The Hunter Kangaroo

A drawing of a kangaroo, recently discovered in Dutch archives, is one of the earliest complete drawings of the animal made by a European who had actually seen one, and the earliest that can be dated. It was made by John Hunter, second captain of the ‘Sirius’, in May 1788, and possibly taken to the Cape of Good Hope in October of that year as a gift for the highly regarded amateur naturalist, Colonel Robert Jacob Gordon.

Gary L. Sturgess

6/21/20259 min read

Cook’s Kangaroo

The earliest known sighting of a kangaroo or wallaby by a European occurred on the 22nd of June 1770, when sailors from the Endeavour who had gone ashore to shoot birds to feed their sick, glimpsed an animal ‘as large as a greyhound, of a slender make, a mouse colour, and extremely swift’.

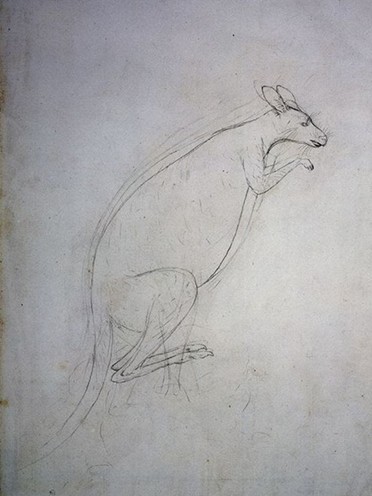

There were further sightings and a great deal of discussion about this elusive creature, until on the 14th of July, the second lieutenant shot one and brought it into camp. It was skinned and butchered, the skin preserved in spirits to be taken home, and the meat butchered for dinner, ‘which proved most excellent meat’. But before it was dismembered, Sydney Parkinson, the young artist who was supporting the expedition’s botanist, Joseph Banks, drew several rough sketches, two of which survive. [1]

When the Endeavour returned to England the following year, Banks commissioned a famous artist, George Stubbs, to paint this animal, using Parkinson’s sketches and (apparently) the skin. It was this painting, possibly of a ‘pretty face’ wallaby, which shaped the European conception of the kangaroo, and an engraving was included in Hawkesworth’s account of Cook’s first voyage, published in 1773.

Convicts and Kangaroos

The first sighting of a kangaroo by the men and women of the First Fleet was on the 5th of February 1788, when marine lieutenant Robert Kellow returned from a shooting expedition, reporting that he had seen four of ‘the animal which Captain Cook describes’, and two ‘ostriches’ (emus). [2]

Three days later, marine captain John Shea killed one of them and carried it into camp. One of the ships’ surgeons, Arthur Bowes Smyth, noted that it tasted something like venison. On the 15th, a large female was brought in, with a joey in her ‘false belly’, thought by Smyth (wrongly) to have been recently born. [3]

The new arrivals were struck by the strangeness of this animal. On first seeing a kangaroo, a marine officer wrote that it was ‘one of the most curious animals that I ever saw’. The head resembled the fox or deer, the eyes the rabbit, the front paws the monkey, and the claws were something like those of a cat. Its most striking features were the ‘extreme disproportion’ between fore and hind legs, and the large tail, which steadied them as they bounded through the bush with ‘astonishing jumps’, and served as ‘a formidable weapon’ in defence, capable of breaking the back of a large dog. [4]

A group of convicts were out in ‘the woods’ one day with a large Newfoundland dog (probably Hector, who had been left behind by the master of the Scarborough) when the dog suddenly attacked a large kangaroo:

'They observed that the animal effected its escape by the defensive use it made of its tail, with which it struck its assailant in a most tremendous manner. The blows were applied with such force and efficacy, that the dog was bruised, in many places, till the blood flowed. They observed that the Kangaroo did not seem to make any use of either its teeth or fore feet, but fairly beat off the dog with its tail, and escaped before the convicts, though at no great distance, could get up to secure it.' [5]

Having now seen these animals in the flesh, the gentlemen realised that Stubbs’ painting was not such a great representation. The French explorer, La Perouse told marine captain Watkin Tench when they met at Botany Bay in February (1788), that the Stubbs painting (or rather the engraving taken from it) ‘was correct enough to give the world in general a good idea of the animal, but not sufficiently accurate for the man of science’. [6]

Banks had compared the kangaroo to a jerboa, a small hopping rodent with large feet found in Africa, but the would-be naturalists of the First Fleet now discovered that it was a marsupial. There were none of those in Europe, and the only example then known to the British was the North American opossum – so for several years, Australian marsupials, including the kangaroo, were referred to as a kind of opossum.

The Gadigal name for this animal was badagarang, heard by the First Fleet officers as patagerang or patagorong. [7] But several of the gentlemen reported that on first encountering European livestock, the Gadigal had used the word ‘kangaroo’ to describe them. Lieutenant William Bradley wrote that around 20 men had approached the Governor’s farm (in what is now Farm Cove) in mid-February (1788), and on seeing the sheep, cried out ‘kangaroo’. Watkin Tench, who was physically present on this occasion, told the same story. The young midshipman, Newton Fowell. wrote that one of the ‘natives’ had thrown a spear at the cattle, ‘calling them Kangooroo at the same time’. The cattle wandered away from the settlement in early June 1788, at a time when there was virtually no social interaction between the two groups, so this was not a term the Gadigal had picked up from the Europeans. ‘Kangaroo’ is a European adaptation of gangurru, the name used by the Guugu Yimidirr people of the far north-east of Australia. Whatever word the Gadigal used in referring to these animals, it wasn’t ‘kangaroo’. [8]

Kangaroo Drawings from the First Fleet Period

Until recently, there were only five known illustrations of the kangaroo or wallaby that could be dated to the First Fleet period, and two of these, by Arthur Bowes Smyth, are almost identical and found in the two fair copies of his journal, held at the Mitchell Library (Sydney) and the British Library.

George Stubbs, ‘The Kongouro from New Holland’, 1772, Royal Museums Greenwich, ZBA 5754

Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China in the Lady Penrhyn. . . 1787-1778-1789', State Library of NSW, Safe 1/15

The Natural History Museum in London holds a watercolour by George Raper, a midshipman on the Sirius, the date of which is unknown, but which could have been painted as late as March 1791.

John Hunter, ‘Kangaroo, Port Jackson, 1788, Robert Jacob Gordon Collection, RijksMuseum, Amsterdam, RP-T-1914-17-238

Sydney Parkinson, ‘Kangaroo 1770’, Parkinson Zoological Drawings 4, UK National History Museum

Peter Mazell, sculp., ‘The Kangooroo’, London, John Stockdale, 1789, The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay. . ., London: John Stockdale, 1789

The fifth known drawing is a watercolour found in the sketchbook of John Hunter, second captain of the Sirius, which contains drawings of animals and birds, fish and flowers made during his time at Port Jackson between January 1788 and March 1790. The date is otherwise unknown, but later than 27 May 1788 (for reasons discussed below).

John Hunter, ‘Kang-oo-roo – or Pa-ta-gr-rang’, 1788-1790, John Hunter, ‘Birds & Flowers of New South Wales Drawn on the Spot in 1788, 89 & 89’, National Library of Australia, NK2039

A Second Hunter Kangaroo

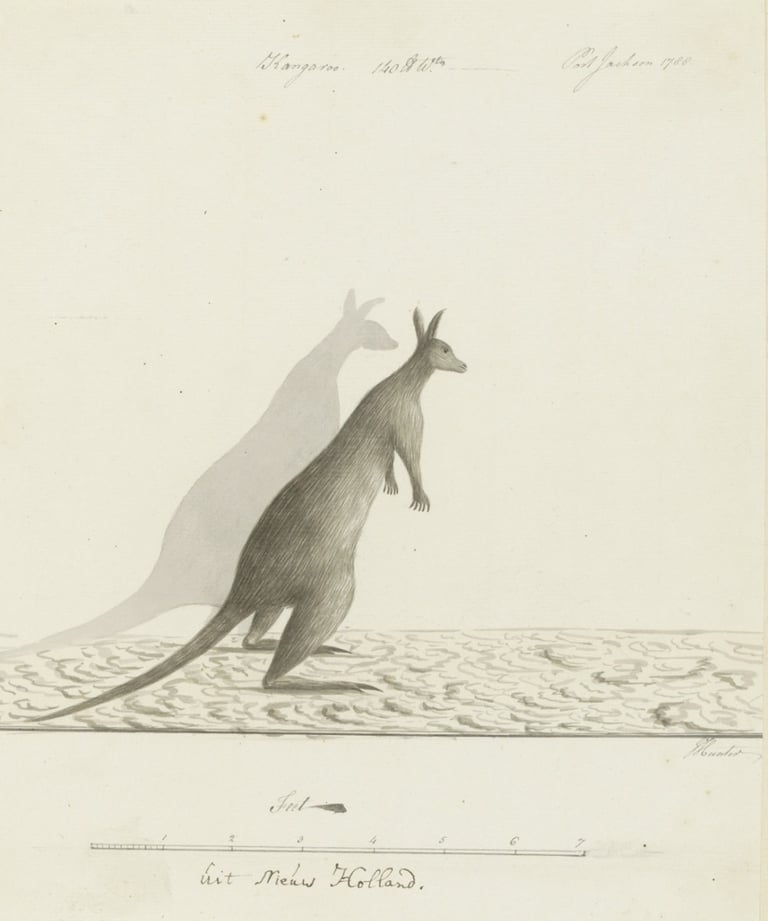

A sixth drawing of a kangaroo dated to the First Fleet period was recently discovered by the author in an archive held at the RijksMuseum in Amsterdam. It is signed by John Hunter and identified as having been made at Port Jackson in 1788. (Copy at the head of this article.)

The date of this drawing, or perhaps the date of the sketch on which it was based, can be identified precisely – 27 May 1788. An inscription alongside the title gives the weight of the animal as 140 pounds, and Hunter’s first lieutenant, William Bradley, recorded a kangaroo of that precise weight being shot on that date.

'A Kanguroo was killed which weigh'd 140 Lbs. the largest yet met with; His length from head to tail 7Ft: 3in: of the Tail 3f.t 4in: circumference of the tail at the rump 17 inches, fore legs 1 foot, hind legs 2f.t 7 inches.' [9]

Hunter also refers to this particular animal in his journal, as do a number of other First Fleet officers and gentlemen. The drawing was found in the papers of Colonel Robert Jacob Gordon, a Netherlands-born Scot who commanded the Dutch troops at the Cape of Good Hope (now held at the RijksMuseum in Amsterdam). It would have been personally presented to him by Hunter, possibly when he sailed to the Cape of Good Hope in October 1788, to purchase additional flour for the settlement.

Gordon was a highly regarded amateur naturalist, and when the First Fleet touched at the Cape in October 1787, Captain Arthur Phillip sought his advice on what plants he should take with him to the new colony. Hunter almost certainly met Colonel Gordon at that time, and we know that he made a point of seeking him out when he returned to the Cape in January 1789.

The RijksMuseum has confused Captain John Hunter with the famous British surgeon of the same name (who would later develop an interest in the reproductive organs of the Australian marsupials). There is no question that the artist in question was Captain Hunter: the unusual shadow behind the animal is typical of his animal drawings, and the autograph in the bottom right-hand corner of the sketch is identical to other examples of his signature.

The weight of the kangaroo in Hunter’s sketchbook is given as 145lbs, and even if it was the same kangaroo and there was an error in transcription (that is, 140 was rewritten as 145), the sketch in the Gordon collection must be earlier. This is the earliest dateable complete drawing of a kangaroo or wallaby by a European artist who had actually seen the animal in question.

__________________________

My thanks to Louise Anemaat, the Dixson Librarian at the State Library of NSW for comments and corrections.

[1] John Hawksworth, An Account of the Voyages Undertaken by the Order of his Present Majesty for making Discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere, Vol. III, London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1773, pp. 560, 561, 577-578; Joseph Banks, ‘Endeavour Journal, 15 August 1769-12 July 1771’, State Library of NSW (hereafter SLNSW), Safe 1/13, Vol. 2, pp. 402-403, 411-412.

[2] Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘Journal of Arthur Bowes Smyth, 22 March 1787 to 8 August 1789’, National Library of Australia, MS4568, 5 February 1788.

[3] Paul G. Fidlon, et al (eds.), The Journals and Letters of Lt. Ralph Clark, 1787-1792, Sydney: Australian Documents Library, 1981, pp. 96 & 98; Arthur Bowes Smyth, op. cit., 8 and 15 February 1788; ‘Letter from a person on board one of his Majesty’s ships’, Oracle or Bell’s New World, 22 June 1789.

[4] Paul G. Fidlon, et al (eds.), The Journals and Letters of Lt. Ralph Clark, op. cit., p. 96; Newton Fowell to his father, 12 July 1788, Fowell Family Collection, SLNSW, ML MSS 4895/1/18, p. 17; Daniel Southwell to his mother, 12 July 1788, Fair Copy of Southwell Correspondence, British Library, BL Add MS 16383, pp. 62-106.

[5] John White, A Journal of a Voyage to Botany Bay in New South Wales, London: J. Debrett, 1790, p. 181. See also Daniel Southwell to his mother, 12 July 1788, op. cit., where he reported that this dog almost had its back broken.

[6] Watkin Tench, A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay, 2nd ed., London: J. Debrett, 1789, p. 126.

[7] John Hunter, An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island, London: John Stockdale, 1793. pp. 136-137; John Hunter, ‘Kang-oo-roo – or Pa-ta-ga-rang’, in John Hunter, ‘Birds & Flowers of New South Wales, Drawn on the Spot in 1788, 89 & 90’, National Library of Australia, NK2039; ‘Vocabulary of the language of N.S. Wales in the neighbourhood of Sydney’, Library of the Society of Oriental and Africa Studies, University of London, Manuscript 41645, Part C.

[8] William Bradley, ‘A Voyage to New South Wales’, December 1786 to May 1792’, SLNSW Safe 1/14, p. 82; Watkin Tench, op. cit., p. 88; Newton Fowell to his father, op. cit., p. 17.

[9] William Bradley, op. cit., p. 109.

Given the animal’s posture and the background, it is clear that Smyth based his drawing on the Stubbs painting rather than kangaroos he had personally seen during the three months he was in the colony.

A third image, engraved by Peter Mazell, can be found in the semi-official Voyage of Governor Phillip, published in London in June 1789. There is no known drawing from which this was taken. It bears no resemblance to the Stubbs, so it seems likely that it was based on a sketch made in the colony. This could have been made as late as October 1788, when the last of the Botany Bay ships left NSW for England, carrying Phillip’s dispatches.

George Raper, ‘Gum-plant and Kangooroo of New Holland’, George Raper Collection, Natural History Museum, London

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.