The Men on Shore That Day

The names of the men who landed in Sydney Cove the 26th of January 1788 are mostly unknown, all but half a dozen officers, two convicts and two seamen from the 'Sirius'. But an obscure document in the NSW State Archives provides us with another ten names of men from that ship, mariners and marines, who probably went on shore that day.

Gary L. Sturgess

8/31/20244 min read

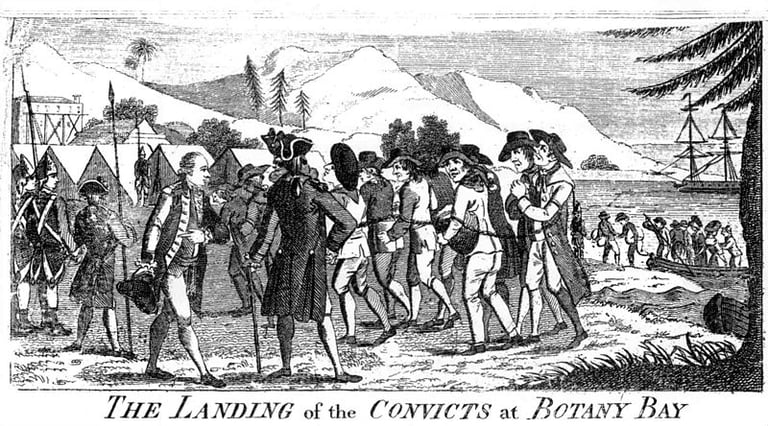

26 January 1788 – the day when the British first went ashore in Sydney Cove to establish a permanent settlement – has long been commemorated by European Australians. Understandably, indigenous Australians regard it as the start of the invasion. A spirited debate is now underway about how 26 January should be remembered: what is beyond dispute is that is one of the most significant dates in the human occupation of the continent.

At first light on the morning of 26 January 1788, Governor-elect Arthur Phillip and an advance party of grenadiers from the marine detachment, made their way ashore on the west side of Sydney Cove to secure the landing place and mark out the basic lines of the intended settlement.

They were followed by boatloads of seamen, marines and convicts selected for their trade skills, who began the work of clearing the ground of rocks and trees, and erecting marquees and tents for the marines and the male convicts who were to be landed the next day.

Of the men who went ashore that first day, very few names are known. Among the officers, Arthur Phillip; his aide de camp, naval lieutenant Philip Gidley King; engineer and astronomer, marine lieutenant William Dawes; and the commander of the Supply, the ship which had brought them around from Botany Bay, naval lieutenant Henry Lidgbird Ball.

Of the marine guard, only the two officers are known, Lieutenants George Johnston and William Collins, and none of the men they led.

There were around 50 convict artisans on board the Supply that day, and of these, only two names are certain, Thomas Yardley, a gardener, and Will Haynes, a cabinetmaker. They had joined the Supply in November, shortly after the fleet had left the Cape of Good Hope, when Phillip shifted across to the small tender. He was hoping to arrive in Botany Bay with a group of tradesmen, to start work on the camp before the rest arrived.

Two other convicts would later claim that they were present on the 26th of January. James Ruse told a NSW court in 1827 that he had been the first Englishman to set foot on New Holland, saying that he carried Captain John Hunter ashore (or in another account, Lieutenant George Johnston). Shortly before he died a decade later, the story got better: now it was claimed that he had carried Governor Phillip ashore.

In 1834, when the daughter of another First Fleet convict, Henry Kable, died, it was reported that he had been the first man to set foot in Sydney Cove. With time, this would also be improved, with the family later claiming that Kable had carried Phillip ashore on his shoulders. There are problems with these stories, and it is impossible now to know whether there is any truth to them - however, Ruse was a farmer, so it is plausible that he might have been sent on board the Supply prior to sailing from Botany Bay on the 25th of January.

There were also a number of seamen and marines from the Sirius on shore that day, tradesmen and gardeners who could assist in setting up the camp. This was not by chance: there had been a deliberate policy of recruiting mariners with trade skills for this expedition. The identity of two of these men is known: Thomas Webb, a sawyer and gardener; and James Davis, a carpenter, who had also shifted across to the Supply in November.

But a legal document buried in the NSW State Archives most likely provides us with another ten names. It is a complaint by the aforementioned Thomas Webb against Charles Parker, the carpenter of the Sirius, for assault. Webb stated that he had been working on shore on the 6th of February, and was sitting down to dinner with his messmates – a meal of fish which had been sent on shore for them by the officers of the Sirius – when Parker appeared and demanded that he should have them. Webb objected and Parker struck him.

The complaint is found in a bundle entitled ‘Pardons, Conditional and Absolute, 1788-1803’, which includes copies of Phillip’s earliest pardons. Presumably, it was filed with these papers because, until courts were formally established (on the 7th of February), legal disputes relating to events on shore were submitted to Phillip for resolution.[1]

Webb explicitly states that he ‘Come on shore to dew duty January ye 26’, establishing beyond doubt that he was one of that select band. He had three messmates, one of whom was James Davis, the carpenter who had joined the Supply in November. The other two were Webb’s brother Robert, who was a gardener, and James Poate, another carpenter.

However, the petition lists another eight men, all from the Sirius, who had also witnessed Parker’s assault. Four of them were able-bodied seamen and the other four, marines assigned to the Sirius. Presumably these were another two messes of four who had been having dinner nearby at the same time.

The four seamen were Willliam Westbrook and Robert Huill (Yule or Youle), both sawyers; Walter Brady (Brody), a blacksmith; and William Walsh (Welsh), whose trade qualifications are unknown.

The marines were Thomas Scott, a sawyer and joiner; Charles Heritage (Herritage) and John Batchelor, one of whom was a weaver and the other a farmer; and James Angel, who later worked as a shingler.

These ten men had not been moved across to the Supply in November and we cannot be absolutely certain that they went on shore as early as 26 January. But given that at least nine of these ten were tradesmen, gardeners or farmers, it seems a reasonable hypothesis.

____________

[1] ‘Pardons, Conditional and Absolute, 1788-1803’, State Archives of NSW, NRS-5601.

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.