Lord of Macquarie Place

From 1794 until the 1820s, a triangle of land in Sydney’s government precinct was home to some of the colony’s most successful emancipists. This newsletter discusses how this happened, exploring the early years of Simeon Lord, one of Sydney’s leading traders, who helped to break the legendary Rum Corps.

Gary L. Sturgess

11/27/202521 min read

Sydney’s Government Precinct

Macquarie Place – a triangle of land in the City of Sydney between Bridge Street and Circular Quay – is one of the few places where we can still see the imprint of First Fleet society. This is where the British established a garden when they first came ashore in January 1788, beginning the work of building a European biota. The colony was administered from here in its first 15 months, while Government House was being constructed a hundred metres up the hill. And this is where Arabanoo, the first (unwilling) Aboriginal ambassador, was buried (off country) when he died of smallpox in May 1789.

It has been a public park since it was acquired by Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1810, and while the eastern end now lies buried beneath streets and buildings, most of the reserve and its obelisk remain, the latter a marker from which all distances in the colony were measured.

The pavement along the western edge of the reserve follows ‘the head of the cove’, the mouth of a stream which divided the settlement in two: this path was first laid down in 1788.

One of the last Aboriginal spearing rituals in Sydney, possibly the very last, took place here in 1809. The first Australian bank was established in Macquarie Place in 1817. And Australia’s first (gas) streetlamp was installed here in 1826.

For two hundred years, Macquarie Place was the government precinct. That was because in January 1788, Governor Arthur Phillip chose this spot to erect his prefabricated house, which was then surrounded by the marquees of his principal officers – his official secretary (who was also the Judge Advocate), the commissary, the provost marshal and the surveyor-general.

And when Government House was completed in early 1789, these men were allocated allotments immediately to the west, along the line of what would later become Bridge Street. In the 1830s, the Colonial Secretary, the Chief Justice and the Surveyor-General still lived along the southern edge of Macquarie Place.

On the demolition of Old Government House in the late 1840s, the public service quarter was expanded: Bridge Street was extended up the hill, with the Old Treasury Building being erected on the north-west corner of Bridge and Macquarie, and the Colonial Secretary’s Building on the southern side.

In recent decades, governments have abandoned this historic district – the buildings remain, but they have been converted into luxury hotels. The Lands Department – built on the site where the Surveyor-General’s marquee was erected in January 1788 – was the latest. Only the Chief Secretary’s building continues to be used as government offices.

This newsletter is concerned with Macquarie Place when it was also the heart of mercantile Sydney, when the most exclusive address in town was dominated by successful emancipist merchants, Simeon Lord, Andrew Thompson and Mary Reibey.

Shadrach Shaw

This part of its history begins in May 1794, when an emancipated convict named Shadrach Shaw was granted a 14-year lease over a triangular block of land in what is now Macquarie Place.

Shaw had arrived on the Royal Admiral in October 1792, with six and a half years of his seven-year sentence still to serve. He was pardoned two months later by the Acting Governor, Major Francis Grose, three weeks after Phillip had sailed for home. In December of the following year, he was granted 30 acres of land at Concord, and in May 1794, only eighteen months after his arrival, he was given this lease in the heart of the government precinct.

Shaw had been a clerk at the Bank of England when he and a colleague set about to defraud their employer of £600, a crime for which Shaw was arrested and tried. He had started out as a lowly teller 17 years before, but for the previous 12 years, he had worked in the Bank’s securities department.

The affair was deeply embarrassing to the board: it led to an overhaul of trading practices, and the creation of a new criminal offence specifically directed at employees who defrauded the Bank. Yet, in response to a petition from Shaw while he was in Newgate prison, the board sent £50 to the master of the Royal Admiral, ‘for extra expenses which he will incur in affording some comforts and conveniences to Shadrach Shaw who is to go to Botany Bay as a convict’. [2] This would not have been enough to pay for a private berth, but £50 would have bought a great deal of ‘convenience’ throughout the voyage.

It was conventional for middle class convicts to carry references from respectable persons at home, and there can be no question that Shaw arrived with such letters. Among those who had given character evidence at his trial was Andrew Abbott, ‘potter to the Prince of Wales’ and a member of the Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, who explained that he had trusted Shaw with thousands of pounds in stocks over the years.

On arrival, he was assigned to Lieutenant Thomas Rowley, the Adjutant of the New South Wales (NSW) Corps, who was responsible for managing the garrison’s affairs. This was an important moment in the emergence of the Rum Corps (as the NSW Corps would come to be known in later years because of their trading activities). In late October, little more than two weeks after Shaw’s arrival, the Britannia, Captain Raven, sailed for the Cape of Good Hope on the first commercial venture of the military officers. It is not known how much Rowley committed on that occasion, but he was one of the principal investors on the second voyage of the Britannia to the Cape in August 1794, risking £250 on his own account (roughly A$100,000 today).

A month later, the Kitty came into port with a shipment of Spanish dollars (3,870 ounces or £1,000 worth). They had been sent out by the home government to cover certain administrative costs and to create a local currency – but there was a real prospect that they would promptly disappear from the colony, used to purchase goods from visiting ships.

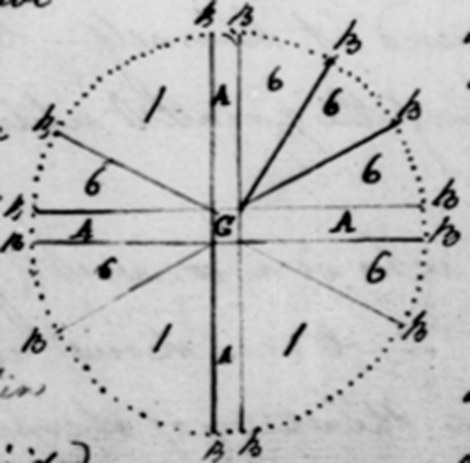

Grose ordered the dollars to be cut into thirds and sixths, creating tokens of a smaller denomination that would be more useful as a currency in the fledgling economy. And to ensure they were not immediately traded away, he ordered them to be clipped, so the intrinsic value of the silver was less than the face value of the new coins. This was much criticised at the time, because it instantly increased the wealth of officers and gentlemen holding silver dollars, but it was probably driven by public policy considerations rather than corrupt intent.

There were several theories about who had come up with this idea, one of them ‘a clerk in the service of the Adjutant’. This was undoubtedly a reference to Shadrach Shaw, although his reward would turn out to be more than ‘a bottle of Grogg and a pair of military shoes’, the story which circulated in the colony. [4]

Around the same time, the NSW Commissary, John Palmer, introduced a system of tradeable commissariat notes – receipts for grain delivered into the storehouse, which could now be traded throughout the colony, thus becoming ‘a species of currency’. It is surely not a coincidence that two significant monetary initiatives were introduced within three months of the arrival of a securities expert. [5]

By October 1793, Shaw was being used as a clerk at Government House, witnessing land grants, among other things. This was a responsibility otherwise reserved for officers and gentlemen such as the colonial secretary, the surgeon-general, and the adjutant. In July 1796, he served as a juror at a coronial inquest, an early way of acknowledging an emancipist’s readmission to respectable society, and the following month, he was confirmed as executor of the will of Henry Brewer, a free settler who had arrived with the First Fleet and had been serving as the provost-marshal.

All of this helps to explain why a convict was emancipated two months after his arrival and later given such a substantial grant so close to Government House. Within a short time, he had erected a house on this triangle of land and then separate ‘warehouse rooms’ alongside. By April 1796, at the latest, he was operating a retail store from these premises, selling beer and consumables such as sugar and soap. And over the next year and a half, Shaw was the plaintiff in sixteen different civil court cases, evidence of his prominence in the commercial life of the settlement at this time.

It is likely that, in the beginning, he was operating as a front for Rowley and possibly some of the other officers. The Britannia, Raven, returned in March 1795 with around 25,000 gallons of Cape rum, and as gentlemen, it was problematic for them to be involved in retail (or rather, to be seen to be so involved). The Commissary, John Palmer, later recalled:

"The officers did not exactly sell it themselves, but they kept women, and those women used to dispose of it, which was the same thing. Immense quantities have been sold in that way." [6]

As early as August 1794, the chaplain, Richard Johnson, explained to a friend at home:

"A convict can go & purchase a bottle, a pint of rum from an officer & gentleman. Some, not quite so open, employ their wash women or others in this way -- & in this way many are making their fortunes. . ." [7]

Many of these shopkeepers and publicans were not mere washerwomen serving as a convenient front, but traders in their own right. The officers actively sought women who were capable of managing their busy households and overseeing their business concerns. The ‘others’ included men like Shadrach Shaw, who had commercial and financial expertise, and could also assist in making them rich.

These relationships worked best when they were symbiotic. Convicts and emancipists with valued skills had leverage, and the most successful officers permitted these men and women to make money for themselves as well. The best documented examples are the Commissary, John Palmer, and John Stogdell; and Captain George Johnston and Isaac Nichols.

But Shadrach Shaw is another – he brought financial expertise which the Rum Corps could use to their advantage, and by the time he sold his business in September 1798, he was evidently trading on his own behalf. He returned to England around 1800 and probably died at Kew in 1825.

Simeon Lord

The young man who purchased his lease, along with the house and warehouse, was Simeon Lord, yet another emancipist trader. Lord had arrived on the Atlantic in 1791, sent out for stealing two hundred yards of calico and muslin from Peel & Co, mill owners at Bury in Lancashire (who were probably his employers). One of the principals of this establishment, a highly successful cotton manufacturer named Robert Peel, was the father of the future British Prime Minister of the same name.

On arrival, Lord worked for a time at the public storehouse, but at some point, he was assigned to Thomas Rowley, and it is possible that the much younger and less experienced man was Shaw’s understudy.

He was not just a naïve country lad. His father, grandfather and great grandfather had been clothiers as well as farmers (as was conventional in the borderlands of Yorkshire and Lancashire at the time), and his childhood home, ‘Dobroyd’, in the hills above Todmorden, boasted a twining mill and a winding mill, powered by water wheel.

Ancestors on both sides had been involved in the wool trade. His father had been a master weaver. His maternal uncle founded a cotton manufactory in Todmorden which would become ‘Fielden Brothers’, one of the great manufacturing dynasties of the Industrial Revolution. [8]

Lord’s parents died within a year of one another in 1786-87, and Simeon and several of his siblings were sent to Bury, a short distance to the south-east of Todmorden and just to the north of Manchester, presumably to stay with relatives. At 16 years of age, his knowledge of warehouse and counting house would not have been great, but it is not difficult to see where his later interest in establishing a clothing mill at Botany Bay came from.

He served his full sentence, finally becoming a free man in April 1797, but Lord had unofficial leave from the Governor several years prior to that. From around 1795, he was operating a bakery and store at the Rocks in Sydney, selling spirits, among other things – no doubt on behalf of Rowley and his associates. By August 1796 (the earliest date for which we have records), he was also bringing legal actions in the civil court, half a dozen of them while he was still serving his time.

In September 1798, the same month that Lord purchased Shaw’s business for £160, Governor John Hunter granted him an auctioneer’s licence and a liquor permit. Surety for the latter was provided by William Stephenson, another emancipated convict who had come out with Lord on the Atlantic and risen to become the storekeeper at the Commissariat, a position of great trust. The Colonial Secretary, David Collins, said of Stephenson:

". . . his conduct had been uniformly that of a good man, and he had shewn that he was trustworthy by never having forfeited the good opinion of the commissary under whom he was placed in the provision-store". [9]

When Stephenson passed away in late 1798, the executors of his estate were another two trusted emancipists, Simeon Lord and Shadrach Shaw.

Lord now began to assert his independence. Evidence of commercial transactions in this period is limited, but we know that he acted as agent for John Cameron, master of the Barwell, which was in port between May and September of 1798, and that over the next couple of years, he did business with the masters of several other ships.

Taking on the Rum Corps

In the military interregnum, from December 1792 to September 1795, when the officer commanding the NSW Corps ruled the settlement as Acting Governor, the military acquired a monopoly over external trade. Grose closed the public store which Phillip had established on the western side of the cove, where the masters of visiting ships were obliged to sell their cargoes to the public at reasonable prices. He used the Commissariat to purchase spirits from some of these vessels and sold them to the officers at a concessionary rate. On one occasion, two exiles (gentlemen convicts who had been required to take themselves out of the kingdom rather than be transported) were physically detained by the military guard and removed from a ship when they went on board to trade.

The monopoly was substantially weakened when Governor Hunter arrived in September 1795. Residents were now permitted to go on board the ships and buy from the masters direct, although the officers and gentlemen still enjoyed a substantial advantage, since very few others had access to international bills of exchange. The officers continued to dominate the trade in spirits (through smuggling), but their control of the wider import trade was severely limited, as an ex-convict, Matthew Everingham, noted at the end of August 1796:

"This monopolizing trade of purchasing the whole Cargo of the Vessell in Shares is very much hurt since the arrival of Governor Hunter in this Country who has gave leave to all free persons to go on board & purchase according to their circumstances. . ."

Everingham observed that there were a few who had been wise in their investments and were now able to compete head-to-head with the gentlemen. [10]

By 1798, the officers’ solidarity had broken down entirely, as visiting masters and merchants appointed local agents to dispose of their cargoes. When the Barwell arrived in May of that year, she was carrying an investment sent by Michael Hogan, who had come to NSW in 1795 and 1798 as master of the Marquis Cornwallis. Hogan had appointed John Macarthur, one of the foremost Rum Corps officers, as his Sydney agent.

The following month, Hunter sought to assist the small settlers by encouraging them to establish district cooperatives so they could purchase direct from the ships in bulk. He met with limited success, but the officers and gentlemen were now deeply concerned, some of them entering into an agreement not to bid against one another while ships were in port. One measure of their desperation is the invitation they extended to one of gentlemen-in-exile whom they had previously shunned. He declined the offer.

Simeon Lord was also challenging the officers with a new business model, acting as the agent for the masters of visiting ships, and selling their investments on commission, usually by auction. Articles that did not sell while the ships were in port could be warehoused and sold at a later time, when the market was more favourable. Lord’s package of services also included the hospitality of his own home while masters and mates were in town.

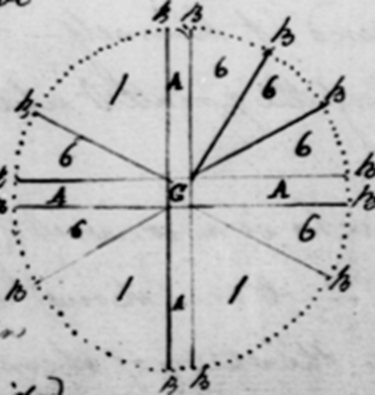

Sketch by Robert Murray, 4th Mate of the Britannia, Raven, showing how the Spanish dollars were clipped and cut [3]

Simeon Lord, c. 1830 [11]

Max Dupain, Macquarie Place in the 1940s [1]

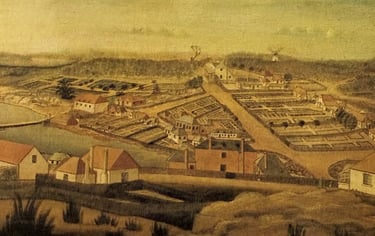

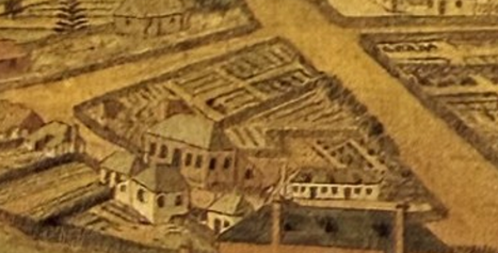

A view of the east side of Sydney around 1800, showing Bridge Street and the triangle of land occupied by Shaw and Lord [14]

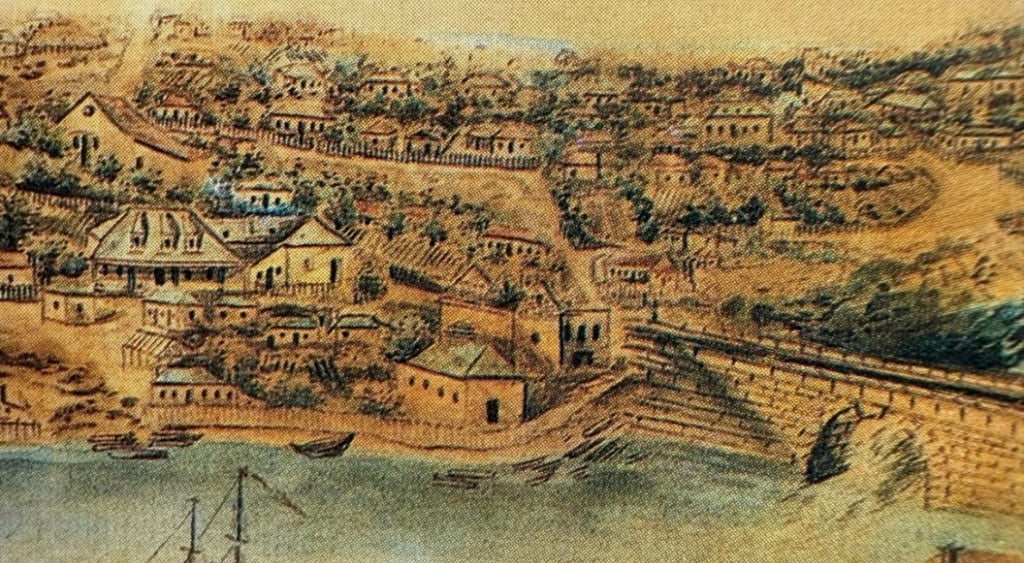

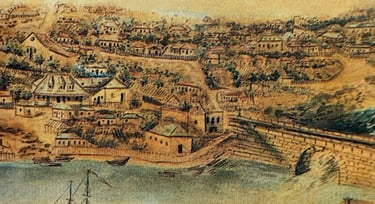

John Lancashire’s painting of the settlement, dated to around 1803 but probably completed the following year, shows the new stone bridge, with Lord’s partly completed house at the left end, as well as his old house and the warehouse (now with three dormer windows) somewhat to the left of that.

The property immediately to the north-east of Lord’s house was occupied by Thomas Randall, a tinman, who built a stone house and a workshop there in 1803, opening a new shop ‘on an extensive scale’ in October. Lord purchased Randall’s lease in 1807 and operated his warehouse and retail business from there.

The next property in the row, occupied by a milliner in 1803, was acquired by the emancipist farmer and businessman, Andrew Thompson five years later. He also purchased the next lease, which had been owned for some years by the emancipists, William Chapman and Ann Mash, who operated a number of successful businesses in the colony. Thompson immediately set about building a substantial two-storey house on this site, although he never lived in it, passing away in October 1810. The premises were occupied by a variety of different tenants over the years, including the new Judge Advocate, Ellis Bent, from March 1810, while a new house and office were being built for him across the road.

Thomas Reiby acquired the neighbouring lease in 1803 and built a stone house and warehouse. He passed away there in April 1811, and his widow, the formidable Mary Reiby, took over the management of his business. It was here that the Bank of New South Wales opened for business in 1817, the Colonial Treasury operated for a time in the 1830s, and the Royal Exchange was temporarily based around 1840. It was still known as the Reiby House as late as 1847.

At the end of the row, closest to the cove, was the house and workshop of Francis Cox, an emancipist blacksmith, who sold his services to government and visiting ships’ captains. His daughter married the barrister, newspaper editor and advocate of the emancipist cause, William Charles Wentworth, son of a gentleman exile, and he based himself at these premises from the 1820s.

The White House

Lord’s townhouse was a Sydney landmark, testament to his faith in the colony. The emancipist public official and author, David Mann, described it in 1809 as ‘by far the most magnificent in the colony’. Two decades later, at a time when there were a number of magnificent residences in the town, it was still referred to as ‘Mr Lord’s extensive house’.

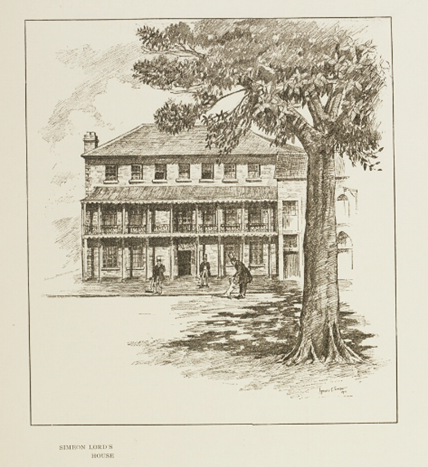

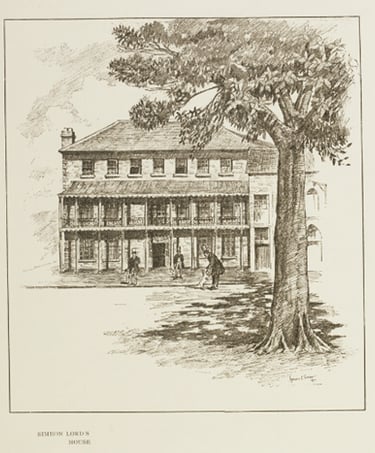

There are no clear images of the house until shortly before it was demolished in 1908, but the following sketch, made in 1911 based on the research of the Sydney historian, Charles H. Bertie, is a good representation of how it looked in its heyday.

Sidney Ure Smith, ‘Simeon Lord’s House, Macquarie Place’, 1911 [19]

Henry Waterhouse, commander of a naval vessel based in the colony, explained to Sir Joseph Banks in 1806:

"When I arriv’d in the Reliance at Port Jackson in 1795 Simeon Lord was a Convict in the service of Capt Rowley of the New South Wales Corps, or he had just left him, either his time of servitude being out, or he was emancipated. From his good conduct Capt Rowley told him if he set up in any business he would assist him, in consequence he commenc’d Baker & retailer of Spiritous Liquors, & I am told got himself taught both to read & write. For a length of time it was the usual custom when a Ship arrivd for a few individuals to purchase the whole Cargo, which they parcelled out into lots, & sold at a very advanc’d price to those who retaild it, so that it often happen’d that the original purchasers of the Cargo made out the allotments on paper, & receiv’d from the retailer from 20 to 100 per Cent before the Cargo had been broke up.

"The Masters of the Merchant Vessels finding this out wish’d to have a share of this profit likewise, & began to sell by Auction, when Simeon Lord commenced Auctioneer. I understood he had five per Cent on the Cargo for selling it & collecting the Bills (being answerable they were good ones) it was suppos’d five per Cent was not half his profit. He soon afterwards built a substantial store house capable of containing a large Cargo, to which he added a good & neat dwelling House, at which a stranger on his arrival might Lodge & Board, or eat by himself. This was so convenient to the Master & Mates of Merchant Vessels, that Lord got the disposal of most of their investments." [12]

In 1800, Lord joined a syndicate of emancipists and free settlers to purchase direct from the Minerva, and the following year, when an American ship came into port, it was reported that half of her cargo of butter had been bought by the military and the other half by Lord.

We have little evidence of these transactions until the launch of the Sydney Gazette in 1803, but in that year alone, Lord acted on behalf of eight ships at least. The Experiment, Withers, which arrived in June 1804, provides an example of how he operated. A week after she had come to anchor in the cove with 130 female convicts (and two men), Lord advertised her extensive investment for sale, by retail or wholesale, at his warehouse.

"Cash, Copper Coin, or good approved Bills on delivery of the Articles; but to such Persons as Mr. Lord may approve, two months prompt will be allowed, at the expiration of which Period Bills ready for immediate consolidation will be expected, and good allowance made to wholesale purchasers for prompt payment." [13]

In mid-August, Captain Withers offered the remainder of his cargo at a discount, ‘at Six Months Credit. . . upon approved Security’: Withers would have been completely reliant on Lord as to which of the residents was a safe credit risk. At the end of the month, Lord called on all persons who had purchased some of the Experiment’s investment on credit to pay the outstanding sums within 14 days: again, Withers was dependent on Lord and his standing in Sydney society, to collect these sums.

As the ship prepared to sail late the following month, Lord maintained a ‘letter box’ at his warehouse, so that residents could send letters home by this ship, and he helped to organise a return cargo of hardwood and coal, brought down from Newcastle by Thomas Reiby in the Raven.

Macquarie Place

Lord was still operating from Shadrach Shaw’s old warehouse. The detailed images below, taken from a painting attributed to Thomas Watling and dated to around 1800, shows Lord’s house in the triangle of land that would become Macquarie Place, with a much larger warehouse to the left, and gardens behind. The road that would become Bridge Street runs along the right-hand side, terminating at Government House, with the officers’ houses and gardens on the right.

Detail of John Lancashire’s ‘View of Sydney, Port Jackson’, c.1803 [18]

The ground floor consisted of four large reception rooms, with a hall, closet and lobby, and in a basement at the rear, two cellars, a large kitchen, a pantry and a well dug eight feet deep into solid rock. There were a number of outbuildings, including a large ‘out kitchen’, and another well.

On the second floor there were three more large rooms, a master bedroom with two dressing closets, another large store or dressing room, a large lobby, and a veranda across the front of the house with venetian blinds. The stone walls were stuccoed and finished with cedar panelling. There were 14 bed chambers on the upper level, with a hall 10 feet wide, once again with cedar panelling.

By the time the townhouse was completed in 1809, Lord had other interests. He had acquired his first ship in 1799 and increasingly became involved in international trading ventures of his own. In 1807, he brought out a young man, the son of a skinner from Southwark, and opened a hat manufactory in the warehouse next door. From 1812, he was increasingly focused on manufacturing, establishing his water-powered clothing factory at Botany two years later.

While he and his sons continued to use the Macquarie Place mansion as a townhouse for many years, Lord had lost interest in being a middleman. He offered the house to government in 1814 and again in 1817, the offers being refused because the government had no need of a building ‘so extensive and expensive’.

From 1828 until 1834, ‘that spacious building in Macquarie-place’ was occupied by Cummings New Hotel and then used for several years as a public bazaar. From 1851 to 1870, it was the Star Hotel, from 1873 to 1883, a branch of the Lands Department, and in 1904, now a pale shadow of its former self, it was occupied by a small branch of the Bank of NSW and the Exchange photographic studios. The building that had once been most magnificent house in Sydney was torn down in 1908, a century after its construction.

Lord of Macquarie Place

Although he had not lived there for several decades, Lord was still referred to as ‘Mr Simeon Lord, of Macquarie Place’ until his death in 1840, and when his widow passed away in 1864, and then his sons in the three decades that followed, he was still remembered as Lord of Macquarie Place.

A closer view of the east side of Sydney showing Lord’s house and warehouse in the triangle of land.

In 1803, Lord started to build a much larger house on the south-west corner of the plaza, just across the street from his original premises, and four years later, purchased a workshop next door for use as his warehouse.

The Acting Governor, William Paterson, gave him a 21-year lease over the original Shaw grant in July 1809. Given that Governor Macquarie was about to arrive, and that by convention, all grants and leases had to be submitted to the new Governor for his approval, the propriety of this transaction is open to question.

Macquarie renewed all of Lord’s other leases, but decided that the triangle of land should be acquired by government and set aside as a public reserve (to be named after himself). Lord had been thinking of erecting another substantial house on this site, but Shaw’s house and warehouse were unused at that time and the decision did not affect his business.

Macquarie would come to develop a high regard for Lord, later appointing him as a magistrate, but a comment made some decades later by the Presbyterian clergyman, John Dunmore Lang, suggests that in 1810, the new Governor had been uncomfortable with an emancipist holding this prime piece of real estate so close to Government House.

". . . there was Mr. Simeon Lord, whose right to an allotment of ground adjoining the Government domain the Governor had recently called in question. . ." [15]

Lord was not compensated until 1828, when the government paid him £6,500 for ‘the triangular spot of ground enclosed within railings in front of Macquarie Place’ and another small plot close to the Government Wharf (behind what is now Circular Quay).

The Emancipist Traders

In 1803, the government pulled down the wooden bridge which spanned the stream (later to be known as the Tank Stream) and replaced it with a more substantial edifice made of stone. Around the same time, and presumably in response to the improvements which the new bridge would bring, several successful emancipist traders bought up small holdings along the eastern edge of the tidal delta and began to build more substantial premises there.

An article in the Sydney Gazette in October of that year noted that ‘All the new buildings in the Row are designed to be erected uniformly in front, and in honour of the New Bridge it is not unlikely that it may derive its future name from that Edifice.’ [16] This street, which ran north-east from the bridge to Government Wharf (and still exists as a pavement along the western edge of the reserve), was briefly called Bridge Street, but this appellation did not last and that name was later given to the street which crossed the bridge and made its way up to Government House.

As noted above, Lord acquired the lot in the south-west corner, immediately adjacent to the bridge, and across the street from the property he had purchased from Shadrach Shaw. There he erected a three-storey sandstone townhouse, the largest building in Sydney at the time. He later claimed that he had been encouraged to build the house by Governor King, ‘in Expectation of it answering as a Tavern from and by certain Indulgences he would grant. . .’ It took six years to complete and cost Lord more than £15,000, three times the original estimate. [17]

Macquarie Place, c. 1907, showing Simeon Lord’s house shortly before demolition [20]

________________________

For reasons of space, this newsletter is not fully referenced. Readers who want to know more about particular details can contact the author.

[1] Max Dupain, ‘File 04: Macquarie Place, 1940s’, State Library of NSW (hereafter SLNSW), ON 609/Box 28/No. 505.

[2] David Kynaston, Till Time’s Last Stand: A History of the Bank of England, 1694-2013; (W. Marston Acres, The Bank of England from Within: 1694-1900, London: OUP, 1931, pp. 251-252.

[3] Robert Murray, ‘Journal of a Voyage from England to Port Jackson, New So Wales. . .in the Ship Britannia, Mr W. Raven Commr, by Rt Murray, 16 February 1792 to 3 March 1795’, Peabody Essex Museum, Journal 26, Microfilm 56 Reel 215, p. 143.

[4] Ibid., p. 143a.

[5] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [1798], Sydney: A.H. & A.W. Reed, 1975, Vol. 1, pp. 206-207.

[6] Evidence of John Palmer, ‘Report from the Select Committee on Transportation’, Ordered to be Printed 10 July 1812, House of Commons Papers: Reports of Committees, (341) 1812, p. 64.

[7] Johnson to Stonard, 11 August 1794, George Mackaness (ed), ‘Some Letters of Rev. Richard Johnson’, Part II, Australian Historical Monographs, Volume XXI (New Series), No.20.

[8] Brian R. Law, Fieldens of Todmorden: A Nineteenth Century Business Dynasty, Littleborough, Lancs.: George Kelsall, 1995.

[9] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony. . . , Vol. 1, p. 329.

[10] Everingham to Shepherd, 30 August 1796, ‘Letterbook of Matthew James Everingham’, Ritchie Family and Business Correspondence, University of Melbourne, pp. 8-10.

[11] ‘Simeon Lord’, c. 1830, Miniature, watercolour on ivory, SLNSW MIN 92.

[12] Waterhouse to Banks, 10 June 1806, SLNSW, SAFE/Banks Papers/Series 23.42

[13] Sydney Gazette, 1 July 1804, p. 4.

[14] Thomas Watling (att.), ‘Sydney Capital NSW, founded by Governor Phillip. . .’, c.1800. (detail), SLNSW DG 56.

[15] John Dunmore Grant, An Historical and Statistical Account of New South Wales, London: A.J. Valpy, 1837, Vol.1, p.128

[16] Sydney Gazette, 23 October 1803, p.3.

[17] Lord to Macquarie, 18 July 1814, Colonial Secretary’s Papers, 1788-1825. Museums of History NSW, State Archives, 4/1730, pp.207-212.

[18] John William Lancashire, ‘View of Sydney Port Jackson, New South Wales, taken from the Rocks on the western side of the Cove’, c. 1803, SLNSW DG SV1/60.

[19] Charles H. Bertie, Old Sydney, Illustrated by Sidney G. Smith, Sydney, 1911, p. 54.

[20] ‘Macquarie Place, Sydney, c. 1907’, Glass negative, City of Sydney Archives, A-01000289.

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.