Sydney’s Early Fishing Community

Shortly after the British came ashore in late January 1788, a fishing community was established in Sydney Cove, from which a six-oared cutter would venture out each night to haul the seine net.

Gary L. Sturgess

5/9/202414 min read

Through a close reading of the sources, it is possible to identify the location of this community, and reconstruct events involving the convict fishermen, including the escape by a number of them in March 1791.

Sydney’s Early Fishermen

A fishing community was established in Sydney Cove shortly after the European settlers first came ashore in late January 1788, with a convict gang sent out each night to haul the seine, in the hope of supplementing the dried and salted rations brought out from England.

They were under the supervision of William Bryant, a convict from Cornwall who had been ‘bred from his youth to the business of a fisherman’ and came to be known in the colony as ‘the fisherman’.[1] Bryant was one of the convict overseers who married at the first opportunity, on the 10th of February 1788: he was probably under pressure from the Governor to set an example, but he had already formed a relationship with Mary Braund, the woman he married, while they were being held on a hulk at Plymouth prior to sailing.

So valuable was the fisherman to the well-being of the settlement that a hut was built for him and his family, and he was allowed to keep a proportion of the catch for his own consumption. When in February 1789 it was found that he had been taking significantly more than his share, he was removed from this position of trust and from the hut, but quickly reinstated when he proved to be indispensable.

We have little information about the other members of his crew, but they included a former seaman, a man transported for stealing a sloop, two men from Wapping who were thus ‘used to the sea’, and a London waterman. The boat was a six-oared cutter, English-built and thus probably from the Sirius, which Bryant kept in excellent order.

Fishing

It is unknown when Bryant’s fishing crew was established. Many of the references to fishing throughout 1788 relate to the ships’ crews who were going out in boats to haul the seine to meet their own needs, and the Governor periodically sent his boat out to catch fish for the people living at Government House.

But it seems likely that Phillip was referring to the boat under Bryant’s command when he wrote to the Home Secretary in May 1788: ‘Some days great quantities are caught, but never sufficient to save any part of the provisions; and at times fish are scarce’.[2] At times, vast quantities were caught, and the haul was limited by the number of boats at their disposal. But throughout the winter, the fish remained elusive, only coming back to the coves and bays when the warm weather returned in September.

When the Sirius was wrecked at Norfolk Island in March 1790 and the settlements was faced with the prospect of starvation, every boat in the colony, public and private, was employed in fishing, with the catch shared across the whole community. Bryant’s expertise must have been of great value in this period, although for a time, he and his crew also came under much closer supervision.

There is no description of how Bryant and his crew worked, but the following account, given by one of the men in the Governor’s boat, provides us with some idea of their routine:

Our customary method was to leave Sidney Cove about four a’clock in the after noon and go down the harbour and fish all night from one cove to another. We have made twenty three halls of seene in one night and not ketch as many as would fill a bucket, and other times, in one or two halls, falling in with schools, that would be sufficient to fill our stern sheets. We then would make a fier on the beach, cook our supper, and take our grog, lay down in the sand before the fire, wet or dry, and go to sleep till morning, when we would be often disturbed by the natives heaving there spears at us at a distance, and being in the night, it would be by random. In the morning we would return, take the fish to the Governers house, where they would be sheared out as far as they would go.[3]

The Bryants’ hut and another building probably used to house the fishing gear and some members of the crew, had been completed by August 1788 (on which, see below), and throughout the summer, Bryant employed a man to cultivate his garden, paying him with fish.

By way of encouragement, the fishermen were permitted to keep some of the catch, but this was not enough: by December 1788, Bryant was operating a black market, selling fish to the assistant commissary and some of the marines’ wives. Several of his men were also caught up in this illicit trade, supplying blackfish, flathead and light horsemen (snapper) in return for spirits, pork and flour. Bryant also earned money (or money’s worth) by making seine nets for the officers and gentlemen, and selling old rope for use in thatching houses.

The Fisherman’s Hut

By December 1788 at the latest, Bryant’s hut was known throughout the settlement as ‘the fisherman’s hut’. It must have been located close to the water, and we know that it lay at the edge of the settlement, since it is described in one account as being close to the woods. Given that the fishermen often went out at night and returned in the early hours of the morning, it made sense for them to be housed away from the main settlement.

When Bryant and his family escaped in the fishing boat in March 1791, it was said that he had secretly made his way with stores and provisions from his hut to ‘the point’. These articles could not be loaded into the boat in full view of the settlement, so it was moored around one of the points which lined the cove, close enough to the Bryants’ hut that the escapees could not be seen.

Evidence given by one of the fishermen in Bryant’s trial in 1789, establishes that the hut lay on the eastern side of the stream which divided the settlement (later known as the Tank Stream, which ran along the western side of what is now lower Pitt Street). Joseph Paget testified that he had delivered fish to one of the marine wives in ‘the camp’, for which he was given a pint of liquor, ‘which he brought over to Bryant’. Since court cases were held in the Judge Advocate’s house, located close to Government House on the east side, this means that the fisherman’s hut was located on that side. Paget also testified that Bryant sent him over to Mr Clark, ‘the victualler’, and that he returned with a bottle of rum, payment for a large flat-headed fish. Zachariah Clark was the assistant commissary and his hut was located close to the storehouses, which lay at the heart of the settlement on the west-side, not far from the marine camp.[4]

There can be no question, then, that the Bryants’ hut lay on the eastern side of the settlement, and it was located close to the water and the bush. The only place which meets this description would be a site on the far side of the Governor’s garden, part way along the point then known by its indigenous name, Tubowgule (and today known as Bennelong Point, named after the first Aboriginal man to build a close relationship with the intruders).

Turning to the early maps and drawings, we find that from an early date, there were two houses at the north-east end of the Governor’s garden, sometimes shown with a large boat anchored in front. It seems likely that these are the fisherman’s hut and a second building also used by them.

William Dawes’ plan of the settlement, drawn in May and June 1788, shows a ship or boat anchored close to the shore on the eastern side of the cove, at the north-east end of the Governor’s garden, however this might represent one of the transports being hauled down for cleaning prior to sailing. No buildings are shown on shore, and while Dawes’ plan is far from complete, it is possible that the Bryants’ hut was not yet finished.[5]

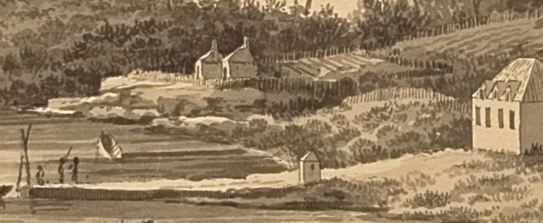

The earliest known portrayal of these buildings is Dayes’ engraving of John Hunter’s sketch of the cove dated to August 1788 (below). Bennelong Point lies to the left in this detail from the engraving, the Governor’s fenced garden to the right. The ship in the foreground is one of the First Fleet transports being hauled down, probably the Golden Grove.

Sydney Cove was then V-shaped, so it is difficult to establish precisely where the huts were located. The cove did not acquire its current U-shape until the ‘semi-circular quay‘ was erected in the mid-19th century, but given the likely extent of the Governor’s garden, it was probably located near what is now the eastern end of today’s Circular Quay.

There are no maps or drawings of the eastern side of the cove dating from 1789 or 1790, and the next known image is from a painting made by George Raper, a midshipman on the Sirius, on his return from Norfolk Island in February 1791. This shows the proximity of these two huts to the Governor’s garden, and their closeness to the woods. Raper also has a large boat anchored just offshore.

Their first appearance in a map of the settlement can be dated no more precisely than 1792. The huts appear at the top of the detail from this map published below. The large block of land marked K is the Governor’s garden, and the thin protrusion at the bottom left is the Governor’s wharf.

From 1792, the huts appear in a number of sketches and drawings. The following, for example, is a detail from one of Brambila’s drawings of the settlement in early 1793, looking north-east from the ridge on the west side across the Governor’s wharf. It would appear that Bennelong Point (to the left of the cottages) was still covered with trees and scrub at this stage.

Identifying these huts helps us to make sense of a number of events in the early years of the colony which involved the fishermen.

Bryant’s trial

Bryant was brought before the magistrates on the 4th of February 1789 and convicted of selling fish to the settlers in breach of his orders. He had been over at bakehouse one morning shortly before Christmas when he instructed Joseph Paget to go over to his (Bryant’s) hut, collect ten blackfish from the bedroom and bring them ‘privately’ through the woods. They met on the bridge which had been recently erected across the stream (in what is now Bridge Street), and Bryant told Paget where the fish were to be taken, and how much he would be paid.[10]

Once we understand the location of the bakehouse, Bryant’s hut and the bridge, these movements are logical and easy to follow.

Relations with Aboriginal Groups

Relationships between the fishermen and the Aboriginal peoples of the region had been complicated since their first encounters in Botany Bay in January 1788. The fishermen were under instruction to share their catch, and from time to time, Aboriginal men would even assist in hauling the nets.

Richard Williams, second mate of the Borrowdale, one of the First Fleet storeships, described a friendly encounter with a small Aboriginal group in the lower harbour in late April 1788:

On Sunday the 27th, went down the river, having the charge of our small boats, with 8 convicts, who went to fish ashore. We put into a bay about two miles and a half from where the ships lay, and spoke with some of the natives, (men) who had three children with them, one of which was an infant, whom I took in my arms.[11]

But tensions arose whenever the fish were scarce, and it would be unsurprising if there was not concern among the ancient custodians of the harbour about the sustainability of such large catches.

In the winter of 1788, twenty armed Aboriginal men came down to a beach where some of the Europeans were working a net and stole a large part of their catch. It is probable that these men were fishing for the Governor and his household, but the risks to Bryant and his gang were heightened. As Phillip explained:

The coxswain had been ordered, however small the quantity he caught, always to give them a part whenever any of them came where he was fishing, and this was the first time they ever attempted to take any by force. While the greatest number were seizing the fish, several stood at a small distance with their spears poised ready to throw them if any resistance had been made, but the coxswain very prudently permitted them to take what they chose, and parted good friends.

They, at present, find it very difficult to support themselves. In consequence of what happened yesterday, no boat will in future go down the harbour without an officer.[12]

When the fish returned in September, spears were also thrown at ‘the people in the fishing boat’, almost certainly a reference to Bryant and his men.[13] Tensions eased in the new year after smallpox swept through the Aboriginal camps, and a large number of them died or scattered abroad.

It would be surprising if Bryant did not try to build trust with the people around the harbour, but there is only one known incident which hints at these relationships. In late February 1791, as the fishermen were returning to the cove with a full load of fish, the cutter was overturned in a squall.

In the boat with Bryant was Bennillong's sister and three children, who all got safe on shore, the woman swimming to the nearest point with the youngest child upon her shoulders. Several of the natives, on perceiving the accident, paddled off in their canoes, and were of great service in saving the oars, mast, etc. and in towing the boat up to the cove.[14]

The Governor wrote that without the assistance of these men, one of the fishing crew would almost certainly have drowned. Marine Captain Watkin Tench said that Bennelong and some other men who had seen the accident, immediately dived into the water ‘and saved all the people’: ‘When they had brought them on shore, they undressed them, kindled a fire and dried their clothes, gave them fish to eat and conducted them to Sydney’. They also collected the oars and the fishing equipment scattered around the shore and returned them to the camp. Bennelong had been out of favour with the Governor for some time, and as a result of these actions, Phillip allowed him to have access to Government House once more.[15]

Bennelong had made an unofficial claim on Tubowgule. He had lived at Government House when he was first captured in November 1789, but there are several sources which indicate that Phillip had a hut built for him and his keeper on the eastern point of the cove. It is unlikely that he ever took up residence, since his escape in the early hours of the morning one day in April 1790 was from an upstairs room at Government House.

But when he began to visit the camp again from October of that year, Bennelong asked the Governor to have a hut built for him at the end of Tubowgule. Phillip readily agreed, and a brick house, 12 feet square and covered with tiles, was completed several weeks later. It seems likely that Bennelong is the reason Tubowgule retained (or regained) its indigenous name, for several years at least, the only part of the cove to do so. This means that Bennelong and the Aboriginal people who came to stay at the hut were the fishermen’s only neighbours on the northern side.

Bennelong robbed several of the private boats of their fish in December 1790, ‘threatening the people, who were unarmed, that in case they resisted he would spear them’.[16] There are no reports of a similar attack on Bryant’s boat, and it is surely significant that some of Bennelong’s family were in the boat as it was making its way back to the cove in February 1791.

It is also noteworthy that the Sydney people had a term for ‘where the fisherman's hut was’ – ‘darangaraguya tarrangera guy’ – which means that the site had meaning for Aboriginal visitors to the cove, possibly because they could obtain fish there.[17]

The following drawing from 1792 shows Bennelong’s hut at the very end of the point and the fishermen’s huts immediately to the right of the ship.

The Escape

On the night of the 28th of March 1791, William and Mary Bryant and their two children escaped in the fishing boat, accompanied by seven other men. They made their way up the east coast of Australia to Kupang in West Timor, where they were arrested and taken to Batavia. William and one of the children died there of a fever, but Mary made her way home, to become a national celebrity.

Bryant was the mastermind. He had been quietly making preparations for months, buying a compass, a quadrant and nautical charts, muskets, powder and shot, and bags of rice from the master of the Waaksaamheyd, a Dutch merchantman which had brought much-needed supplies to the colony from Batavia, as well as flour from Robert Sideway, the convict baker. They also took carpenter’s tools and a new seine net which Bryant had made for one of the officers.

On the night of the escape, they rowed the cutter out of the cove, as they had done hundreds of times before to go fishing, and moored it on the outer side of the east point. They then made their way back through the scrub to the hut to collect Bryant’s family, the food supplies and the navigation instruments. This was only possible because the fishermen’s huts were located so close to the bush.

A number of the men had partners, but they kept their departure a secret even from them. The only people who might have given them away were Bennelong or one of the Aboriginals visiting his hut. But no one noticed that they were missing until the next morning when they did not return from fishing, and by then, they were well outside the heads.

The Governor and his officers had known for some weeks that Bryant was talking about escape, but they had no idea how advanced his plans were, and they were obviously reluctant to release him from his position. As a result of the escape, regulations were introduced limiting the size of boats which could be built in the colony, and thereafter, a much closer eye was kept on the fishermen.

_____________

[1] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [1798], Sydney: A.H. & A.W. Reed, 1975, Vol. 1, p. 44.

[2] Phillip to Sydney, 15 May 1788, Historical Records of Australia (hereafter HRA), Series 1, Vol. 1:22.

[3] John C. Dann (ed.), The Nagle Journal: A Diary of the Life of Jacob Nagle, Sailor, from the Year 1775 to 1841, New York: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1988, p. 96

[4] R v Bryant, 5 February 1789, ‘Bench of Magistrates Sydney, Minutes and Proceedings, 19 Feb. 1788 to Jan. 1792’, State Archives of NSW, SZ765, pp. 138-139.

[5] [William Dawes], ‘Sketch of Sydney Cove, Port Jackson’, [May-June 1788], original at the UK National Archives (hereafter TNA), MPG 1/300. The map was transmitted to England with Philip to Sydney, 9 July 1788, TNA CO201/3/46a-47.

[6] ‘Drawn by E. Dayes from a Sketch of J. Hunter. View of the Settlement on Sydney Cove, Port Jackson, 20th August, 1788. Publish’d Oct. 18th 1792 by J. Stockdale Piccadilly’.

[7] ‘View of the East Side of Sidney Cove, Port Jackson. . .’, Paper Drawing No. 16, Natural History Museum (hereafter NHM), London.

[8] ‘A Survey of the Settlement in New South Wales’, with note by Arthur Phillip dated 2 December 1792, State Archives of NSW, SZ430.

[9] Fernando Brambila, ‘Vista de Colonia Inglesa de Sydney en la Nueva Gales Meridional‘, British Library, George III, Kings Topographical Collection, K. Top. 124, Supp. 43.

[10] David Collins, ‘An Account of the English Colony. . .’, op. cit., Vol. 1, pp. 44-45.

[11] ‘Extract of a Journal from England to Botany Bay by Richard Williams. . .’, Broadsheet, 1789, State Library of NSW, DSM/Q991/W

[12] Phillip to Nepean., 10 July 1788, HRA, Series 1, Vol. 1, pp. 66-67.

[13] David Collins, ‘An Account of the English Colony. . .’, op. cit.,Vol. 1, p. 30.

[14] Ibid., pp. 126-127.

[15] John Hunter, An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson. . . and the Voyages, London: John Stockdale, 1793, pp. 509-510; Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, London: G. Nicol, 1793, p. 133.

[16] Watkin Tench, op. cit., p. 104.

[17] Unknown [David Collins and Arthur Phillip], ‘Vocabulary of the Language of N.S. Wales in the Neighbourhood of Sydney’, School of Overseas and African Studies, London, Marsden Collection, Library Special Collections, pp. 54-55.

[18] ‘Port Jackson Painter’, ‘A Partial View of Sydney Cove taken from the Sea side before the Surgeon Generals House’, NHM, Watling Drawing, No. 14.

Detail of Edward Dayes (eng.), ‘View of the Settlement on Sydney Cove, Port Jackson, 20th August, 1788’, from a sketch by John Hunter.[6]

Detail of George Raper, ‘View of the East Side of Sidney Cove, Port Jackson’, [Feb-Mar 1791].[7]

Detail of Unknown, ‘A Survey of the Settlement in New South Wales’ [1792].[8]

Detail of Fernando Brambila, ‘Vista de Colonia Inglesa de Sydney. . .’, [March-April 1793].[9]

Detail of Unknown, ‘A Partial View of Sydney Cove. . .’, [c.1792][18]

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.