Sounds of Early Sydney: Crying Down a Ship's Credit

Residents of early Sydney would have been familiar with the bell and the sonorous voice of the Common Crier, reading out the latest General Orders, or ‘crying down’ crew members of a ship just arrived in port.

Gary L. Sturgess

3/28/20255 min read

In his lecture at the recent colloquium on convict society in Sydney, David Stuart, an historian who specialises in the American merchant ships which visited early New South Wales, presented several pages from the cashbook of the Arthur, an American trader which came into Sydney Cove in 1802 on her way to China.

One of the pages is a list of payments made for goods and services procured during the month she was in port, and among these is a record of 15 shillings paid to ‘the Cryer for Crying down the Ship’s Crew’ – on arrival, the captain had employed the Common Crier (not yet known as the Town Crier) to ‘cry down’ the credit of his crew, a process we do not fully understand.

The Public Crier

The sound of the Public Bellman was familiar to the residents of early Sydney, and one that we are inclined to overlook. This newsletter discusses what we know about these men, and in particular, how they were used by visiting merchant ships.

The earliest mention of a crier (that I have found) is a list of government employees for the year 1797, which includes a bellman at Sydney – but a crier of some kind must have been employed from shortly after the convicts first came ashore in January 1788, since the government needed to know that all of the residents, including those who could not read, understood the latest General Orders. When (for example) in early March 1788, the Governor ordered that any act of cruelty towards the indigenous inhabitants would be dealt with criminally, he would have wanted to know that everyone understood.

The Governor’s official secretary, David Collins, wrote in his journal of orders being ‘given out’, and while he never made clear what this involved, he did write in February 1789

. . . orders, in general, were observed to have very little effect [on the convicts], and to be attended to only while the impression made by hearing them published remained upon the mind. . . [1] (emphasis added)

In his book, The Three Colonies of Australia, published in London in 1852, Samuel Sidney wrote:

A printing-press had been sent out with the first fleet, but no printers; and all public and private announcements were made in manuscript, or by the bellman, until Governor Hunter [in 1795] discovered a printer among his convict subjects, and established a government gazette. [2]

The first evidence of how the bellman was used is to be found in a court case from January 1799, where the magistrates ordered the Common Crier to announce the discovery of two rolls of tobacco in the bush at the edges of the settlement – to give the rightful owner an opportunity to claim them. This was to be done on two consecutive Saturdays, and if no one came forward, they were to be restored to Mrs Mary Mullett, an emancipated convict and trader who said they had been stolen from her.

The qualifications of a Common Crier were listed in an advertisement published some years later in Hobart:

A respectable Man to take the situation of Town Crier. He must be able to read and write, possess a strong clear voice, and be of the most sober and steady habits. [3]

They carried a bell to announce their presence, hence the alternative name ‘bellman’. We have no information about what they wore, but based on the photographs of bellmen from the late 19th century, they would not have worn the pantomime costumes used by ceremonial Town Criers today.

Robert Budd, town crier for Parkes, NSW, 1890s, State Library of NSW

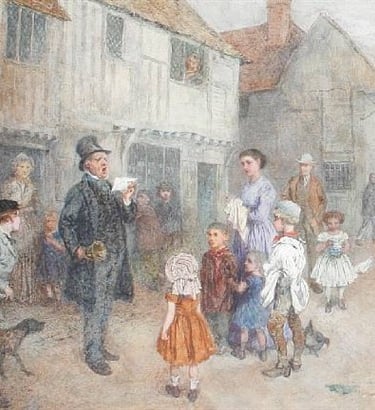

Charles Green, 'The Town Crier, 1867

It was a public appointment, and by the 1820s, there were separate criers for the courts. Other than reading out the General Orders, government might use them (for example) to warn against forged notes circulating in the community. Individuals who had discovered stray animals were legally obliged to use the crier to advertise the fact over several days.

The victims of theft (including stolen notes of hand and bills of exchange) would use them to advertise the missing articles, warning fellow residents against accepting them. Husbands would employ them to warn against credit being extended to spendthrift wives or ex-wives. Mothers would use the Common Crier to notify the public of a lost child. They were engaged by merchants (along with advertisements in the papers and handbills handed out in the street) to promote sales and auctions.

Crying Down the Crew

The first mentions I have found of ‘crying down’ a crew in port orders date to 1802. Shortly before the Arthur arrived in Port Jackson an order was issued: ‘Masters [are] to cry the Credit of their Seamen down, immediately on their arrival’. [4] What this involved was more fully explained in a later set of regulations:

"Masters or Commander of Ships or Vessels are also to furnish the Public Bell-man of Sydney, before the Admission Flag is hoisted on board, with a correct List, under the Signature of such Master of Commander, of the respective Crews on board the said Ships or Vessels respectively, in Order that all Credit to the Ship’s Company may be duly cried down. . ." [5]

This still does not fully explain what was entailed, but a passage in a journal kept by one of the midshipmen on the French expedition, which arrived in April 1802, provides most of the answers. Governor King had decided that since British captains were obliged to cry down the credit of their crew, the French ships should adopt the same precaution. Midshipman Étienne Giraud wrote:

"A poster was read to the crew by which Captain Hamelin warned the inhabitants of the colony that he was not liable for debts that could be incurred by members of his crew." [6]

Clearly, in addition to making public announcements, the bellman had posted notices in the town, warning residents that Captain Hamelin would not be held responsible for the financial dealings of his men.

Masters would also employ the Common Cryer to search out missing crew members prior to sailing. In August 1808, the captain of a visiting ship employed the Public Bellman, Samuel Potter, to cry a Malay boy who was missing from his ship three times, with the promise of a handsome reward.

Over time, government came to rely more on the Sydney Gazette, but public criers would continue to be employed in some Australian towns until the early 20th century.

___________

This Catspaw was updated on 12 July 2025, when I found a reference to the captain of the French ship, the Naturaliste, publishing notices that he would not be liable for the debts of his crew - this was clearly a reference to 'crying down' the credit of the crew, even though it did not mention the bellman.

[1] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, London: T. Cadell, 1798, pp.53-54.

[2] Samuel Sidney, The Three Colonies of Australia, London: Ingram, Cooke & Co, 1852, p.46.

[3] Hobart Town Courier, 26 September 1829, p.3. In fact, the gazette came eight years later.

[4] Port Regulations, 10 October 1802, Historical Records of Australia (hereafter HRA), 1:3, p.713.

[5] Port Regulations, 6 February 1819, Appendix to Commissioner Biggs Report, 1822, UK National Archives, CO201/129.

[6] Port Regulations, April 1804, HRA 1:3, p. 512; Étienne Stanislas Giraud, ’Journal of a Voyage on the Naturaliste’, Archives Nationales de France, Série Marine, 5JJ57, trans. William Land for The Baudin Legacy Project, University of Sydney at baudin.sydney.edu.au/journals/

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.