Tea on the 'Lady Juliana'

From 1789, convict women were routinely supplied with tea and sugar throughout the voyage. Unless they misbehaved, these women enjoyed the freedom of the upper deck, which meant that they could brew a cup whenever the weather permitted. This was so, even on the ‘Neptune’ (1790) where the convicts were generally mistreated. The authorities did this because they believed that tea was good for their health, but it also enabled the women to carve out social spaces in what was otherwise a male domain.

Gary L. Sturgess

9/5/20244 min read

The Lady Juliana was taken up by government in December 1788 to carry female convicts to New South Wales – an attempt to partially correct the gender imbalance on the First Fleet. The government had not yet heard back from Botany Bay about the suitability of the settlement, so the Juliana was anchored in Galleon’s Reach (in the River Thames) and used as a temporary hulk for the women, while they waited to hear whether she would sail for New Holland or the remaining British colonies in North America.

In March, some of the women spoke with the surgeon, Richard Alley, about the possibility of being supplied with tea and sugar, giving up some of their salted meat provisions in return. Alley was a naval surgeon on leave, employed by the contractor William Richards to oversee the wellbeing of the convicts. He passed their petition on to Richards, arguing that the change would assist in preventing scurvy and fevers.

‘I presume the preserving their health during a long sea voyage will be desired a greater object by the legislature, through motives of humanity, as well as a political interest, than the mere difference of price of any of those articles.’ [1]

Richards sent the note to Evan Nepean, the permanent under secretary at the Home Office, along with a recommendation that each mess of six convicts be given a quarter of a pound of good common Bohea tea, three pounds of good common brown sugar, and an additional two pounds of bread a week. The cost would be covered by halving their allowance of salted meat three days of the week.

Since there was no extra cost, Treasury quickly approved, and the decision was immediately adopted as policy. In all future shipments, female convicts would be supplied with tea and sugar as a matter of course.

A National Obsession

Tea and the rituals of tea-drinking had been introduced into England in the middle of the 17th century, initially to the upper echelons of society, but over time, it had become a national indulgence. The fact that women on the Lady Juliana presumed to ask for tea and sugar, and that these articles were so readily approved, is evidence that by 1789, they were widely used by women of the lower classes. There is nothing in the archives to suggest that government officials thought of them as a luxury.

A pamphlet published in London in 1784 claimed that tea was now used in almost every family and had ‘attained the nature of an absolute necessity’. The same year, a French visitor reported that tea was drunk twice a day, and while it was still very expensive, ‘even the humblest peasant will take his tea twice a day, like the proudest’. By 1788, it has been estimated that the average working-class family spent around seven percent of their budget on sugar and three percent on tea. [2] A decade later, in his survey of the poor in England, Sir Frederick Eden wrote:

‘Any person who will give himself the trouble of stepping into the cottages of Middlesex and Surrey at meal times, will find that in poor families, tea is not only usual beverage, in the morning and evening, but is generally drunk in large quantities even at dinner.’ [3]

The Tea Table as Female Space

For the English, tea is not just a beverage, it is a social lubricant. And while men most certainly drank tea in the late 18th century, the rituals of tea-drinking and the associated paraphernalia – fine porcelain teapots and teacups – were deeply gendered. One historian has argued that:

‘No longer viewed primarily within the context of luxury commodity exchange, [Chinese porcelain] becomes familiar, domestic, quotidian. It retains strong associations with the feminine. . .’ [4]

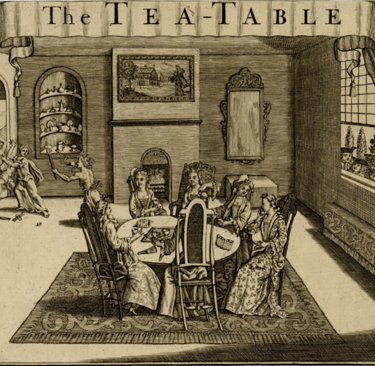

As men saw it, women behaved differently when they gathered around a tea table. In the art and literature of the period, tea-drinking was associated with gossip: ‘The Tea Table’, a print published in London earlier in the century, shows men outside the room, peering into a female space. Six women are sharing tea and scurrilous stories. On the table is a book entitled ‘Chit Chat’ and the text reads, in part – ‘Ever there we see, Thick Scandal circulate with right Bohea. . . At each Sip a Lady’s Honour Dies’.

The 'Lady Juliana' in 1782

('The Lady Juliana in tow of the Pallas Frigate, The Sailors Fishing the Main Mast which was Shatterd by Lightning', aquatint by John Harris after Robert Dodd, n.d., c. 1800, UK National Maritime Museum, PAH 8432)

Female Space on Convict Ships

On the Lady Juliana, water was boiled for the women morning and night. On the ill-fated Neptune, they were permitted to go down into the galley and make tea whenever the weather permitted. In later years, the women's messes were supplied with tea kettles, and by the 1820s, their quarters were fitted with shelves where they could 'stow their tea ware'.

The women of the Lady Juliana were not gathering around a mahogany table or drinking from fine china, but their petition for tea amounted to a request that they be allowed to construct female spaces within the otherwise male environment of a convict transport. This was the gift of Richard Alley and William Richards to them and to every woman who sailed in a convict ship thereafter.

____________

[1] Alley to Richards, 31 March 1789, UK National Archives (hereafter TNA) T1/667/400.

[2] Saunders’s Newsletter, 9 February 1784; Norman Scarfe (ed.), A Frenchman’s Year in Suffolk, 1784, Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1988, p. 18; Pim de Zwart and Jan Luiten van Zanden, The Origins of Globalization, Cambridge University Press, 2018, p. 249

[3] Sir Frederick Morton Eden, The State of the Poor, Volume 1, (1797), London: Frank Cass & Co Ltd, 1966, p. 535.

[4] David Porter, The Chinese Taste in Eighteenth-Century England, Cambridge University Press, 2010, pp. 139 & 141.

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.