Sydney's 'Natural Quays'

Sydney Cove was selected as the site for European settlement, in part because of its natural rock platforms and deep water, which allowed for the easy loading and unloading people and cargos.

Gary L. Sturgess

7/6/20257 min read

Selecting Sydney Cove

In his first letter from the newly established colony, Governor Arthur Phillip explained to the Home Secretary why he had selected Sydney Cove as the site for the settlement:

‘I fixed on the [cove] that had the best spring of water, and in which the ships can anchor so close to the shore that at very small expence quays may be made at which the largest ships may unload.’ [2]

Note that he didn’t say that it had a wonderful stream of water – as they would soon discover, the stream (later known as the Tank Stream) slowed to a trickle during a dry – just that it was the best of the inlets he had explored.

And he did not extol the virtues of the white sandy beach at the southern end of the cove: what attracted him was that just off shore there was deep water, with rock platforms that almost might have been shaped by engineers. On his return to Botany Bay from that first exploration of Port Jackson, Phillip called the officers of the fleet together, and explained that the harbour had:

‘. . . many rock eminences, quite perpendicular & perfectly flat at top wh. will answer every purpose of load'g and unload'g the Largest Ships equally the same as if made by the most expert workmen. . .’. [3]

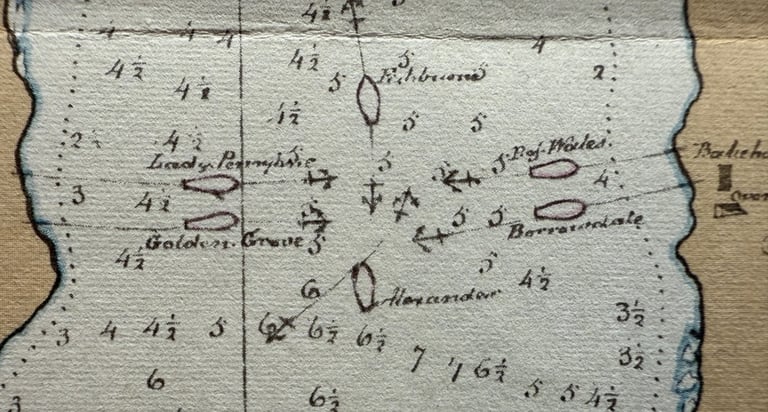

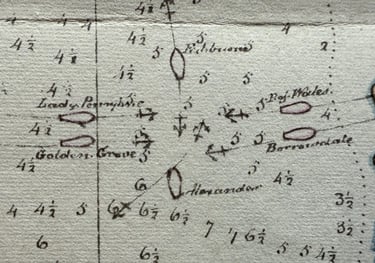

William Bradley, 1st Lieutenant of the flagship, HMS Sirius, also wrote about the selection of this cove in his personal version of the ship’s log, noting that the transports could:

‘. . . anchor near enough to moor with a shorefast in very good depth of water, from 6 to 5, 4 & 3 close alongside of the rocks.’ [4]

Indeed, when the fleet warped in the cove early on the morning of 27 January 1788, that is precisely what four of the ships did, as Bradley’s accompanying chart shows:

That evening, one of the surgeons wrote:

‘The Ships some of them lay so near the Stone cliffs that you may wh ease jump from the Ship on Shore. . . The Water here even to the very side of the shore is 5 & 6 Fathoms & exactly like a Canal in a Garden, you may wh ease fasten the Ships to the trees instead of putting down the Anchor.’ [6]

Boats were used to carry the people and provisions ashore, transporting them to the rock platforms along the western side, where they could be unloaded directly onto dry land. But some of the crew took advantage of the proximity to land in other ways: several weeks after their arrival, the cook of the Prince of Wales was drowned as he was making his way ashore by shimmying along the hawser, having fallen into the water when two boys rocked the rope as a joke. [7]

Later Impressions

A wharf was erected on the western side in 1791, which came to be known as the public wharf (because that was where people and cargoes were generally brought ashore) or Hospital Wharf (because it was located in front of the hospital), and later as King’s Wharf. A second one built on the eastern side of the stream, largely reserved for official use and known as the Governor’s Wharf.

But in the decades that followed, ships would continue to moor further along the cove, close to the shore. Thus, when the Britannia arrived in Sydney Cove in June 1794, with stores Captain Raven had purchased at Batavia, she was ‘moored to the trees ashore’. [8]

In May 1802, the commander of the French explorer, Naturaliste, which was visiting the settlement, noted that a large ship could come within two cables length of the Governor’s Wharf, ‘and even berth along the shore in other parts of the cove’. [9]

And when two Russian ships, the Blagonamerennyi (Good Intent) and the Otkrytie (Discovery), visited Sydney Cove in March 1820, one of the logs recorded that they moored so close to the rocks on the western side that they could walk ashore across planks:

‘At length, we sighted Sydney proper in a narrow inlet, and there we let go anchor, right by Captain Piper’s house. We moored so that gangplanks could be run out: we could plainly hear everything that was said in the Captain’s dwelling! We were standing in six fathoms of water, mud bottom.’ [10]

A Sydney resident wrote of these years, that ‘the Sydney Wharf was the natural rocks’. [11] Sydney Cove was internationally renowned for these rock platforms which suddenly shelved into deep water. [12] A gazetteer published in London in 1798 advised visiting mariners that the cove was:

‘perfectly secure from all winds; and for a considerable way on both sides, ships can lie close to the shore; nor are there any rocks or shallows to render the navigation dangerous.’ [13]

And François Peron, the commander of the 1802 French expedition:

‘The natural quays are so perpendicular and well formed that, without any kind of labour or expense on the part of the English, the largest ships might be laid along them with perfect security.’ [14]

In 1804, James Thomson, who had been Assistant Surgeon in the colony for some years, described ‘a beautiful basin of water’ where ships could anchor ‘within three feet of shore (if they please)’. [15] And writing in the 1840s about his arrival in the settlement two decades before, an anonymous author dubbed ‘An Emigrant Mechanic’ observed:

‘One of the excellences of the site of Sydney is that either deep water washes the rock on which it is built, or, where it does not, a good depth can with very little difficulty be artificially obtained by a short jetty’. [16]

Siltation and a Semi-Circular Quay

By the 1830s, this was no longer true. Clearing the vegetation for the roads and houses had caused a great deal of sand and filth to wash down the Tank Stream, and the water was noticeably shallower at the southern end of the cove. In September 1836, a committee chaired by the Chief Justice, James Dowling, recommended to the Governor that a semi-circular quay be erected out across the southern end, which would enable around 30 ordinary sized merchantmen to load and unload at one time. Dredging would still be required to take away the detritus that would continue to wash into the cove, but the key to the siltation problem lay in sealed streets and effective drainage. [17]

Soil was already building up along the western shore as far as Campbell’s Wharf, but no steps were taken to address the problem at this time. The eastern side of the cove was not as badly polluted. [18]

A ‘Waterman’s Wharf’ was erected on the western side between Campbell’s Wharf and Cadman’s Wharf in 1841, but it serviced boats and other small vessels, and the depth of the water was not important.

William Bradley, ‘Sydney Cove, Port Jackson’, detail showing ships moored to trees on shore. [5]

Jacob William Jones, ‘View of Sydney Cove’, showing the Waterman’s Wharf in 1845 [19]

But by 1854, planning was underway for the construction of a timber wharf which would run along the western side, extending 40 feet out into the water. From a series of soundings, the engineers established that the underlying rock was, on average, 25 feet below the high-water mark. At the deepest, it was 35 feet below high water. [20]

Frederick Garling, ‘Sydney Cove from Dawes Point’, showing the flat rock platforms in the cove [1]

Ships moored along the western side of the quay in 1871, ML SPF/781 [21]

The depth of the water along the western side of the cove is evident today from the cruise ships which moor at the Overseas Passenger Terminal, the largest of which have a draught of eight and a half metres (or 28 feet).

_________________

[1] Frederick Garling, ‘Sydney Cove from Dawes Point’,1839, Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW (hereafter SLNSW) DG SV1/47

[2] Phillip to Sydney, 15 May 1788, Historical Records of NSW (hereafter HRNSW), Vol. 1:2, p. 122

[3] Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘Journal of Arthur Bowes Smyth, 22 March 1787 to 8 August 1789’, National Library of Australia MS4568, 23 January 1788

[4] William Bradley, ‘Journal of HMS Sirius, 1787-1792’, Australian National Maritime Museum, 00055232, p. 207

[5] William Bradley, ‘Sydney Cove, Port Jackson’ (detail), SLNSW, Safe 1/14

[6] Arthur Bowes Smyth, ibid., 26 January 1788. In spite of the date in Smyth’s diary, this entry was clearly made on the 27th

[7] Arthur Bowes Smyth, ibid., 16 February 1788

[8] Robert Murray, ‘Journal of a Voyage from England to Port Jackson, New So Wales. . .in the Ship Britannia, Mr W. Raven Commr, by Rt Murray, 16 February 1792 to 3 March 1795’, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts, Log 26, Microfilm 56 Reel 215, 1 June 1794.

[9] Jacques-Félix-Emmanuel Hamelin, ‘Journal’, Archives Nationale de France, Paris, série Marine, 5JJ41-42, entry for 28-29 Floreal Year 10 [18-19 May 1802], published in Jean Fornasiero and John West-Sooby, French Designs on Colonial New South Wales, Adelaide: Friends of the State Library of South Australia, 2014, p.337.

[10] Al. P. Lazarev, Zapiski o plavanii voennogo shliupa 'Blagonamerennogo . . (Notes on the Voyage of the Sloop-of-War ‘Blagonamerennyi’. . .), Moscow: Geografgiz, 1950, translated and published in Glynn Barratt, The Russians and Australia, Vol. 1, University of British Columbia Press, 1988, p. 150

[11] Sydney Herald, 13 May 1826, p. 2

[12] A.N., ‘Hove Down at Mosman’, Evening News, 26 March 1910, p. 3

[13] Clement Cruttwell, The New Universal Gazetteer or Geographical Dictionary, London, 1798, Vol. 3, entry for ‘Sydney Cove’.

[14] Francois Peron, A Voyage of Discovery to the Southern Hemisphere, London: Richard Phillips, 1809, Chapter 20.

[15] Thomson to Cooke, 28 June 1804, HRNSW Vol. 5, pp. 387-391, at p. 390

[16] ‘An Emigrant Mechanic’, Settlers and Convicts, London: C. Cox, 1847, p. 15

[17] ‘Circular Quay at the Head of Sydney Cove’, Commercial Journal and Advertiser, 28 September 1836, p. 4

[18] Report of Captain Barney of the Royal Engineers, 16 July 1836, published in ‘Circular Wharf’, The Australian, 16 September 1836, p. 2

[19] Jacob William Jones, ‘View of Sydney Cove’, 1845, Mitchell Library (hereafter ML), SLNSW DGA32

[20] Sydney Morning Herald, 5 September 1854, p. 5

[21] ‘Ship Sobraon, Circular Quay, Sydney, N.S.W’, 1871, ML SLNSW SPF/781

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.