Layout of a Convict Ship

10/12/20246 min read

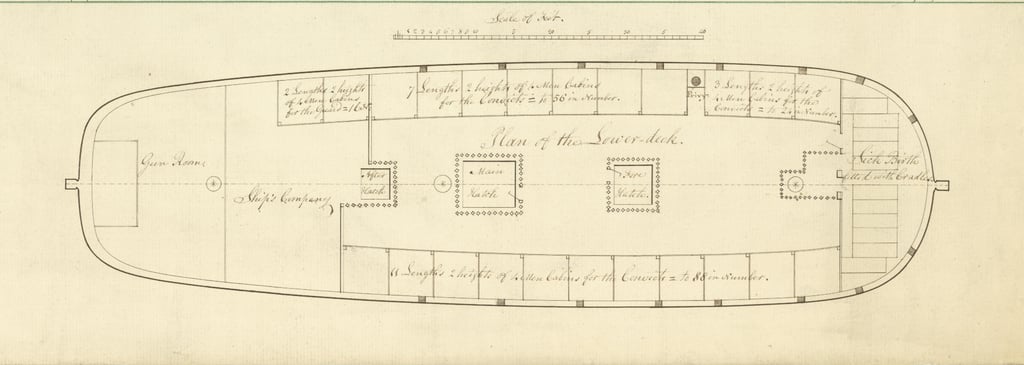

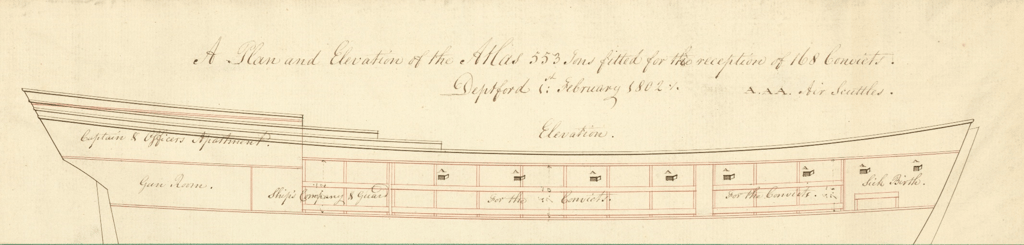

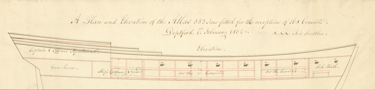

The earliest known plan of a convict transport is for the Atlas (1802), although she was broadly representative of the transports used over the previous decade – with the exception that in the early years, tubs down the end of the prison were used as toilets rather than water closets located along the sides.

The Upper Deck

None of the surviving journals or memoirs describes the upper deck of a convict transport in the late 18th or early 19th centuries. The weather deck would have been cluttered with boats and booms, goat pens and chicken coops. The longboat, around 36 feet in length, was stored on top of spare topmasts in the ship’s waist, immediately in front of the main mast. Jolly boats, small, light craft 16 to 18 feet in length, were suspended from hoists (later known as davits) on either side at the ship’s stern, so they could quickly be lowered if there was an emergency (such as someone falling overboard). On sailing, the weather deck might also be burdened with stores, and barrels of water and provisions for the convicts, until space could be cleared below.

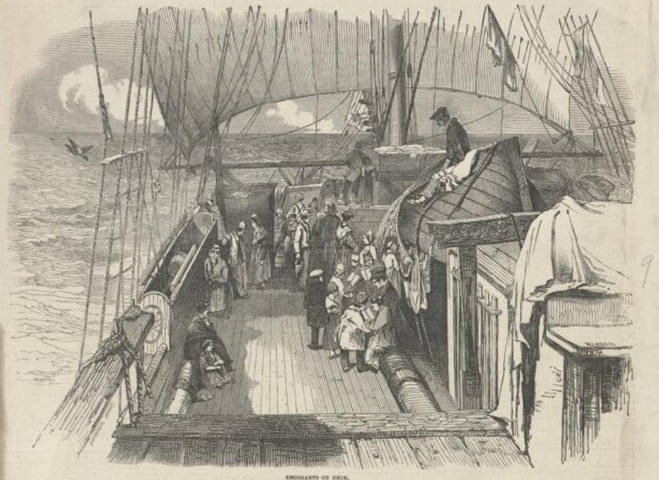

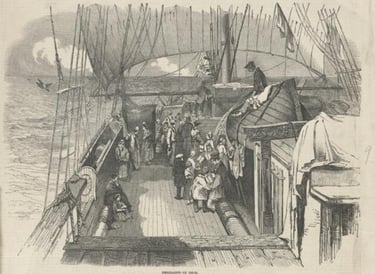

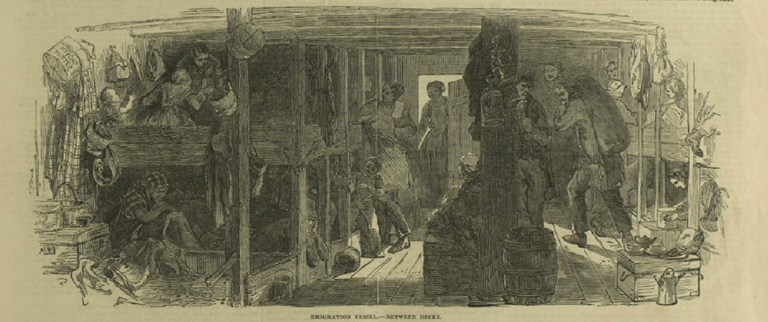

In trying to imagine the upper deck of a convict ship, sketches of emigrant ships published in the 1850s are the most useful. On most of the convict transports in this early period, only small groups of male prisoners were allowed on deck throughout the day for several hours at a time. This was for security reasons, since mutinies were most often launched when the convicts were on deck. Unless they misbehaved, women had the freedom of the upper deck, since they were not seen as a security risk.

Plan of the Atlas, convict transport (1802) (‘A Plan and Elevation of the Atlas’, UK National Maritime Museum, ZAZ0329)

John Skinner Prout, ‘Emigrants on Deck’ (‘Scenes on Board an Australian Emigrant Ship’, Illustrated London News, 20 January 1849, p.40

Section of the Atlas (1802)

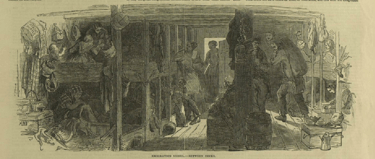

‘Emigrant Vessel – Between Decks’ (Illustrated London News, 10 May 1851, p.387)

On ships without a raised quarterdeck (the area behind the main mast), a barricade was often installed to provide the officers with some protection in case of a convict uprising. Two of the First Fleet transports had raised quarter decks, but on another two, wooden barriers were erected, three feet high and tipped with ‘pointed prongs of iron’. The barricade on the Hillsborough (1798) was described as a grating either side of the mast to the gangways. (On slave ships, these could be eight feet high and protrude two feet over the sides of the ship).

Needless to say, such an imposing barrier impeded the efficient working of the ship: the master of the Royal Admiral (1800) did not erect a barricade until well into the voyage, and only then because of passengers’ fears about a mutiny; the one on the Atlas (1802) was taken down two days before she sailed into Sydney Harbour.

The Convict Quarters

The men’s prison was usually on the lowest deck, which meant that on ships with three decks, it was two levels down, on what was known as the orlop deck. The arrangements differed from ship to ship, but in general, the men were housed forward (downwind) and as far as possible away from the officers and gentlemen who were accommodated at the stern. When the prison was on the orlop, it took longer for the men to make their way up two flights of steps or ladders to the weather deck, particularly when they were laden with irons, which meant less time for fresh air and exercise. This was not an ideal location for large numbers of prisoners, but the orlop was also used when troops were being carried out to the East Indies, since there was often no alternative.

It is best to think of the prison as a dormitory; indeed, the journal of the Scarborough (1787) refers to the convict quarters as ‘barracks’. There were two tiers of berths or cabins, roughly six feet square, lining each side of the deck. Each level held four convicts, so that each man had around 18 inches in which to sleep. To us, this seems grossly overcrowded, but these same arrangements had long been used for the transportation of troops. The great difference, of course, was that soldiers were not shackled, and they were at sea for eight to ten weeks rather than six to eight months.

On some of the convict transports, there was plenty of headroom. The prisons on the Minerva (1799) were ‘eight feet high between decks, with a scuttle one foot square to each berth on each side of the ship, beside three large hatches to permit the free circulation of air’. But again, we must be aware of the differences: the orlop deck on the Pitt (1791), a former East Indiaman, was only five feet beneath the beams, and being so close to the waterline, there would have been no scuttles.

At either end of the prison was a bulkhead made of hardwood two inches thick and studded with iron nails, with large padlocked doors. These partitions were sometimes enclosed for security reasons, but on most of these early transports, the bulkheads were left open, with the wooden bars around four inches apart, allowing the air to circulate. While they were in the tropics, the prisoners would crowd against these bulkheads, trying to get as much fresh air and sunlight as they could.

Outside the bulkheads, at the foot of the hatchway, there was a small antechamber from which activity inside the prison could be monitored by the ship’s officers and the sentries. Fires were generally not allowed in the prison, and at night, lanterns would be kept burning in this space so the prisoners could make their way to the tubs and the sentries could see what was happening inside. On some ships, water kegs would be placed there throughout the day from which the messes could collect their rations, and bathing tubs for the female prisoners were sometimes located in this outer chamber, for reasons of privacy.

Within the prison, the space between the two tiers of cabins was free of other furniture, although boxes containing personal belongings were kept there and used as seating. By the 1820s, the women’s quarters were being fitted with tables and shelves ‘upon which to iron their clothes and stow away their tea-ware’.

Initially, the privies consisted of nothing more than tubs stationed down one end of the prison, which were taken up on deck every morning and emptied. In 1797, ‘close stools’ or ‘night chairs’ were introduced, enclosed wooden cabinets with a toilet seat and a lead or pewter pan inside. Water closets were installed around 1801, located along the sides of the ship rather than being clustered together down one end. It is not fully understood how these worked, but they had water cisterns not unlike the mechanisms in a modern toilet, and lead pipes which emptied the waste direct into the sea (see this Catspaw on privies on convict ships).

On most of the ships, there was a sick bay at the head of the prison, although if there was a great deal of disease on board, the captain might also take over the women’s quarters, part of the gun deck, or one of the galleries at the stern.

The arrangements for the women differed depending on their numbers and the configuration of the vessel. In most cases, the women’s quarters – the ‘nunnery’, as they were sometimes known – were located at the rear of the prison deck, separated from the men. In several cases, the women were housed in part of the great cabin or in specially constructed quarters just in front. They were not in their quarters for much of the day, since they were allowed the freedom of the upper deck throughout the voyage.

If we want a broad impression of what life was like in the convict quarters of these early Botany Baymen, it is best to study the sketches of emigrant ships bound for New South Wales, published in the 'Illustrated London News' from the 1850s. There are important differences – emigrants were not kept in chains and they were generally allowed on deck for as long as they liked – but these drawings are closer to the reality than the lurid images of small slimy cells painted by amateur historians who have sought to imagine the convict experience.

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.