The Captain's Store

It was conventional for the masters of merchantmen to operate a store on board their ships, selling tea and tobacco, shoes and articles of clothing to the crew throughout the voyage. On some of the Botany Baymen, convicts and soldiers also bought from the captain’s store.

Gary L. Sturgess

3/3/20254 min read

The system of ‘truck’ or ‘debt bondage’, where remote workers were paid in provisions from a company store, or scrip that could only be redeemed there, was scandalized in Merle Travis’s classic song written in 1946, ‘Sixteen Tons’ (covered by Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Stevie Wonder, Tom Jones, Roy Orbison and Ewan McColl among many others):

You load 16 tons, what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt

St. Peter, don't you call me 'cause I can't go

I owe my soul to the company store.

For factories and mines operating in remote areas, it made sense to maintain a store, and academic studies have concluded that they were often ‘advantageous to workers who had recently come to the communities, and who were often without money. . . They were a boon to families of improvident miners, for the wife and children could at least be sure of getting their groceries. . .’ But the potential for abuse and misunderstanding was massive, and the company store was widely reviled. [1]

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the masters of merchantmen also operated stores on their ships: a voyage of six to eight months to the other side of the world was the remotest of communities, and as with the company store, there was potential for exploitation. So much so that in 1722, the British parliament passed legislation prohibiting a captain from advancing more than half of the wages due to the crew member at the time of the sale. The East India Company went further, limiting advances in cash or kind to one third of what was due.

This aspect of the shipboard economy has been little discussed in the literature about sailing ships of this period. I can find no reference to it in Charles Abbott’s Treatise on the Law Relative to Merchant Ships and Seamen (1802) or Richard Henry Dana’s Two Years Before the Mast (1837) or The Seamen’s Friend (1845). Peter Earle mentions it only briefly in Sailors: English Merchant Seamen, 1650-1775 (1998).

However, the captain’s store does turn up in a number of sources related to the Botany Bay trade. For example, in May 1787, as Australia’s First Fleet was preparing to sail, Philip Gidley King, the Second Lieutenant on HMS Sirius, was sent across to resolve protests on several of the merchant ships which were preventing the convoy from departing. King worried that the masters of the transports (private vessels employed by government under contract) had withheld the advances conventionally paid to crew members prior to sailing on a long voyage so they could purchase stores and provisions for the months ahead. He thought the masters had done this so ‘[the crew] might be obliged to purchase those necessaries from them [the masters] in ye course of the voyage at a very exorbitant rate’.

This was somewhat unfair, since pursers routinely operated a store on naval vessels, and captains sometimes acted as their own purser - as Cook had done on the Endeavour and Bligh had on the Bounty. Indeed, some historians have argued that it was Bligh's conflict of interest in trying to serve both as commander and purser which stoked the resentment of his crew and caused the mutiny.

There are other examples of captain’s stores in the Botany Bay trade: when John McGill, a seaman on the Alexander prepared his will in October 1788, shortly before he passed away on the homeward voyage, he left his wages and possessions to another crew member, ‘after Duncan Sinclair, the said Master, is paid for various articles received from him’. One of the sailors on the Neptune (1790) claimed that the master, Donald Trail, had sold tobacco and clothing to the crew at inflated prices.

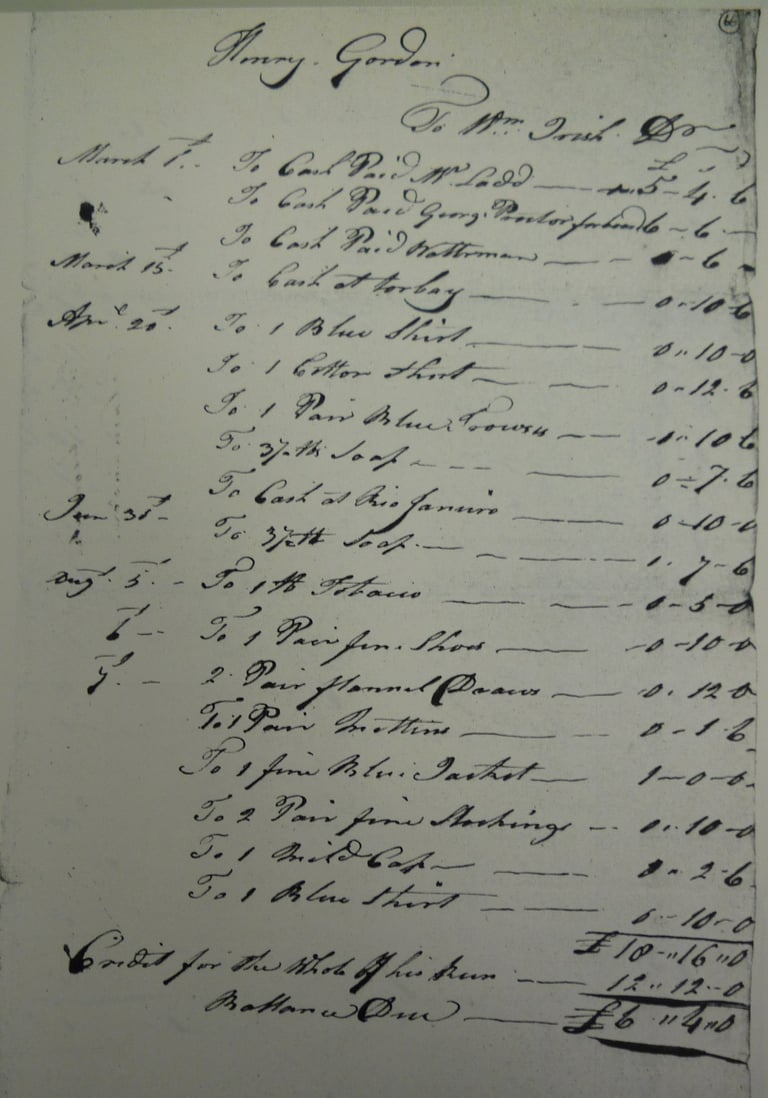

Accounts for the Salamander, which carried out government stores to NSW in 1794, show the master routinely advanced money to members of the crew whilst in port so they could send letters ashore or hire boats, and sold them clothing, shoes and knives, as well as soap and tobacco, whilst they were at sea. Some of these articles were essential to the effective working of the ship, and it is not difficult to understand why the master would want to have reserves on hand.

I know of only one reference to convicts purchasing from the captain’s store in the course of the outward voyage. The steward of the Baring (1819) testified to an inquiry into the treatment of the prisoners:

The Convicts were in the habit of purchasing Tea, Tobacco, and Sugar during the voyage from Capt. Lamb. They were informed of the prices to be charged for each Article before they had them. . . I have been Ship’s Steward Two Years and a half – the Charges are in my opinion reasonable. They are charged at the same prices to the seamen & soldiers. [2]

The potential for abuse of this system on a convict ship is obvious, but other than the Baring, I'm not aware of any complaints of exploitation. I won't be surprised if others turn up.

___________________

[1] Ole S. Johnson, The Industrial Store: Its History, Operation and Economic Significance, Atlantia: School of Business Administration, University of Georgia, 1952, p. 135.

[2] ‘Depositions in respect of complaints preferred by Laurence Halloran. . .’, Bench of Magistrates, July 1819, Colonial Secretary’s Papers. 1788-1856, Main Series of Letters Received, 1788-1826, State Archives of NSW, p. 131.

Store Account for Henry Gordon, a seaman on the Salamander (1794)

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.