Safety and Salubrity

11/5/20243 min read

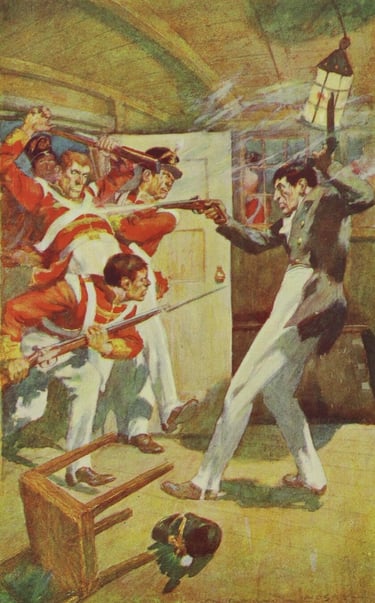

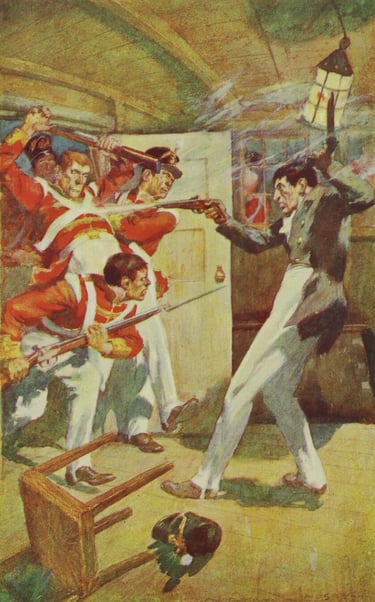

Norman Lindsay, ‘The Mutiny on the Convict Ship [Lady Shore]’ (Illustration for W.H. Traill, ‘The Remarkable Major Semple’, The Lone Hand, 1 October 1909, opp. p. 599)

This does not include another eight vessels where convicts claimed that their fellow inmates were planning an uprising, but no physical evidence was found (see presentation ‘A Convenient Cloak for Cruelty? Mutinies and Conspiracies on Early Australian Convict Transports’).

It was the convicts who suffered from an excess of security. Locked down for long periods in the close quarters of the ship’s prison, the men were vulnerable to communicable diseases such as typhus and dysentery, which spread when hygiene is poor and social distancing impossible.

The average mortality rate in this period (1787 to 1800) was 10%, much higher for men (12%) than for women (4%). As always, averages can be misleading - 40% of these deaths occurred on only three of the ships, which tells us that when things went wrong, they could go terribly wrong. In practice, finding the balance between safety and salubrity was difficult, and it would take time for the lessons to be learned.

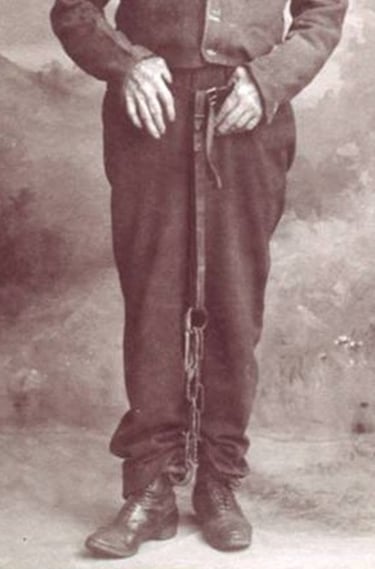

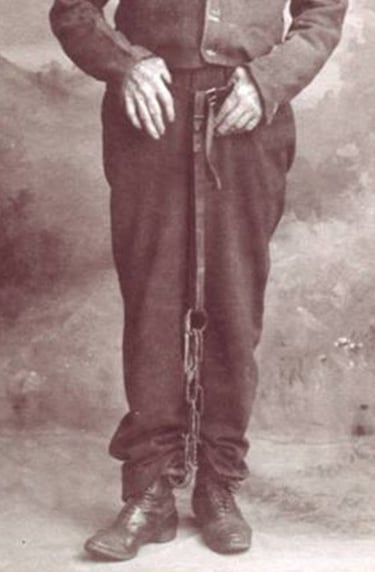

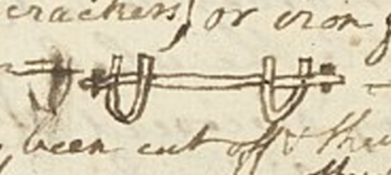

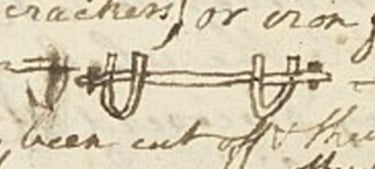

Convict irons were the same as those used in prisons, with a fetter on each ankle, secured by a rivet.

The key to successfully managing a convict ship lay in finding a balance between safety and salubrity – too much freedom and the convicts would mutiny or escape; too little and they would sicken and die of typhus or dysentery.

Escapes were embarrassing and potentially expensive: if the contractors or the ships’ officers were found to have assisted, they would forfeit a substantial bond.

Mutinies were much more serious. Convict informants often claimed that the conspirators planned on executing the ship’s officers, and there were a number of examples from the North American convict trade where mutineers killed the captain when they seized control. The master and the mate of the Lady Shore, a transport bound for NSW in 1797, were killed defending their ship against a mutiny by some of the soldiers.

Historians have generally underestimated the risk of insurrection on convict ships. Of the 35 vessels which carried male convicts to New South Wales in the period 1787 to 1800, one in four encountered a planned or attempted mutiny.

19th century convict shackles

Irons on Bill Thompson, an Australian convict c.1900 (detail), photographed by John Watt Beattie. Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, State Library of Tasmania, 616445.

The ‘bezels’ were joined by a chain around 18 inches in length, and the convicts would pass a tape through the chain and tie it around their waist so they could walk without chafing their ankles.

Sketch of bar fetters by Arthur Bowes Smyth, the surgeon on the First Fleet ship, the 'Lady Penrhyn' (‘Journal of Arthur Bowes Smyth, 22 March 1787 to 8 August 1789’, NLA MS4568, 7 December 1787)

Disorderly prisoners could be double-ironed, chained to the leg of another prisoner, loaded with heavy irons or bar irons (with a metal bar between the fetters rather than a chain), placed in handcuffs or disabled with other devices such as thumbscrews.

The convention developed over time of removing the irons over the course of the voyage as the convicts proved themselves to be trustworthy, and by the time they arrived in the Southern Ocean, where there was no prospect of mutiny, only the most refractory would still be shackled.

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.