Sweet Tea

From shortly after the first Europeans landed in Sydney Cove in January 1788, a local herb was used to make an infusion known locally as sweet tea, which tasted of licorice. In the early years of the settlement, the convicts would risk their lives to go out into the woods to collect it.

Gary L. Sturgess

4/20/20254 min read

One of the things that the First Fleet convicts missed most about England was their tea, as someone wrote by the last of the returning transports:

'As for the distresses of the women they are past description, as they are deprived of tea and other things they were indulged in, in the voyage, by the seamen. . .' [1]

Within months (and probably within a matter of weeks), they were drinking a brew made from the leaves of a local vine, which tasted like sarsaparilla. The first mention of this plant is May 1788, when a convict who was convalescing at the hospital was speared whilst out in the woods gathering herbs to make tea. Many kept a supply in their tents, and with time some would grow the vine in the gardens surrounding their huts. By June 1788, at the latest, it had acquired the name ‘sweet tea’.

This plant seems to have been relatively common, although at some distance from the camp. In the 1870s, a resident of Sydney recalled that 30 years before, he had gathered the ‘native tea’ in several places around the harbour. It could be found:

'. . . on the shores of the harbour in spots, say from the Pig Tree in the Domain to Lady Macquarie's Chair between the road and the water, among the rocks and brushwood. I have never seen it far back from salt water, neither inland in any of the colonies . . . I never found any on the western slopes of the harbour, always on the cliffs facing east.' [2]

The surgeon general, John White, classified this plant as Smilax glyciphylla: in later years, it would be known by a variety of names - ‘native tea’, ‘sweet sarsaparilla’, ‘wild sarsaparilla’ and ‘wild liquorice’ – but it was always known to the common folk of Sydney as ‘sweet tea’.

It is a climbing vine which can grow to eight metres in length. It has a licorice taste and for the most part, it was drunk as an infusion made from the leaves, although the root and the berry might also be used.

From the First Fleet onwards, it was thought to be an anti-scorbutic, and it was used for the treatment of colds and catarrh. It was long employed as a cure-all, for ‘cleansing the blood’ and as a general pick-me-up. John Nicol, the steward on the Lady Juliana (1789) recalled a story told about an old First Fleet convict:

'. . . her hair quite grey with age, her face shrivelled, who was suckling a child she had born in the colony. Every one went to see her, and I among the rest. It was a strange sight, her hair was quite white. Her fecundity was ascribed to the sweet tea.' [3]

Because of its abundance around the harbour and along the adjoining coast, sweet tea was a Sydney tradition, and the vine continued to be collected and sold at Paddy’s Market as late as the First World War. Over the years, various entrepreneurs produced a tonic from it, and at one point in the mid-19th century, the syrup was exported overseas.

But the first exports were in July 1788, when one of the convicts sent several of the leaves home as a sample. John Nicol collected two bagsful, as presents for his friends in England:

'. . .but two of our men became very ill of the scurvy, and I allowed them the use of it, which soon cured them, but reduced my store. When we came to China, I showed it to my Chinese friends, and they bought it with avidity, and importuned me for it, and a quantity of the seed I had likewise preserved. I let them have the seed, and only brought a small quantity of the herb to England.' [4]

Collecting the leaves, for sale or for personal use, required the convicts to venture out into the woods, and throughout the First Fleet period, several of them were killed or wounded by the indigenous peoples of the Sydney basin. Two of the marines on a foraging expedition at Rose Hill (Parramatta) also went missing in 1789.

It was supplied for the sick and dying convicts of the Second Fleet when they arrived in June of 1790, and when the Neptune sailed from NSW in August of that year, one of the crew of the Sirius who sailed with her as a working seaman, took some of the leaves. He later claimed that they had saved him in the face of the inadequate provisions supplied by the captain.

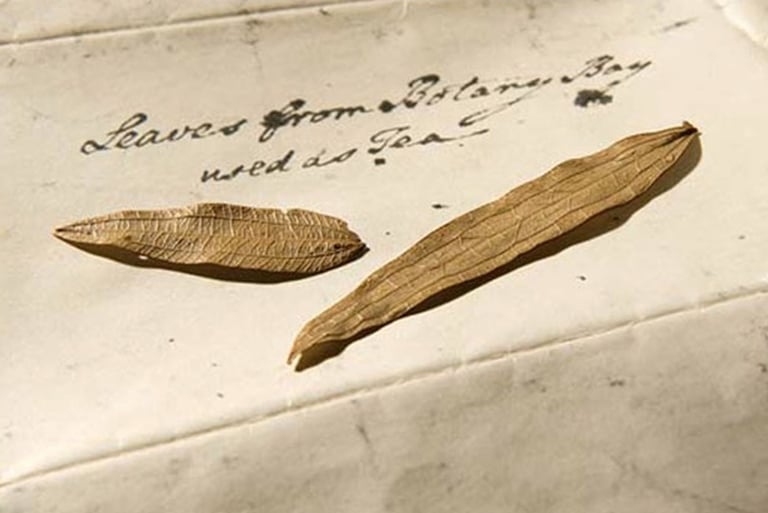

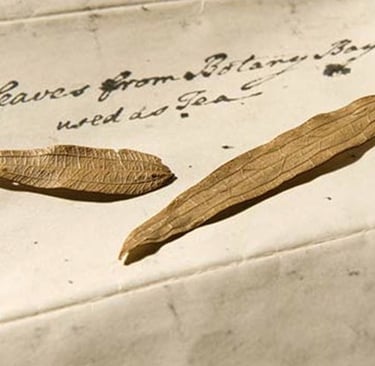

When the Bryant party escaped from the colony in the fishing boat in March 1791, they also took bags of leaves with them, some of which were taken to London and wound up in the possession of James Boswell, the author who served as the public face of a campaign seeking a pardon for Mary Bryant. Two of the Bryant leaves are today held by the State Library of NSW.

Leaves and berry of the sweet tea

It has not yet been established whether there was sufficient Vitamin C in sweet tea for it to serve as an anti-scorbutic, but it is clear that from as early as 1790, it was being purchased by the masters of visiting ships in an attempt to expedite the recovery of their crews. Much of whatever Vitamin C the leaves contained was probably destroyed when they were steeped in boiling water. Recent research has shown that the ‘native tea’ is an antioxidant, with possible benefits in helping to prevent cardio-vascular disease and cancer. [5]

_____________________

[1] A letter from Port Jackson, said to have been written 'by a female pen', 14 November 1788, London Chronicle, 28-30 May 1789.

[2] Australian Town and Country Journal, 28 September 1878, p.17

[3] John Nicol, The Life and Adventures of John Nicol, Mariner, London: Cassell & Company, 1937, p.142.

[4] John Nicol, Life and Adventures, pp.142-143.

[5] Sean D. Cox and Julie L. Markham, ‘Smilax glyciphylla, the Australian native sarsaparilla’, Aust. J. Med. Herbalism, (2003) 15 (1), pp.5-8.

Sweet Tea leaves from the Bryant party now in the Mitchell Library in Sydney, SLNSW R807

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.