Sunday Morning Coming Down

Until recent decades, people often dressed in their best clothes on Sundays, even if they were not going to church, and Sunday dinner was the highlight of the week. And that was true on convict ships, too.

Gary L. Sturgess

10/22/20244 min read

With the recent passing of Kris Kristopherson, I was listening to his first hit (as a song writer), ‘Sunday Morning Coming Down’. How many people these days understand why he fumbled through his closet to find his ‘cleanest dirty shirt’, when he had no intention of going to church? And why the Sunday smell of someone cooking chicken?

Until the past few decades, people often dressed in their best clothes on Sundays, even if they were not going to church, and Sunday dinner was a special family meal. In Two Years Before the Mast, the great source about daily life on sailing ships, Richard Henry Dana explained that Sundays were special at sea, too:

‘The decks are washed down, the rigging coiled up, and everything put in order; and throughout the day, only one watch is kept on deck at a time. The men are all dressed in their best white duck trowsers, and red or checked shirts, and have nothing to do but make the necessary changes in the sails. They employ themselves in reading, talking, smoking, and mending their clothes. If the weather is pleasant, they bring their work and their books upon deck, and sit down upon the forecastle and windlass. This is the only day on which these privileges are allowed them. . .

To enhance the value of the Sabbath to the crew, they are allowed on that day a pudding, or, as it is called, a ’duff’. This is nothing more than flour boiled with water, and eaten with molasses. It is very heavy, dark and clammy, yet it is looked upon as a luxury. . .’[1]

This was true on convict ships as well, although as usual, the evidence has to be brought together from a variety of sources. On the Speedy (1799), the wife of the Governor-elect, Philip Gidley King, wrote about one particular Sunday at sea, where the ladies (as she called them) were all ‘dressed out very neat’.[2] By the 1820s, at least, two days a week were set aside for the men to be shaved, one of which was Saturday, and on Sunday morning they were required to bathe and then be mustered in their clean clothes ahead of ‘divine service’.

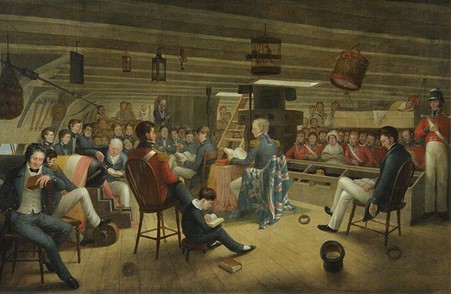

When it was held on convict ships, the divine service took place on the quarter deck. The paucity of detailed records means that we do not know how common it was, but prayer services were occasionally held on the First Fleet transports, and there is evidence of them being conducted on two ships which carried out convicts in 1792. Of the other three transports where it is known that preaching and/or prayers were routinely held throughout the voyage, two were carrying ministers or missionaries. In truth, we do not know how common it was, but more so in the later years of the transportation system.

Unless there was a chaplain on board, divine service was not often conducted on naval ships in this period, although this changed with the rising influence of the Evangelicals in the late 18th century. There is no evidence of prayers being held on HMS Sirius, the flagship of Australia’s First Fleet, although the commanders of HMS Guardian and HMS Gorgon, two naval vessels which sailed out with stores and convicts in 1789 and 1791 respectively, usually did. This was not because of an aversion to religion on Arthur Phillip’s part, since on the first Saturday the settlers were on shore in Sydney Cove, the Governor-elect issued a General Order instructing the convicts to assemble the next morning when the Church Drum beat at 10 am: ‘they are Expected to Appear as Clean As Circumstances Will Admit of’.

While the seamen might only have ‘duff’ on Sundays, the convicts enjoyed suet pudding with plums or raisins three times a week, and Sunday was one of these days. John Mellish, a convict sent out in 1811, wrote:

'As to provishions there is not much reason to find fault; on Sunday’s, plumb pudding with suet in it, about a pound to each man, likewise a pound of beef.'[3]

Sailors were often given shore leave on Sundays, and this is evident from the journals of a number of the Botany Baymen which visited New South Wales in this early period. It was also a day when the officers and gentlemen would socialise and dine together. The surgeon on the Minerva, a transport which sailed out in 1799, wrote that the officer commanding the troops spent Sunday in the cuddy with them, accompanied by this wife, ‘and we dined upon a turtle, a pair of ducks, a piece of salt beef and an apple pye’.[4]

The Sunday smell of someone cooking turtle?

____________

[1] Richard Henry Dana, Two Years Before the Mast & Other Voyages, New York: The Library of America, 2005, pp. 20-21.

[2] Anna King, ‘Mrs King’s Journal of Her Second Voyage to New South Wales which commenced on the 20th of November 1799’, State Library of NSW, C185/1, 19 January 1800.

[3] [John Mellish], ‘A Convict’s Recollections of New South Wales’, The London Magazine, (1825), Vol.12, pp.49-67 at pp. 49-50

[4] Pamela Jeanne Fulton (ed.), The Minerva Journal of John Washington Price, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2000, p. 82.

Augustus Earle, ‘Divine Service as it is Usually Performed on Board a British Frigate at Sea’, c.1836 (Royal Museums Greenwich, BCH1119)

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.