The Lost Welsh Bible

An email from a family historian uncovered a devout Welsh convict who spoke little English.

Gary L. Sturgess

9/6/20254 min read

I don’t usually do research for family historians, but when contacted this week by the descendant of a convict who arrived in 1799, the name rang a bell: a Welsh transport named William Williams, sent out on the Hillsborough for highway robbery. And when I rummaged through my Hillsborough files, it was worth the effort.

The voyage of the Hillsborough is worthy of study for a number of reasons. Despite the active intervention of Sir Jeremiah Fitzpatrick, the prison reformer and inspector of convict ships, to remove typhus-ridden convicts from the ship before she sailed, more than 30 percent of the prisoners died on the passage, one of the highest mortality rates in the history of transportation.

There was a great deal of self-organisation by the convicts on this ship – they established their own tribunal to flush out a thief, and collectively refused their rations on several occasions when they believed they were being cheated by the cook. They were brought together by Thomas McCann, an Irish sailor who had been sentenced to death for his part in the protests the previous year on naval vessels anchored at the Nore. (In the end, McCann wouldn’t sail on the Hillsborough – the sailors refused to work if he remained.)

And in addition to the convicts, the Hillsborough was carrying four missionaries on their way to the Cape of Good Hope ‘to teach Christianity to the Hottentots’. The master of the ship allowed them to distribute religious tracts among the convicts and to go down into the prison to proselytize them.

Unlike most other attempts at reforming the convicts through preaching, the missionaries on the Hillsborough had some success. According to one account written in later years:

'Among these miserable creatures the missionary brethren determined to commence a course of instruction. They were told, indeed, that if they ventured into the hold among the convicts they would certainly throw a blanket over them, and rob them of whatever they had in their pockets; but, notwithstanding this representation, the missionaries determined to make the attempt, and happily they were received with every mark of respect, and listened to with the greatest attention. By the kindness and affability of their manner they in a few days so conciliated the regard of the prisoners, that they found themselves completely at their ease among them, ventured into the midst of them without the smallest dread, and conversed as freely with them as if they had been intimate friends and acquaintances.' [1]

William Williams was one of those who attended their prayer meetings, which continued after the missionaries had left the ship at the Cape. He had been a private in the Coldstream Guards, transported for life for a series of robberies which he carried out in Hyde Park with one of his fellow soldiers.

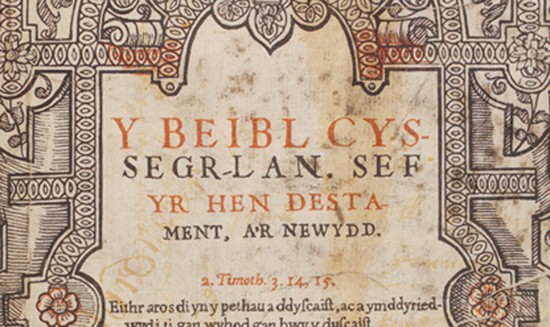

Originally from Anglesea in Wales, Williams spoke little English and carried a Welsh Bible, written ‘in the Ancient British’, as one of the missionaries expressed it. It was stolen by one of his fellow prisoners when the Hillsborough touched at the Cape and sold for eighteen pence. On their arrival in New South Wales, Williams repeatedly petitioned the missionaries for a replacement, to the point where they grew tired of him – ‘always full of complaints about his bible’. One of them suggested that he learn to read English, ‘But I have my douts weither he can, on account of his Bad pronounceation’. They tried unsuccessfully to find one in the colony, and eventually one was sent out from London.

This small community of devout convicts on the Hillsborough was dispersed when the ship came into Sydney Cove, and they stopped attending the missionaries’ meetings. They were, the missionaries explained, ‘surrounded with men, the most abandoned, and Wicked on the face of the earth’.

Williams was seriously ill when the ship came into port, and he was sent to the hospital. One of the missionaries tracked him down, and ‘found his conversation very concistant with the Gospel and very submissive, to the Divine Will’.

On discharge, he was sent to work on a farm close to Sydney, but within a year or so, he was sent up to the Hawkesbury, where he lived for the rest of his life. The missionaries in Sydney heard that he had run away and joined a group of bushrangers, but the story proved to be untrue. In March 1801, one of them reported that ‘he conducts himself with propriety’, but was (as they saw it), ‘destitute of the means of Grace’.

From what evidence is available, Williams lived a good life. He was issued with a ticket of leave in 1806, a conditional pardon in 1812, and absolute emancipation in 1821. In the muster of 1814, he is described as a landholder, with 84 acres at Pitt Town. He married a Catholic girl that same year: they would have four children, and by 1823, the ‘family’ also included two assigned convict workers. By 1817, and possibly before, he was employed as a constable in the Hawkesbury district, an indication of the respect for him the local community.

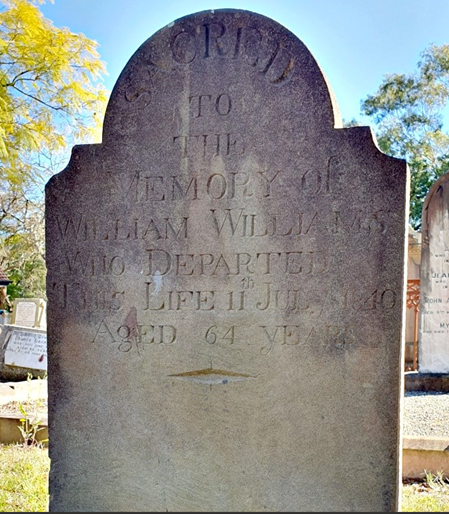

William Williams died in July 1840, at the age of 62, and was buried in the grounds of the Anglican church at Windsor. His wife Julia passed away several months later and was buried in the Catholic cemetery.

____________________

[1] Attachment to the surgeon superintendent’s journal for the Bangalore (1849), UK National Archives (TNA) ADM101/7/2.

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.