The Shark and the Prayer Book

A prayer book found in the belly of a shark belonged to a First Fleet convict who was possibly one of the first to escape from the penal colony in 1788.

Gary L. Sturgess

6/25/20254 min read

For the passengers, the voyage of HMS Gorgon, on her return to England in 1792, was horrendous. She was carrying many of the First Fleet marines who were going home with their families, and on the passage across the Southern Ocean, they struggled to keep warm among the vast fields of ice, suffering from chilblains as well as scurvy. And then as they sailed north through the Atlantic, the children began to die, a dozen of them by the time they reached Portsmouth.

On the 1st of May, the ship was a little south of the Equator, at a time when a funeral was being held every day or two, a small miracle occurred. The crew were fishing to supplement their diet, and that day caught three sharks. As one of the marine officers, Lieutenant Ralph Clark, described it:

'. . . in the Belly of one of the them was found a Prayer Book Quite fresh not a leaf of it defaced on one of the leaves was wrote Francis Carthy cast for death in the Year 1786 and Repreaved the Same day at four oClock in the afternoon —— as the book was Seemed Quite fresh I think Some Ship must be near use now going out to Botany Bay.' [1]

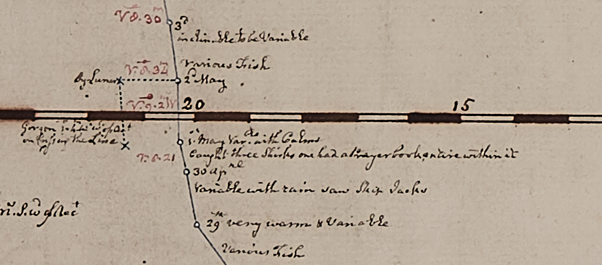

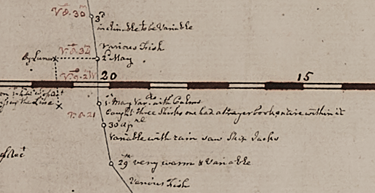

A track of the Gorgon’s homeward voyage made by a naval agent, Lieutenant Robert Parry Young, provides confirmation: 'Caught three shirks [sic] one had a Prayer Book entire within it'. [2]

Some of the marines had known Francis Carty. He had been sent out to New South Wales on the Scarborough, as part of the First Fleet, having been convicted of highway robbery at Bodmin in Cornwall in August 1786 and sentenced to death. It's likely that the judge did grant a reprieve that same afternoon before he left town, since he recommended Carty to mercy several weeks later. The death sentence was subsequently commuted to seven years transportation.

There is no evidence of Carty in the colony – he was served with fresh provisions at the Cape of Good Hope when they touched there in October 1787, but his name is missing from the 1788 Victualling List, a Who’s Who of the settlement in its first year.

Historians have speculated what might have happened to him. In her ‘biographical dictionary’ of the First Fleet, Mollie Gillen thought that it was most likely that he was lost overboard on the outward voyage, and that his messmates continued to collect his rations. Clearly the prayer book had not been in the belly of a shark for four and a half years, and she was unable to explain how it got there. [3]

But there is an alternative explanation. Carty was convicted of highway robbery at Budock Water, a small village near the port of Falmouth. This sounds like the crime of a sailor who has made his way out into the countryside while his ship was in port, committing a robbery or burglary in the hope that he could get back on board before he was caught. A significant number of these crimes can be found in the court reports of this period, and it is one of the reasons why such a large proportion of the men sent to New South Wales were seamen.

The hypothesis that Carty was a seaman is supported by the fact that on the outward voyage, he was placed in a working mess with five other men, four of whom (at least) were ‘used to the sea’ – two seamen, a ship’s carpenter, and a man who was working on a ship at Wapping when arrested. The masters of the transports employed convicts with maritime experience to work alongside the crew throughout the voyage, allocating them to ‘working messes’ for ease of administration. (See newsletter on Convict Messes.)

If Carty was a seaman, then he might have escaped on one of the First Fleet transports in May 1788. While the 1788 victualling list was prepared shortly after arrival, a number of convicts absconded in those first few weeks ashore. One of these men was later found to be living with Aboriginals, but this was extraordinarily rare, and the others simply disappear from the record. They could not have survived in the bush on their own, and it is possible that they were concealed and supported by some of the seamen. Governor Phillip wrote:

'Several convicts have got away from this settlement on board of the [First Fleet] transports. . . for convicts can remain in the woods many days before a ship sails; or they may be secreted on board in such a manner as to render any search ineffectual.' [4]

On this interpretation of the evidence, Francis Carty carried his prayer book with him when he escaped, and in late April 1792, whilst sailing through the Atlantic in some other ship, he lost this treasured possession overboard. The fact that it was found at all, let alone by men who had known him, is remarkable.

____________________________

[1] Paul G. Fidlon, et. al. (eds.), The Journal and Letters of Lt. Ralph Clark, 1787-1792, Sydney: Australian Documents Library, 1981, p.233.

[2] ‘Track of the Gorgon, from A Chart containing the Track of the Albemarle Transport, Lieut. Robt Parry Young, Naval Agent, and of those Ships under his Orders that accompanied him on a Voyage from England to the Cape of Good Hope on their way to New Holland, and the Track of His Majesty’s Ship Gordon, John Parker, Esqr Commander, from the Cape of Good Hope to England. . .’, UK HO Archives, SVY A-w89 Hg

[3] Mollie Gillen, The Founders of Australia: A Biographical Dictionary of the First Fleet, Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1989, p.403.

[4] Phillip to Nepean, 22 August 1790, UK National Archives, CO201/5/202a-203.

Robert Parry Young's Track of the 'Gorgon', showing where they caught the shark with a prayer book inside.

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.