed at ye Yard Arm’. [1]

Tracks of Botany Bay ships on their outward voyage are rare. Apart from those for the Albemarle, I know of six, and one of those, for the First Fleet, was published before the fleet sailed, and is thus imaginary (and in material particulars wrong). [2]

There are another four of the outward voyage of the Sirius, and her circumnavigation of the globe in late 1788 and early 1789 when she collected provisions at the Cape, along with the homeward voyage of the Waaksaamheyd, the Dutch transport hired to carry the officers and crew back to England. These were made by the 1st Lieutenant of the Sirius, Willliam Bradley, and one of his midshipmen, George Raper. [3]

The sixth is a track of the Reliance through the Atlantic made by Henry Waterhouse on her voyage to NSW in 1795. [4] And – for the outward voyage – that is it (as best I can determine). There are many more for the homeward voyage, because the Botany Bay ships were undertaking pioneering voyages, and they were in high demand among masters intending to visit the Pacific.

Caputo documents the origins and the evolution of the track from the late Renaissance through to 20th century, explaining the meaning and the impact of these thin lines across the ‘trackless waste’ of the world’s oceans. They were, she says, a tool for storytelling, and a statement of power.

In the beginning, these charts were closely guarded secrets. In the late 16th century, knowledge of the volta do mar – the loop which sailing vessels had to undertake to make their way down through the Atlantic and return – gave the Portuguese a competitive advantage in the scramble to access the riches of the East Indies. But these secrets leaked out, and by the time of Cook’s Pacific voyages in the late 18th century, tracks were published for the (European) world to study.

The fame of Cook’s voyaging resulted in the track becoming a consumable: his voyages were inscribed on ‘pocket’ globes sold in shops; samplers embroidered by women showed where he had gone. The Australian National Maritime Museum holds one such sampler, made by Cook’s wife, but they were common throughout the late 18th and early 19th centuries. [5]

The track was not a true course, Caputo argues, but an average, a compromise. Some tracks, however, revealed the uncertainties of voyage in a wooden sailing ship vulnerable to winds and currents. Parry Young’s track for the Albemarle occasionally lurches to one side or the other – corrected ‘by the land’, ‘by observation’ or ‘by account’. Bradley's and Roper's tracks of the Sirius, and Waterhouse’s track of the Reliance includes arrows showing how the wind was blowing day by day.

But the great virtue of the track, and the reason it was popular with the general public, was its simplicity and legibility: ‘It was clear, lean, and effective at conveying its message. It was elegant, we may even say’. It captured the imagination. But over the course of the 19th century, it transformed into an instrument of surveillance.

‘They had started off as a way of indicating where seafarers had been, but now they began to be interrogated in a different way: they could show what seafarers had done, and how.’

Caputo uses 19th and 20th century court martials to illustrate her point, but Parry Young probably prepared his track as proof that the Albemarle (and the Portsmouth division of the Third Fleet, for which he was responsible) had made the best of its way to its destination, one of the primary responsibilities of the naval agent on naval transports.

Thoroughly researched and elegantly written, Tracks on the Ocean is a useful resource for those wanting to understand the voyages of the convict transports. Caputo is right to highlight the impact which tracks (and the technologies which enabled them to be made) had on the Indigenous peoples of the Indian-Pacific.

But the final substantive chapter – an attempt to explain what the track meant for women, ethnic minorities and climate change – is unconvincing. It was not only because of cultural prejudice that women did not go to sea as crew members in the 18th and 19th centuries. And track lines bore the names of the ships’ captains, not because the contribution of individual crew members was unappreciated, but because, for obvious reasons, ships were identified by their masters’ names.

One sympathizes with serious historians who are obliged to write this nonsense, no doubt because their publisher insisted upon it. To her credit, Caputo confines it to a single chapter, and a wonderful book is otherwise unaffected.

__________________

[1] Robert Parry Young, 'A Chart Containing the Track of the Albemarle, Lieutenant Robt Parry Young, Naval Agent, and of those Ships under his Orders that accompanied him, on a Voyage from England to the Cape of Good Hope on their way to New Holland, and the Track of His Majesty’s Ship Gorgon John Parker Esqr Commander from the Cape of Good Hope to England. . .’, 1791-92, UK Hydrographic Office Archive, SVY/A/W89. The other two for the Albemarle are: ‘A Chart Containing the Track of the Albemarle Transport, Lieutenant Robert Parry Young, Naval Agent, on a Voyage from the Cape of Good Hope to Port Jackson, New Holland between the 18th Augst 1791 & 13th October following, and the Track of His majesty’s Ship Gorgon, John Parker Esqr, commander, on a voyage from Port Jackson round Cape Horn to the Cape of Good Hope. . .’, 1791-92, UK Hydrographic Office Archive, SVY/A/C218; and ‘A Chart with part of the Eastern Coast of New Holland from the South Cape. . . with the Track of the Albemarle Transport, Lieut Young from Van Diemens Land to Port Jackson. . . and the Track of His Majesty’s Ship Gorgon, Capt Jon Parker, from Port Jackson towards New Zealand. . .’, UK National Archives, ADM352/754.

[2]John Andrews, ‘A General Chart of the Passage from England to Botany Bay in New Holland, 1787’, London: John Stockdale, 1787.

[3] John Andrews, ‘A General Chart of the Passage from England to Botany Bay in New Holland, 1787’, London: John Stockdale, 1787.

[4] William Bradley (att.), Untitled chart of the Sirius and the Waaksaamheyd through the Atlantic, State Library of NSW (hereafter SLNSW), Z/Cb 79/6; William Bradley (att.), ‘Southern Hemisphere showing the tracks of His Majesty’s Ship Sirius & of the Waaksaamheyd transport on board of which the Officers & Crew of the Sirius were embarked after she w/MT4as cast away’, c.1792, Mitchell Library, SLNSW Safe/MT4 140/1792/1; George Raper, 'A North & South Chart from the Lands End to the Equator', and an untitled portion of a track from the Equator to Rio de Janeiro and across the South Atlantic, c.1789, National Library of Australia, MS9433.

[5] Henry Waterhouse, ‘A Mercator’s Chart, Shewing the Track of His M. Ship Reliance from England to Rio de Janeiro’, 1795, Dixson Collection, SLNSW Z/Ca 79/2.

[6] Vivien Caughley, ‘Cook Map Samplers: Women’s Endeavours’, Records of the Auckland Museum, (2015) 50, pp. 1-14.

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.