Sea Provisions ‘Equally Good as When First Put on Board’

I stumbled across an obscure entry in a ship’s journal from 1789 which helps us understand why the provisions on Australia’s First Fleet were so good.

Gary L. Sturgess

6/27/20242 min read

One of the reasons for the outstanding success of Australia’s First Fleet (1787-88) was the high quality of the provisions provided to the convicts and marines throughout the voyage. The Judge Advocate of the new colony, David Collins, wrote:

"...the high health which was apparent in every countenance was to be attributed not only to the refreshments we met with at Rio de Janeiro and the Cape of Good Hope, but to the excellent quality of the provisions with which we were supplied by Mr Richards, Junior, the contractor."[i]

Collins was not alone in commenting on the sea provisions: three other officers and gentlemen mentioned them, and two of these men referred to William Richards by name.

We know almost nothing about how Richards, a small London shipbroker, obtained these provisions: his business records have not survived. But in reading long and wide to get a better understanding of the opening of the Pacific to European trade in the aftermath of the American War of Independence, I came across a fascinating comment in the journal of Captain Nathaniel Portlock, who commanded the King George on a voyage to the north-west coast of America for sea otter furs in 1785.

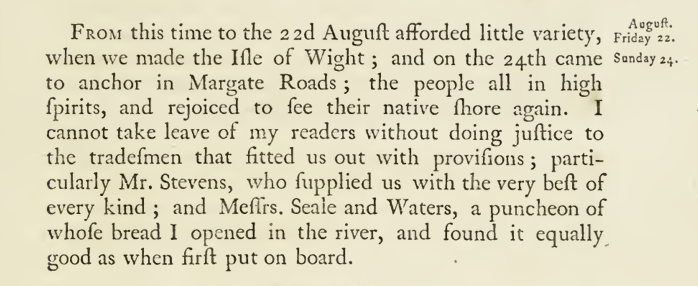

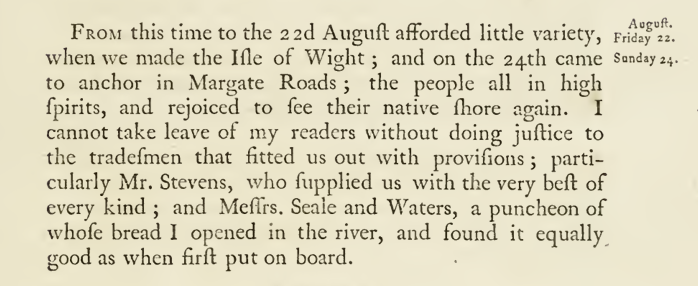

Portlock wrote that when they opened one of the casks on their return to the Thames in 1788, the biscuit (or bread as it was known at the time) was as fresh as when it had been packed.[ii]

This is significant because it demonstrates that, contrary to what modern writers have assumed, sea biscuit could remain edible for several years if it was cooked well and packaged properly. If the broker or contractor sought out a baker with a reputation for producing high quality provisions, ‘creeping biscuit’, stale and riddled with weevils, was not inevitable.

But I had an additional reason for being excited about this chance discovery – because I knew, based on research I had done some years ago into William Richards’ bankruptcy in 1792, that Thomas Walters, one of the principals in the Wapping bakery of Seale and Walters, was one of Richards’ creditors. And I knew that the commercial connections Richards had developed in 1786 and 1787, when he was preparing the First Fleet, had continued into his subsequent ventures.[iii]

In short, the sea provisions for the First Fleet were of a high quality because William Richards went out of his way to find reputable suppliers. High quality product would have been more expensive, and since Richards was on a fixed price contract, this quality came at a cost – to his margin.

________

[i] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, [1798], Sydney: A.H. & A.W. Reed, 1975, Volume 1, pp. 2-3.

[ii] Nathaniel Portlock, A Voyage Around the World. . . in 1785, 1786, 1787, and 1788, London: John Stockdale, 1789, p. 381.

[iii] Order of the Lord Chancellor, ‘In the Matter of William Richards the Younger, a Bankrupt’, 8 April 1794, UK National Archives (hereafter TNA), B1/89, p. 160; Walters v Richards, Court of Chancery, 26 November 1795, TNA C12/469/80.

From Portlock’s Voyage Around the World, 1789

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.