Governance

11/1/20242 min read

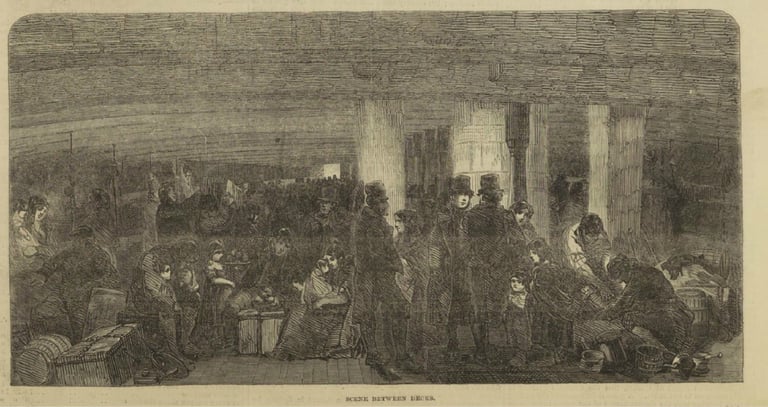

Scene between Decks on an Immigrant Ship, Illustrated London News, 6 July 1850, p.17

On first coming aboard, the convicts would be assigned to messes – usually the naval mess of six – the primary social unit for issuing, cooking and eating meals. The mess was also used for allocating work duties such as washing clothes and cleaning the prison. Some of the ships’ officers and surgeon superintendents allowed the men and women to select their own messmates, but this was apparently not done in the early period. In some cases, the convicts were also organized into larger ‘divisions’ to assist in regulating them while they were on the upper deck for exercise.

Men with skills that were useful in working the ship – sailors, carpenters, butchers, hairdressers, clerks – would be assigned to working messes so they could more easily be released from the prison. And as noted above, middle class convicts could make arrangements (probably for a fee) to mess together. There is also evidence that young women were assigned to messes with older and more stable figures, and mothers with young children were placed together. (See Newsletter on the First Fleet Messes)

Trusted prisoners (and men and women who were prepared to risk the disapproval of their fellow inmates) were appointed to supervisory roles – boatswain of the prison, boatswain’s mates, captains of the decks, captains of divisions, mess captains or monitors. It was from amongst these men that the overseers were chosen when the First Fleet arrived, and the various work parties were established.

Other men and women were given perquisites in return for taking on the responsibility of support roles – convict cooks and cook’s mates; assistants to the stewards in serving out the provisions; guards over the provisions; watchmen of the prison; ‘surgeryman’ in charge of the hospital and other attendants to the sick; men assigned to keep the privy cisterns filled with water or to maintain the windsails; butchers; barbers; teachers and so on.

The men selected to oversee the provisions were often chosen by the convicts themselves, as a form of reassurance that they were being issued with their full entitlement. While the evidence is fragmentary, we know that on some ships, the convicts elected their own cooks and boatswain’s mates.

There were also a few cases where the convicts organized themselves into watches to prevent thieving, and ‘committees’ to try and punish offenders. The most famous example is the ‘board of honour’ organized on the Hillsborough (1798) to track down the watch of the Sir Jeremiah Fitzpatrick, the ‘inspector of health’ to the convict transports, stolen when he came on board prior to sailing to ensure that the prisoners were being properly treated. Under threat of being discovered by his fellow prisoners and given exemplary punishment, the offender quietly gave up the watch.

There are other examples – the convicts on the Bencoolen (1819), who established a jury of 12 to adjudicate their differences and to enforce the prison regulations; and the men on the Albion (1823) who formed a ‘society for the suppression of vice’.

Not all of the ships’ officers and surgeon superintendents were comfortable with the prisoners self-organising, and they suppressed such initiatives which smacked of republicanism.

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.