Going Ashore in January 1788

There has long been a debate over where the British went ashore on the 26th of January 1788, to establish their first permanent settlement on Australian soil – did they land on a sandy beach on the east side of the stream, or was it on a rock platform on the west? This newsletter discusses the evidence that has come to light over the past decade or more, which establishes that the landing probably occurred on the west side.

Gary L. Sturgess and Michael Flynn

1/26/202540 min read

Warrane (Sydney Cove), 26 January 1788

The Supply anchored in the cove late on the afternoon of the 25th, having made her way round from Botany Bay with 60 or 70 tradesmen and a marine guard to begin the work of clearing the bush for encampment.

At first light on the 26th, Governor-designate Arthur Phillip and a small party of marines clambered down into the boats and made their way ashore. There had been no violent encounters with the indigenous inhabitants at Botany Bay nor in their exploration of Port Jackson several days earlier, and Phillip thought that they might once again avoid the use of force, but it is likely that a party of marines was sent ashore first to secure the landing. The men chosen for this task were grenadiers, marines who specialised in amphibious assaults and skirmishing. Marine Lieutenant George Johnston would later claim that he was the first man on shore, and given that he had previously commanded grenadiers, this might well be right.[1]

On landing, Phillip and his officers walked the ground, sketching out the basic outlines of the settlement, and laying down ‘lines of limitation’ designed to prevent the convicts from wandering off into the bush. There wasn’t time to erect wooden barricades, which is what the ‘lines’ usually consisted of in military camps, and they probably did nothing more than cut blazes into trees, possibly daubed with whitewash.[2]

The boats then ferried the tradesmen ashore: sawyers and carpenters, blacksmiths and shinglers, farmers and gardeners selected from amongst the convicts, seamen and marines. Much of that day was spent at the head of the cove, in the south-west corner of the proposed settlement, felling trees, slashing undergrowth, clearing away rocks and putting up marquees and tents for the marines, but scouting parties were no doubt sent out into the bush, and sawyers dispatched to search for trees that might be suitable for construction.[3]

Work stopped around two o’clock, and the men walked back down the cove to a spot close to where they had landed in the morning. A flagstaff had been erected there on which the British colours were raised, and the men stood around as Phillip and the other officers drank toasts to the royal family and the success of the colony, interspersed with volleys of musket fire from the marines.

Contrary to the claims later made by several eminent historians, there was no flag-raising ceremony that morning when they first went ashore.[4] (See Catspaw on the question of two ceremonies. ) The ceremony was evidently an afterthought, with Phillip sending someone on board the Supply for a flag.[5] Nor is there evidence that work was done on the east side of the settlement that day, preparing the ground for the Governor’s residence.[6] Ever the pragmatist, Phillip was at work on the west side, getting the convicts and marines on shore and under cover as quickly as possible, as he had been directed by the Home Secretary prior to leaving England.[7]

At the end of the ceremony, the convicts and seamen returned on board the Supply, and the marines marched back up to their camp at the head of the cove, ‘to guard the works as they advanced towards completion’.[8] The rest of the fleet came to anchor at the mouth of the cove shortly before sunset.

The Debate

There has long been a debate as to where Phillip went ashore that morning: a sandy beach on the eastern side of a stream which ran into south-west corner of the cove, or a rocky platform on the west.

It matters because this is where British settlers first established a permanent settlement: this is where the invasion began. (There was no violence that day, but invasion seems the appropriate word for a process where heavily armed strangers made a permanent camp in someone else’s country without their consent.)

And where Phillip chose to go ashore that day says a great deal about what kind of man he was – it matters whether he was most concerned with his own accommodation, or whether he was focused on getting the convicts and the stores on shore.

Understanding how the settlement was laid out (and why), and how the settlers interacted with each other and their physical environment, are essential to an understanding of how the early colony worked.

Until 1964, the prevailing view was that the landing occurred on the west side. Differences first emerged in 1900 with the publication of a paper by Alfred Lee, an antique book collector and one of the leading lights in the recently established Australian Historical Society, who argued for a landing on the east side, based on a drawing dated to August 1788.

The two camps continued to disagree, with periodic battles in the press, until 1964, when the east-side advocates had a resounding win with the findings of a report commissioned by the Sydney City Council, and the erection of a flagstaff and monument in Loftus Street behind Circular Quay, which stands to this day.

There continued to be dissenters, notably at the Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority, the government agency responsible for managing The Rocks (site of the original township), and over the past decade, a number of discoveries – in documents, maps and drawings – have confirmed that the rocky western side was the most likely location. This newsletter discusses the evidence.

Layout of the Cove

Sydney Cove has a U-shape today, created with the construction of a ‘semi-circular quay’ at the southern end in the 1840s, but in 1788, it was a lopsided V, with a stream running into the south-west corner. (Later known as the Tank Stream, this was located a little to the west of lower Pitt Street today.)

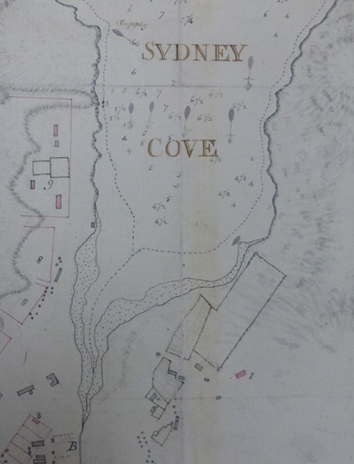

The head of the cove was tidal: at high tide, sea water made its way as far up as Bridge Street today. Over the centuries, dirt and sand had washed down this watercourse, creating sand flats along the lower parts of the small delta, and beaches on either side of the mouth (evident in the detail from the Dawes chart of July 1788 below).

Away from the mouth of the stream, the cove was lined on both sides by rocks, with the floor quickly dropping away into depths of four or five fathoms (7 to 9 metres). In their study of Sydney’s bushland prior to European settlement, Benson and Howell described the shape of the cove and the native flora:

‘Below Bridge Street the Tank Stream spilled out on to a small alluvial fan which probably had Swamp Mahogany, Eucalyptus robusta, on the higher parts and Swamp Oak, Casuarina glauca, nearer the salt water. Today Vaucluse Bay near Vaucluse House provides a similar appearance to the 1788 Sydney Cove, though on a smaller scale. It has a small sandy beach with Swamp Oak and Forest Red Gum on the flats and a small creek. On each side, sandstone outcrops to form the shoreline, supporting a few old Port Jackson Figs, Ficus rubiginosa.’[10]

The photograph of Vaucluse Bay below shows this pattern: shallow water and sandy beaches at the southern end, rock platforms and deeper water further along.

Sedimentation at the southern end of the cove was much worse by the 1840s, when it was necessary to build a quay so that large vessels could moor, but for someone wanting to go ashore there in 1788, it would have been necessary to climb out of the boat and wade up a sandy beach. Work was begun on a wharf as early as March of that year.[12]

In 1803, the captain of a visiting ship was critical of this wharf (known as the Governor’s Wharf), since no goods of any weight could be landed there, and it was necessary to throw casks of wine and porter overboard from the launch and swim them ashore. [13] That same year, the wharf was extended by 30 feet, ‘by means of which Boats belonging to His Majesty’s Vessels may land at low water without the inconveniences to which they were before exposed’. [14]

What was remarkable about the cove in 1788 was not the sandy beaches but the rock platforms, which in some places were almost like man-made wharves. When Phillip first visited the cove on the 22nd of January, the boats were moored alongside the rocks on the western side.[15] And on his return to Botany Bay the next day, he explained to the other officers that the harbour had ‘many rock eminences, quite perpendicular & perfectly flat at top wh. will answer every purpose of loadg and unloadg the Largest Ships.’ [16]

Once they had warped into the cove on the morning of the 27th, some of the transports were ordered to anchor close to these rocks, as the surgeon of the Lady Penrhyn described in his journal:

‘The Ships some of them lay so near the Stone cliffs that you may wh ease jump from the Ship on Shore. . . The Water here even to the very side of the shore is 5 & 6 Fathoms & exactly like a Canal in a Garden, you may wh ease fasten the Ships to the trees instead of putting down the Anchor.’ [17]

This aspect of Sydney’s waterfront – deep water alongside natural rock shelves – was often mentioned by visitors in the years before Circular Quay was built. In 1802, for example, the French explorer, Francois Peron, wrote of Sydney Cove:

‘The natural quays are so perpendicular and well formed that, without any kind of labour or expense on the part of the English, the largest ships might be laid along them with perfect security.’ [18]

Given this topography, it seems likely that on the 26th of January, Phillip would have selected one of those places where the ships’ boats could be laid alongside the rocks to offload their people and cargoes.

Layout of the Settlement

It is also helpful to understand the broad layout of the early settlement. Phillip had probably done some basic planning when he visited the cove on the 22nd, but he would have refined his decisions when he went ashore again on the morning of the 26th. The settlement was divided by the stream, and until a wooden bridge was installed in October 1788 (close to the intersection of Pitt and Bridge Streets today), residents had to walk up to a spring (close to the present intersection of Pitt and Spring Streets) to make their way across to ‘the other side of the water’.

The Governor, the civil officers and other gentlemen were concentrated on the east side, clustered around the Governor’s garden and a pre-fabricated house that had been shipped out for his use. The convicts and marines, and the hospital and storehouses, were on the west, although there were a small number of convicts housed over near the gentlemen.

The marine quarters were located at the southern end of a track that ran along the west side (close to the intersection of George and Grosvenor Streets today). As noted above, the 26th was spent clearing the trees and undergrowth from this site, so the marines could spend that first night on shore. Since no work was done on the east side of the stream that day, a west-side landing would have been more practical.

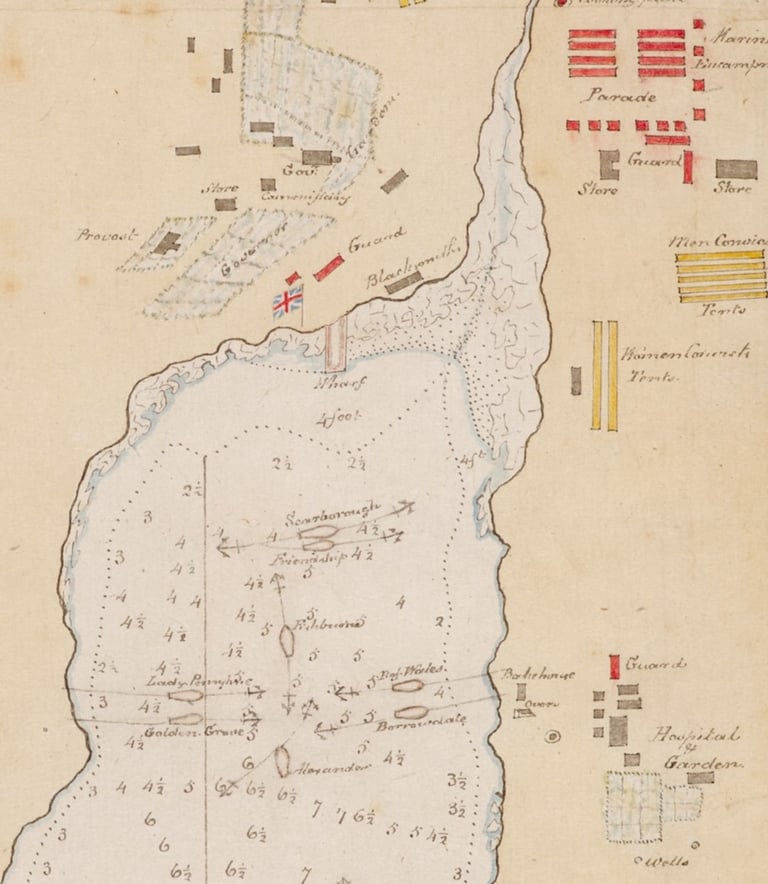

At 4 o’clock the next morning, the largest of the transports, the Alexander, ‘warped into the Cove, close to the Landing place, moored the ship head & stern. . .’[19] A map showing the location of the ships that morning depicts her (and thus the landing place) halfway along the cove, at some distance from the mouth of the stream.

Detail of William Dawes, 'Sketch of Sydney Cove, Port Jackson, July 1788 [9]

Vaucluse Bay, 1999 [11]

Since there was already a landing place on the west side by 4am on the morning of the 27th, it must have been identified the day before.

Case for the West Side

Based on an account of these events written by David Collins, Phillip’s official secretary (who was not present that day), it is generally accepted that the flag-raising ceremony was held close to the place where they had come ashore.

‘In the evening of this day the whole of the party that came round in the Supply were assembled at the point where they had first landed in the morning, and on which a flag-staff had been purposely erected and an union jack displayed, when the marines fired several vollies; between which the governor and the officers who accompanied him drank the healths of his Majesty and the Royal Family, and success to the new colony. . .’ [21]

It follows that any evidence about the site of the ceremony will give a rough idea about the location of the landing.

Eyewitness Accounts

There are two accounts of what happened that day attributed to known eyewitnesses. The first is from the Voyage to Botany Bay (1789), which is based in part on Phillip’s official dispatches:

‘The debarkation was now made at Sydney Cove, and the work of clearing the ground for the encampment, as well as for the storehouses and other buildings, was begun without loss of time. . . In the evening of the 26th the colours were displayed on shore, and the Governor, with several of his principal officers and others, assembled round the flag-staff, drank the king's health, and success to the settlement.’ [22]

Phillip’s dispatches don’t include any description of the landing or the ceremony, and it is possible that these words were written by Collins in his capacity as the Governor’s secretary.

The only confirmed account was written by Lieutenant Philip Gidley King, Phillip’s aide-de-camp: he left three versions, the fullest of which is found in the so-called ‘Fair Copy’ of his journal:

‘At day light the Marines & Convicts were landed from the Supply & the latter began clearing away a piece of Ground to erect the tents on, after noon the Union Jack was hoisted on shore & the Marines being drawn up under it, The Governor & officers to the right & the Convicts to the left. Their Majesties & the Prince of Wales health, with success to the Colony was drank in four glasses of Porter, after which a feu-de-joi was fired & the whole gave three Cheers, which ceremony was also observed on board the Supply.’ [23]

Neither Phillip’s Voyage nor King’s journals say where the landing or the flag-raising ceremony occurred.

Another First Fleet Account

There is another contemporary account by a First Fleeter, the significance of which was overlooked until 2010 when Michael Flynn discovered it in the State Library of NSW (although it had been published in a regional newspaper in 1852). This is from a letter written in April 1789 by John Campbell, a seaman on one of the transports, on the voyage back to England:

‘the Governor went on Shore to take Possession of the Land with a Company of Granadeers & Some Convicts At three A Clock in the Afternoon he sent on board of the Supply Brigantine for the Union Jack then orders was Gave fore the Soldiers to March down to the West Sid of the Cove they Cut one of the Trees Down & fixt as flag Staf & Histd the Jack and Fired four Folleys of Small Arms which was Answered with three Cheers from the Brig then thay Marched up the head of the Cove where they Piched their Tents.’ [24]

We don’t know that Campbell was on shore that day, but if he wasn’t, this is still, by some years, one of the earliest second-hand accounts. It locates the site of the flag-raising on the west side and at some distance from the marine encampment.

Location of the Landing on the 22nd

Another way of establishing where Phillip might have gone ashore on the 26th of January lies in determining where he landed on the 22nd when he first visited the cove: if the landing place that day was convenient, then he would have been inclined to use it again on the 26th. In this case, we do have a description of the location by an eyewitness – Jacob Nagle, a crew member in Phillip’s boat:

‘[We] landed at the West Side of the cove along Shore was all Bushes but a small distance at the head of the Cove was level & large trees & no under wood worth mentioning & a Run of fresh water Runing down into the Center of the Cove. The Governer & Officers & and Seamen Went up to Seet it.’ [25]

Tradition: A Site Behind Cadman’s Cottage

Throughout the entirety of the nineteenth century, the site of the flag-raising was associated with a specific location in George Street today behind Cadman’s Cottage (one of the oldest buildings in NSW, which stands close to the shoreline on the west side).

Howe’s 1806 Almanack: The first published work to identify this site appeared in 1806, 18 years after the events in question, when the Government Printer, George Howe, issued his New South Wales Pocket Almanack.

Ken Knight's interpretation of the landing place on the morning of 26 January

The flagstaff in Loftus Street, behind Circular Quay

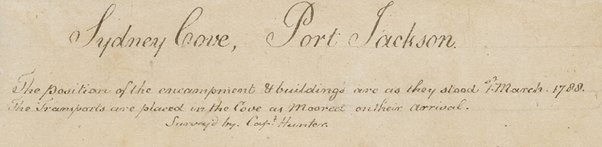

Detail of William Bradley, ‘Sydney Cove, Port Jackson’, '. . .The Transports are placed in the Cove as Moored on their arrival. Survey’d by Capt. Hunter’.[20]

Howe included a brief history of the colony, with the following passage under the heading of 26 January 1788:

‘British colours hoisted on the north point of the present dock yard, and possession taken by Gov. Phillip, lieuts. Ball and King of the Royal Navy, and lieuts. Johnston, Collins, and Dawes of Marines.’ [26]

The dockyard in question was on the west side of the cove, just to the south-west of Cadman’s Cottage. The names of the officers he lists as being onshore that day are correct, although they were not established from other sources until a century later. This means that Howe’s account must have come, directly or indirectly, from someone who was present. The Governor of the colony in 1806 was Philip Gidley King.

Removal of the Swamp Oak (1832): For many years, a swamp oak stood in the footpath close to the corner of the dockyard – it can be seen in sketches and paintings of the high street (now George Street) from the middle of the 1790s. Rightly or wrongly, it came to be associated with the flag-raising, and when it was pulled down in 1832, there was a public outcry. The Sydney Herald reported:

‘A swamp oak at the lower end of George-street, near the Dock-yard, upon which the British flag was first hoisted in the town, has been lately cut down by the gang employed in repairing the streets. The tree was considered sacred by Governor Macquarie, and the old hands of the Colony.’ [27]

Some of the ‘old hands’ acquired pieces of the wood ‘for the purpose of having it manufactured into snuff boxes’.[28] In our view, this tree was too small and bushy in 1788 to have been used as a flagstaff, but we acknowledge that there was a strong tradition associating this site with the ceremony.

Detail of Thomas Watling (att.), ‘View of Sydney’, 1795-96, showing the tree in front of the surgeon’s house in what is now George Street [29]

Stories of a First Fleeter (1840s): When the First Fleet convict, John Limeburner, died in 1847, an obituary recalled that he had told a number of people over the years that he ‘remembered the British Flag being first hoisted in Sydney on a swamp-oak tree, which was placed in the spot, at the rear of Cadman’s house’.[30]

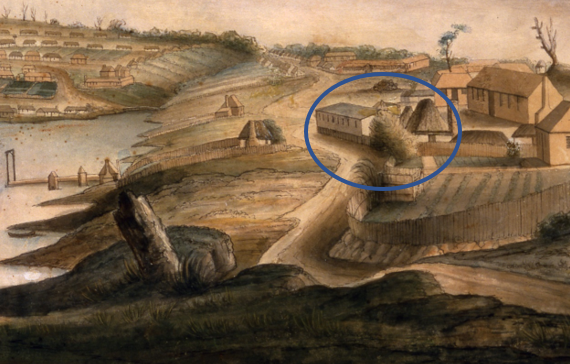

A Mid-19th Century Inscription: A painting of the west side made in the mid-1790s has an inscription on the reverse which reads as follows:

‘This drawing was made by Admiral Hunter second Governor of New South Wales AD 1793. The old gum tree first carried the King’s flag hoisted by Governor Phillips. The frigate “Sirius” was afterwds wrecked on Norfolk Island.’

John Hunter (att.), ‘View of Sydney Cove, 1793’, c.1795 [31]

The old gum tree is at the left of the painting: it was located on top of the ridge at the northern end of the high street, close to the site of the Mariners’ Church today. It appears in several early paintings and seems to have been something of a landmark. This site was around 50 to 100 metres from the corner of the dockyard – the swamp oak that was also associated with the flag-raising can be seen along the high street in the middle distance (circled in blue).

The attribution to John Hunter is no longer accepted, but in comparing the infrastructure along the cove with other early paintings, it would seem that this painting was made in 1794-95. It was apparently owned by Hunter and passed down through his family, who brought it to Australia in the late 1830s.

The inscription was added after 1807 when Hunter was promoted to Admiral, but before 1854 when it was quoted in a newspaper article which described the painting.[32]

Dawes Point: In 1831, an emancipist surgeon, Thomas Parmeter, claimed the flag had been raised at Dawes Point. This theory briefly resurfaced several times in later decades, the confusion probably arising because the east-side flagstaff was moved there in 1791. Parmeter had only arrived in 1816 and had perhaps heard the stories of a west-side ceremony.[33]

Memoirs of an 1821 Arrival: Towards the end of his life, John Bingle, one of the founding fathers of Newcastle (the city in NSW), wrote a memoir in which he recalled his arrival in Sydney in December 1821:

‘There was an old tree left standing as a monument in George Street opposite the dockyard wall when I arrived, and it remained standing for some years after and Governor Phillip stood under it on the 26th January 1788 and named the adjoining water Sydney Cove. A flagstaff was erected close to it on which ‘the flag that braved a thousand years the battle and the breeze’ was unfurled and the King’s health drunk with all the honours by the Governor and all his officers.’ [34]

Memoirs of an 1820s Childhood: Thomas Brennan, the son of an Irish convict, was raised by the Naval Officer, Captain John Piper, whose Sydney home and office stood on the ridge where the Mariners’ Church was later built. Piper’s father-in-law, a First Fleet convict, also lived with the family. In 1882, Brennan wrote an account of life in early Sydney, which included a recollection of the tree near the dockyard wall:

‘In North George Street stood a large she oak tree, nearly opposite Argyle-street, and about two feet from the old dockyard wall, where, it was said, the first flag was hoisted when the country was taken possession of. When a boy, I and other boys often climbed up the oak tree. It was a pity it was cut down, as it was only two feet from the dockyard wall in George-street, and would have been a relic of olden times.’ [35]

Memoirs of the Landing Place

At the turn of the century, two old-timers wrote down stories they had heard about the place of landing. Given that they were recorded more than a century later, these stories must be treated with great caution, but in both cases, there are reasons for according them some respect.

Richard Kemp lived in George Street, opposite Captain Piper’s house in the 1820s. From 1897 until 1904, he claimed on several occasions that the landing had taken place at a small beach below the ridge on which the Naval Officer’s house stood (now the site of the Mariner’s Church), where he used to swim as a boy. His source was a local resident whose family had a First Fleeter living with them.

'Adjoining Mr Campbell’s was the residence of Captain Piper, superintendent of H.M. Dockyard, a most unsightly, unpainted building. The Mariner’s Church now occupies its site. The land rose very sharply just here, but fell towards the south end, where the road now is. At the southern extremity a rock set on its edge ran out from 20ft. to 25ft. in a north-easterly direction, the outer end being 10ft. to 12ft. high, decreasing towards the land where it was about 4ft. Behind or rather inside this rock was a little cove or bay with a clean sandy beach, and here, as I understood, the first white man jumped ashore when the fleet came round from Botany Bay.' [36]

‘Old Chum’: For many years, J.M. Forde wrote reminiscences of old Sydney for the newspapers under the pseudonym ‘Old Chum’. In 1912, he recalled that 40 years before, an ‘old hand’ had shown him a piece of rock which he claimed had come from the spot where Phillip had stepped ashore. Forde said that he had seen ‘that boulder blown up by engineers improving Circular Quay’.[37]

This story acquires some credibility when we know that in 1875, around 40 years prior to the date this story was published, a large rock on the western side of the cove was blasted in order to make way for an extension of the quay. The ‘old hand’ seems to have kept one of the fragments as a memento.[38]

Case for the East Side

By contrast, there are no First Fleet records referring to an east-side landing, no stories told by First Fleeters that were written down by men and women who personally heard them, and until 1848, no evidence that anyone claimed Phillip had landed on the east.

Tradition: The Obelisk in Macquarie Place

The first time that an east-side location was mentioned was 60 years after the event, when a Sydney guidebook identified the flagstaff with the obelisk in Macquarie Place:

‘On the 26th January (a sufficient space for the military and convicts to encamp upon having been previously cleared) they were all landed near where the obelisk now stands, and the national flag was hoisted.’ [39]

The author, Joseph Fowles, offered no evidence, although another guide three years later insisted that there was a tradition linking the ceremony to this site, ‘and we see no reason to doubt its truth’. [40] To date, no evidence has been found of such a tradition prior to 1848. Fowles had been living in NSW for ten years when he first published his guide.

From 1900, the obelisk became an obsession with some of the east-side advocates, particularly Albert Lee’s wife, Minnie, who in 1907 convinced the Women’s Branch of the Empire League to erect a flagstaff nearby. It was 80’ (24 metres) high and the flag was 24’ (7.3 metres) long, the largest in Sydney.[41]

That same year, a cannon and an anchor from HMS Sirius, recovered from the wreck off Norfolk Island, were deposited in Macquarie Place, again because of this association with the obelisk.[42]

By the 1920s, Mrs Lee had become obsessive: to her, there was no question that the obelisk was erected to mark the site of the ceremony, and that Governor Macquarie, who commissioned the structure, had buried papers inside which the government must disinter.[43]

This is all hogwash. We now have Macquarie’s journal note for the day he ordered the construction of the obelisk, which makes absolutely clear what he was thinking:

'Thursday 19. Septr. 1816: I have this day contracted with Edward Cureton, Stone Mason, to erect a very handsome Stone Obelisk in the Center of Macquarie Place, as an Ornament to this Part of the Town, and also for the purpose of measuring the miles from to all the interior parts of the Colony. . .' [44]

Macquarie Place was Sydney’s first designed public square, and the obelisk was installed in its heart for the same reason that they were placed at the centre of parks throughout Europe – in imitation of the ancient piazzas of Rome.

The Hunter Drawing (August 1788)

In his 1900 booklet and subsequent missives to the papers, Alfred Lee relied heavily on a sketch of the cove made on the 20th of August 1788 by John Hunter, second captain of HMS Sirius, which showed a flagstaff close to the beach on the eastern side of the stream.[45] He never fully explained why he associated this flagstaff with a ceremony held seven months earlier, but his reasoning appears to have been as follows:

· There were no other drawings from 1788 showing a flagstaff anywhere else in the cove.

This is correct, although Hunter’s drawing, which survives as an engraving and a watercolour copy by Lieutenant William Bradley, is the only known illustration of any part of the cove until 1791. The earliest known portrayal of the west side of the cove dates from 1792 or 1793.

· There was no documentary evidence associating a flagstaff with the Mariner’s Church site on the west side (nominated by some of the west-side advocates as the landing place).

In 1900, Lee was unaware of the long tradition associating the flag-raising with the site in George Street just to the south of the Mariner’s Church, and when the 1806 almanac was rediscovered in 1918, he dismissed it as a mistake on the editor’s part.

· The original sources stated that ‘the landing on the 26th took place well towards the head of Sydney Cove, on the east side. . .’

This is discussed separately below, but none of the sources say that the landing took place at or near the head of the cove.

· Phillip began clearing the site for his temporary accommodation on the 26th of January. This was to become the administrative heart of the settlement, close to the site of east-side flagstaff drawn by Hunter, so the flag-raising ceremony must have been held there.

Phillip’s house did become the administrative centre of the settlement, but as discussed above, there is no evidence that any work was done on the east side on the 26th, in which case Lee’s conclusion is wrong.

· Whilst never stated explicitly, Lee assumed that the ceremony on the 26th would not have been a makeshift affair: it must have been held at a site of significance to the future settlement.

Flags were used for a variety of purposes – signals, ceremonies and coordinates – and there is no evidence that Phillip was averse to the use of temporary flagstaffs. The colours were raised at the swearing-in ceremony held on the 7th of February, adjacent to the marine parade ground on the west side.[46] And, as noted above, the evidence suggests that the flag-raising on the afternoon of the 26th of January was hastily organised.

· The first celebration of the original landing and flag-raising was held on 26 January 1791 at the east side flagstaff.

This is correct, and several other official ceremonies (such as the celebration of royal birthdays) had taken place there since August 1788. By 1791, this site did have vice-regal significance, but these later ceremonies are not evidence of what happened on the 26th.

While Alfred and Minnie Lee and their followers (who included significant NSW historians of the time such as Frank Murcott Bladen and Frank Walker) were adamant about an east-side landing, their arguments were not well founded even then, and they have been further weakened by evidence that has come to light in recent years.

‘The Head of the Cove’

A number of writers have assumed that if Phillip landed at the head of the cove, then the ceremony must have been somewhere close by – along the southern waterfront where Circular Quay now stands (or rather behind the quay, since the waterfront was shifted out with its construction).[47] No one has ever argued for a landing on the west bank of the stream.

However, none of the original sources say that they landed at the head of the cove – what they actually say is that the settlement was established there, and Campbell specifically states that the new arrivals moved between the landing place/site of the flag-raising (on the west side) and the head of the cove, indicating these were some distance apart.[48]

In any case, the ‘head of the cove’ did not lie at the southern end of the inlet, but part way up the stream, close to the intersection of Pitt and Bridge Streets today.[49] Given the shape of the cove in 1788, no one at that time would have regarded a flagstaff on the shore to the east side of the stream as standing at the head of the cove.

Bradley’s Journal and Chart

In 1924, the State Library of NSW acquired a journal by Lieutenant William Bradley, along with his watercolour copy of Hunter’s drawing of 20 August 1788, and a number of charts, one of which purported to show Sydney Cove on 1 March 1788. Bradley’s map included a flagstaff on the east side, which seemed to shift the date of its erection back to some date prior to March, and the journal included an entry for 6 February with the coordinates of a flagstaff.[50]

Minnie Lee immediately recognised the significance of this, and east-side advocates involved with the committee established by the Sydney City Council in 1963 (on which, see below) argued that this flagstaff must already have been in place when Hunter and Bradley left for their surveying expedition of the harbour on the 28th of January.[51] This brought them to within two days of the landing, and while they acknowledged that they were unable to close this gap, they felt that was close enough.

The recently retired NSW Surveyor General was a member of the committee and used Bradley’s coordinates to identify the site in Loftus Street where the flagstaff stands today. The Bradley material demands some discussion.

Dating: The journal, charts and the watercolour are not originals: they are fair copies produced by Bradley at some point after 1802 (the date of the watermarks on the paper). A copy of his ship’s log, acquired by the Australian National Maritime Museum in 2018, it is also a fair copy made after 1802.[52] The two documents are not directly related to one another – evidently, Bradley was keeping a daily journal in narrative form at the same time as he was writing up his own version of the log.

The Chart: Bradley acknowledged that his chart of Sydney Cove was a composite of two dates more than a month apart – the ships were shown in the moorings they had taken up on the 27th of January, while the encampments and the buildings were as they were on the 1st of March.

Heading of Bradley’s Chart of Sydney Cove [53]

However, the chart is more complex than this. Some of the infrastructure shown as completed was in an early stage of construction on the 1st of March: the most notable examples are the Governor’s Wharf, where work had only just begun, and the observatory on the western point of the cove, which was still a long way from finished. To some extent, Bradley was showing the settlement as it would become later in the year.

And there are two charts of the cove produced after the 1st of March which do not show the flagstaff. Francis Fowkes’ rough sketch, dated to 16 April, does not include it, but it is such a crude representation that its absence is explainable. On the other hand, Dawes’ plan of the settlement, made in May and June, was carefully drawn, with the intention of sending it to the Home Secretary, and it does not portray the flagstaff either. Its inclusion in Hunter’s drawing of the 20th of August confirms that it had been installed by that date, and the next (known) chart of the cove, dated to October of that year, also shows it. In short, Bradley’s 1802 chart of Sydney Cove is not the unassailable proof that the east-side advocates had hoped.

The Journal: His journal entry for the 6th of February is perhaps better evidence, but not without its own difficulties. Contrary to what some east-siders have argued, the flagstaff was not used as the base for establishing the coordinates for Hunter’s survey of the harbour. Bradley provided only one set of calculations for it, and two for the observatory on the western point of the cove. The other officers trying to establish the latitude and longitude of the settlement, Captain Hunter and Lieutenant Dawes, had no interest in the flagstaff, and left no coordinates.

All three men invested a great deal of time in trying to ascertain longitude because the chronometer had run down at sea, but these readings were made at the observatory and on board the Sirius which was anchored just outside the cove. And because the timekeeper had ceased to keep Greenwich Mean Time, Bradley’s longitude estimate for the flagstaff is wildly inaccurate, lying some miles out to sea. It is impossible to compensate for this error today, so the Surveyor-General’s seemingly precise conclusion as to the location of the east-side flagstaff was a guess.

Latitudes established by a modern sextant are typically accurate to within around 800 metres, although they are capable of accuracy to within 200: mariners such as Bradley and Hunter would compensate by taking a number of readings and average them. There are four different sets of coordinates for the observatory by Hunter, Bradley and Dawes, and they range from 33º 51’ 18” to 33º 51’ 50”, a difference of around 420 metres. Once again, the Surveyor-General’s conclusions about the site of the east-side flagstaff are highly suspect.

It is possible there was a flagstaff on the eastern side of the stream as early as the 6th of February, but we cannot be sure. Given the margin of error, it is also possible that the flagstaff mentioned by Bradley was on the west side of the cove, erected for the swearing-in ceremony which was to be held the following morning. But if there was already a flagstaff on the east side, Phillip did not regard it as sacrosanct, since the colours were also flown on the west side the next day.

The Johnston Family

The only known tradition of an east-side landing comes from the family of George Johnston, the marine lieutenant who was (possibly) the first British officer on shore on the 26th of January.

Johnston told a court in 1811: ‘In 1786 I volunteered to New South Wales, and was the first officer who landed there’.[54] He was not the first man ashore in Botany Bay, so he was either saying that he was the first to land in Port Jackson on the 21st of January or (more likely) in Sydney Cove on the morning of the 26th.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, George Johnston’s great grandson, Douglas Hope Johnston, promoted a variety of stories about his illustrious ancestor – that he was ‘the first British military officer to land in Port Jackson’[55]; that he was ‘the only officer who accompanied Governor Phillip on his famous voyage with three boats’ when they discovered Port Jackson and selected Sydney Cove as the site for settlement[56]; that he was the first man ashore in Manly Cove on that expedition.[57]

Hope Johnston fervently believed his great grandfather was present on the 22nd of January when Phillip selected the site for the settlement, and in 1926, he commissioned a painting by John Allcot, ‘The Discovery and Fixing of the Site of Sydney’, which included George Johnston. He also described in some detail what happened that morning and claimed to know precisely where (on the west side) they were standing when the decision was taken:

‘The group are standing at a spot behind where is now the New Zealand Insurance Co’s building a little above Bridge street on the George street side of Hamilton street down which the stream of fresh water then ran.’ [58]

Other than Nagle, there are no accounts of Phillip’s first visit to the cove, and this painting and the details provided by Hope Johnston were his own imaginings (or perhaps those of some other family member). There is no evidence that George Johnston accompanied Phillip on this first visit to the cove, and a source from the ship on which he sailed states that he was first given orders to join Phillip on the 24th.[59]

Lieutenant Johnston was with Phillip in the Supply on the 25th. But in one of his many private papers, Hope Johnston claimed that his great grandfather went ashore that same afternoon, and that on the 26th, he landed with convicts and marines several hours ahead of Phillip. There are no sources which support either of these claims, and some to the contrary.[60]

In 1963, the Sydney journalist and amateur historian Malcolm Ellis wrote that many years before, Hope Johnston had shown him the spot on the east side where family tradition said that Lieutenant Johnston (and Phillip) had landed. Hope Johnston said that this spot had been pointed out to him by his father, who been shown it by his father, Captain Robert Johnston (George Johnston’s eldest surviving son).[viii] In private papers, he also claimed that Robert Johnston had told his grandchildren in the 1840s, that when his father (George Johnston):

‘. . . jumped out of the boat. . . [near the Tank] stream he mistook the depth, and as he was doubled up water went over his head, his hat floated off and all the officers laughed as did the men as he waded ashore, onto a small patch of about thirty feet of sand.’[61]

Hope Johnston proudly observed on numerous occasions that his great grandfather had been present on the evening of the 26th, in one article adding that Phillip had personally given him the order to raise the flag. This is another family tradition which cannot be directly challenged, but other aspects of his story can. He claimed, for example, that the ceremony took place at around 7pm, when King placed the flag-raising at 2pm and Campbell around 3.[62] (The Collins family also had a tradition that Lieutenant William Collins – brother of David Collins, who was present on the 26th – ‘unfurled the first British flag at Sidney Cove’.[63])

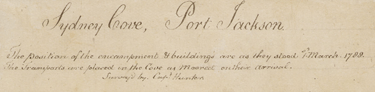

Douglas Hope Johnston was immensely proud of his great grandfather, and in 1936, he commissioned the British artist, Algernon Talmage, to capture the flag-raising ceremony in oil, resulting in the well-known painting, ‘The Founding of Australia’. Hope Johnson did all the research, and consistent with his personal beliefs, the painting shows the ceremony being held on the eastern side of the stream. (In this version, he has a sailor raising the flag, not a marine.)

Algernon Talmage, ‘The Founding of Australia, 1788’ [65]

The Johnston family stories are important historical anecdotes that deserve to be better known, but they must be weighed against the rest of the evidence. They are part of an oral tradition, not recorded until 140 to 175 years after the event by individuals three or four times removed from the original source.

The Herron Committee (1963)

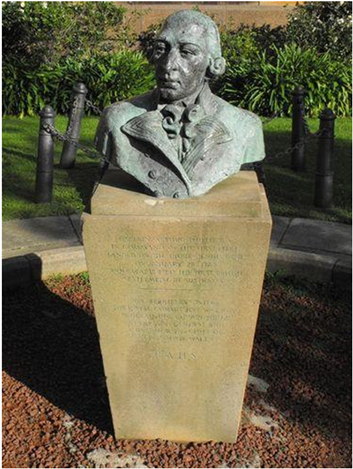

In the early 1960s, the west side was still dominant. A bust of Arthur Phillip donated by the businessman and philanthropist, Sir Edward Hallstrom, was installed in front of the Maritime Services Building (now the Museum of Contemporary Art), on the west side of Circular Quay, in 1954. The site was selected by the Maritime Services Board and the Royal Australian Historical Society (RAHS), although the inscription avoided making a commitment as to the place of landing.

Jean Hill. 'Captain Arthur Phillip', c.1953, when it stood in front of the Maritime Services Building

Following the completion of the Overseas Passenger Terminal in 1960, the Maritime Services Board commissioned Arthur Murch to paint a mural: this building stands in front of the Mariner’s Church, where west-side advocates had long maintained that Phillip had landed. In some respects, the mural is symbolic, but it does feature the flag-raising. The description in the State Heritage Inventory states that the mural was located ‘near the landing place of Captain Phillip’. Research for the Maritime Services Board was undertaken by John Earnshaw on behalf of the RAHS.[66]

Arthur Murch, ‘The Foundation of European Settlement’, Mural in oil, North Wall of the Overseas Passenger Terminal, Sydney

In February 1963, the then Lord Mayor of Sydney proposed the installation of 100 markers around the city identifying early historic sites. The RAHS was approached to do the research, and a committee was duly established. As originally proposed, Item 1 was ‘The Foundation Tree’, to be located at ‘Rear of Cadman’s Cottage on the eastern side of George Street north’, with the following explanatory note:

‘Near this spot, until 1832, was preserved a large she oak under which, it is recorded, Governor Phillip held on Jan. 26, 1788, a ceremony which marked the foundation of British settlement in Australia.’ [67]

A marker was installed at the site, but before a plaque could be added, a group of east-side advocates based out of the Australasian Pioneers Club, launched a campaign to stop it. Douglas Hope Johnston had been one of the founders of the club, and in 1963, the secretary and the chair of its historical committee was Malcolm Ellis, a Hope Johnston acolyte and avowed east-sider. Ellis worked closely with Alderman David Griffin, another active member of the club and east-sider, who pushed for the council to establish a committee to investigate the question.

The committee was chaired by the then Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Sir Leslie Herron (with the Lord Mayor as his alternate), the retiring Surveyor General of NSW, the Sydney City Council’s director of parks, and John Forsyth, a lawyer and amateur historian.

Herron took no active part in the work of the committee, and Forsyth was the only member with any interest or expertise in historical research. He was a close confidant of Malcolm Ellis, and yet another east-sider. The committee did not employ a professional historian to undertake its research, relying exclusively on Forsyth’s work. There was no call for public submissions. Malcolm Ellis submitted a paper, although he also lobbied the Chief Justice direct and ran a public campaign in the press. The RAHS declined to take a position, although John Earnshaw did make a personal submission arguing the case for a west-side landing.

Unsurprisingly, the committee arrived at the conclusion that the ceremony had been held on the east side. The now-retired Surveyor General claimed that he had been able to establish precisely where the flagstaff had stood, and a replica with an explanatory plaque was installed on the site in 1967, closing down the debate for four and a half decades.

The Landing Place

The weight of evidence now points to the flag-raising ceremony having taken place on the western side of the cove, just to the south-west of where Cadman’s Cottage stands today, although it is possible that it was held on the top of the ridge where the Mariner’s Church now stands. It is impossible to be more precise. We think it unlikely that a living tree was used – more likely, the trunk of a young straight tree was cut down and erected as an improvised flagpole.

There is some evidence indicating that Phillip and his party landed on a little sandy beach on what is now reclaimed land near the bottom of the Bethel Steps, behind the Overseas Passenger Terminal, about 100m to the north of Cadman’s Cottage.

Phillip would have chosen the west side because that was where he had landed on the 22nd, and because his primary focus on the 26th and the days that followed was in getting the convicts and marines ashore. He had been impressed by the rock platforms, ‘quite perpendicular & perfectly flat at top’, which were ideal for loading and unloading the largest ships’.

Vessels were able to moor so close to the rocks at this site below where the Mariner’s Church was later built that crew members could walk ashore on gangplanks.[68] This part of the cove was visually striking, with a large rock in the water just offshore that was known to First Fleeters as ‘Reed’s Rock’, named after the carpenter of the Supply.[69]

There appears to have been a narrow path between the rocks leading from the waterfront up to the track which ran along the western side of the cove to the convict and marine camps, and the storehouses (lower George Street today). This path would later be widened and named Bethel Street (since built over).

In Summary

Too often, the history of European Australia is presented as an unchanging (and unchallengeable) tableau of received interpretations, entrenched ideas and uninspiring themes, infused with the sense that European settlement is too recent to have a proper history and that, in any case, it has all been done.

Historical research can also be dynamic, our understanding changing and adapting as new information comes to light, an empirical discipline based in scientific curiosity, weighing and testing evidence, drawing wherever possible from original sources, attempting to locate people and events in time and space. Interpretation and inference are necessary, but speculation must be grounded in the best information available, open to revision as new evidence is found. As the Greek historian, Thucydides, wrote:

So little trouble do men take in the search after truth; so readily do they accept whatever comes first to hand. . . At such a distance of time [the historian] must make up his mind to be satisfied with conclusions resting upon the clearest evidence which can be had.

Research Notes

Gary Sturgess developed an interest in this question in 2011 when, on his return after 10 years in London, he asked Wayne Johnson, then the archaeologist at the Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority (SHFA) to walk him around the settlement as it was in 1788. While standing on the Bethel Steps, behind the Overseas Passenger Terminal, Johnson pointed out a plaque, installed by SHFA, which states that Phillip landed close to that spot.

Around the same time, Michael Flynn began to take an interest in the question, after discovering the Campbell letter in the State Library.

Since then, we have tracked down all known original sources (documents, drawings and charts) from 1788 until after the extension of Circular Quay along the west side of the cove in the mid-19th century, as well as all significant secondary sources.

______________

Endnotes

The illustration on the cover page of this newsletter is interpretation of the landing place as it would have looked on the morning of the 26th of January, by the Australian artist Ken Knight in 2015. Original in possession of Gary L. Sturgess.

[1] Britt Zerbe, The Birth of the Royal Marines, 1664-1802, Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2013, p.192; J. Bartrum, A Charge of Mutiny, London: Sherwood, Neely & Jones, 1811.

[2] The ‘Prince of Wales Source’ in Morning Chronicle & London Advertiser, 27 March 1789; George B. Worgan, Journal of a First Fleet Surgeon, Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1978, p. 36.

[3] The ‘Prince of Wales Source’, Morning Chronicle & London Advertiser, 27 March 1789; David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [1798], Sydney: A.H. & A.W. Reed, 1975, Vol.1, p. 4.

[4] Writers who have claimed a single ceremony in the morning – Jonathan King, The First Fleet, London: Secker & Warburg, 1982, p. 166; David Hill, 1788: The Brutal Truth of the First Fleet, North Sydney: William Heinemann, 2008, p. 148; Nadia Wheatley, Australians All, Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2013, p. 56.

Writers who claimed two ceremonies, one in the morning and one in the afternoon – Alan Frost, Arthur Phillip, 1738-1814: His Voyaging, Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1987, pp. 166-167; Louise Anemaat, ‘Flagging Memory’, SL Magazine, State Library of NSW, Summer 2014-15, p. 35; Ann Moyal, ‘Arthur Phillip: 1788. The Foundation Year’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, adb.anu.edu.au/essay/21.

All of these writers were influenced by the suggestion of Fidlon and Ryan, when they edited the so-called ‘Private Journal’ of Philip Gidley King for publication, that it was the original - ‘Editors’ Preface’, Paul G. Fidlon and R.J. Ryan (eds.), The Journal of Philip Gidley King: Lieutenant, R.N. 1787-1790, Sydney: Australian Documents Library, 1980, p. v.

The Private Journal seemed to indicate that there was only a morning ceremony, while the so-called Fair Copy referred to an afternoon ceremony. No other source refers to a ceremony in the morning. The recent discovery in the Royal Collections at Windsor of a third version of King’s journal, based on his original ship’s log, makes it clear that the Private Journal is not the original, that the wording appears to indicate a morning ceremony because of the omission of a number of words in transcription, and that the flag-raising occurred shortly after 2pm.

[5] In his letter about the ceremony, the First Fleet seaman, John Campbell wrote ‘At three A clock in the Afternoon he sent on board of the Supply Brigantine for the Union Jack. . .’ – John Campbell to his parents, 9 August 1789, State Library of NSW (hereafter SLNSW), ML MSS 7525.

[6] Alfred Lee, ‘The Landing of Governor Phillip in Port Jackson’, The Australian Historical Society Journal and Proceedings, 1901, Vol.1, Part 1, pp. 2-3; Frank Murcott Bladen to the editor of the Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney Morning Herald, 19 September 1902, p. 3; Minnie Lee to the editor of the Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 January 1904, p. 5.

[7] Draft of Sydney to Phillip, 20 April 1787, UK National Archives (hereafter TNA) CO201/2/135.

[8] John Campbell to his parents, SLNSW, MLMSS 7525.

[9] ‘Sketch of Sydney Cove, Port Jackson, in the county of Cumberland. Showing temporary buildings in black and permanent buildings proposed and now erecting in red’, TNA MPG 1/300, enclosure to a despatch from Governor Phillip, extracted from TNA CO201/2.

[10] D. Benson and J. Howell, Taken for Granted: The Bushland of Sydney and its Suburbs, Sydney: Kangaroo Press, 1990, p.43.

[11] NSW Land & Property Information, detail of NSW 4500, Run 3, Print No.62. Used with permission.

[12] Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘Journal of Arthur Bowes Smyth, 22 March 1787 to 8 August 1789’, National Library of Australia (hereafter NLA) MS4568, 10 March 1788.

[13] Colnett to Nepean, 14 September 1803, TNA ADM1/1635/432.

[14] Sydney Gazette, 10 July 1803, p.2.

[15] Jacob Nagle, ‘Jacob Nagle his Book A.D. One Thousand Eight Hundred and Twenty Nine May 19th. Canton. Stark County Ohio’, comp. 1829, SLNSW, ML MSS 5954, p.83

[16] Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘Journal of Arthur Bowes Smyth, 22 March 1787 to 8 August 1789’, NLA MS4568, 23 January 1788.

[17] Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘Journal of Arthur Bowes Smyth’, ibid. In spite of the date in Smyth’s diary, this entry was clearly made on the 27th.

[18] Francois Peron, A Voyage of Discovery to the Southern Hemisphere, London: Richard Phillips, 1809, Chapter 20.

[19] Log of the Alexander, 27 January 1788, TNA ADM51/4375.

[20] SLNSW, Safe 1/14.

[21] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [1798], Sydney: A.H. & A.W. Reed, 1975, Vol.1, pp. 4-5.

[22] [Anonymous], The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay, London: John Stockdale, 1788, pp. 57-58.

[23] Philip Gidley King, ‘Fair Copy of Remarks & Journal Kept on the Expedition to form a Colony. . .’, comp.1790, SLNSW Safe C115.

[24] John Campbell to his parents, 9 April 1789, SLNSW MLMSS 7525.

[25] Jacob Nagle, ‘Jacob Nagle his Book. . .’ op. cit., p. 83.

[26] G. Howe (comp.), New South Wales Pocket Almanack and Colonial Remembrancer for 1806, Sydney: Government Printer, p. 25.

[27] Sydney Herald, 7 May 1832, p. 3.

[28] Sydney Herald, 28 May 1832, p. 3. See also Hill’s Life in New South Wales, 6 July 1832, p. 4; E.W. O’Shaughnessey (comp.), Australian Almanack and General Directory for 1835, Sydney, 1835, p. 60. There was one report that the trunk of this tree was still standing in 1864 – Sydney Morning Herald, 27 January 1864, p. 5.

[29] SLNSW, Mitchell Library, V1/1794 + /1.

[30] Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer, 11 September 1847, p. 2.

[31] State Library of Victoria, La Trobe Collection, H5231. The library has no information as to the provenance of this painting. It was entered into the accession register in the early 1930s, but a great deal of retrospective accessioning went on at that time, and it was probably acquired much earlier – telephone communication between Gerard Hayes and Gary Sturgess, 15 March 2012.

[32] Argus, 18 September 1854, p. 5.

[33] ‘De Quirosville’, Sydney Gazette, 27 January 1831, p. 3; Samuel Bennett, The History of Australian Discovery and Colonisation, Sydney: Hanson & Bennett, 1865, p. 116; Sydney Morning Herald, 26 January 1886, p. 6.

[34] John Bingle, ‘Birthday Thoughts in New South Wales, Australia’, 1878, original in Mitchell Library, quoted in John Earnshaw, ‘Source Notes Regarding the First Landing and Foundation Tree, West Side of Sydney Cove’, c. 18 October 1963, submission to the Herron Committee, Sydney City Council Archives, Item No.4454 of 1963.

[35] Sydney Morning Herald, 27 May 1882, p. 7. Brennan wrote to the Herald under the pseudonym ‘Cattai Creek’, but we know it was Brennan because exactly the same account was published following his death with his name attached - The Newsletter, 3 November 1906, p. 2.

[36] Sydney Morning Herald, 8 October 1897, p. 3. See also Sydney Morning Herald, 24 October 1900, p. 5; 5 November 1900, p. 7; 9 May 1902, p. 3 & 11 February 1904, p. 6.

[37] Truth, 28 July 1912, p.12.

[38] Evening News, 17 November 1875, p.2.

[39] Joseph Fowles, Sydney in 1848, Sydney: J. Fowles, 1848, p. 8.

[40] W & F Ford’s Guide to Sydney, 1851. There are no copies of this publication in any Australian libraries, but it is quoted in A.G. Foster, Early Sydney, Sydney: Tyrrells Ltd, 1920, p. 97. Foster attributed it to a letter from ‘A Member of the Historical Society’ in the Evening News of 1918, but no copy of this letter has been found.

[41] Agnes Farrell to the Lord Mayor, 24 April 1907 & Farmer & Co to Mr W.G. Layton, 13 May 1907, Item No.1452 of 1907, Sydney City Council Archives (hereafter SCC Archives).

[42] Sydney Morning Herald, 28 January 1907, pp. 7 & 8.

[43] Sydney Morning Herald, 23 January 1926, p. 11 & 25 February 1933, p. 9.

[44] Lachlan and Elizabeth Macquarie Archive, at https://www.mq.edu.au/macquarie-archive.

[45] Alfred Lee, ‘The Landing of Governor Phillip in Port Jackson’, The Australian Historical Society Journal and Proceedings for 1901, (1906), Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 2-3; Alfred Lee, The Official Landing Place of Governor Phillip at Sydney Cove, 26th January 1788, Sydney: Alfred Lee, 1900. Lee also sent several letters to newspapers on this subject in later years.

[46] John Easty, Memorandum of the Transactions of a Voyage from England to Botany Bay, 1787-1793, Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1965, p. 96.

[47] For example, the editors of the Historical Records of New South Wales stated in a foot note: ‘The British flag was unfurled at the head of Sydney Cove. . .’ – Alexander Britton (ed.), Historical Records of New South Wales, Sydney: Government Printing Office, 1892 – Vol. 1, No. 2, p. 122.

[48] Philip Gidley King, `Remarks & Journal kept on the Expedition to form a Colony in His Majestys Territory of New South Wales. . . , 24 October 1786 - 12 January 1789’ (Private Journal, Vol.1), SLNSW Safe 1/16, p. 86; David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, London: Cadell & Davies, 1798, pp. 5 & 6; Watkin Tench, A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay. . ., London: J. Debrett, 1789, pp. 60-61; John Campbell to his parents, SLNSW, MLMSS 7525; Log of the Fishburn, TNA ADM51/4375, 29 January 1788.

[49] See Sydney Gazette, 5 June 1803, p. 1, where the foundations of a stone bridge are described as being built across the head of the cove.

[50] William Bradley, ‘A Voyage to New South Wales’, December 1786 to May 1792, SLNSW Safe 1/14.

[51] Australasian Pioneer’s Club, ‘Determination of the Site on which the First Landing on the Shore of Sydney Cove was made and the English Colours Displayed on January 26, 1788’, M.H. Ellis Papers, SLNSW, ML MSS 1712, Box K21889.

[52] William Bradley, ‘Journal of HMS Sirius, 1787-1792’, Australian National Maritime Museum, 00055232.

[53] William Bradley, ‘Sydney Cove, Port Jackson’, c.1802, in William Bradley, ‘A Voyage to New South Wales’, op. cit., opposite p. 84.

[54] J. Bartrum, A Charge of Mutiny, London: Sherwood, Neely & Jones, 1811.

[55] Sydney Morning Herald, 8 April 1911, p. 12; Sydney Morning Herald, 29 January 1921, p. 13; Evening News, 31 July 1922, p. 7; Sun, 10 March 1923, p. 4; Sun, 11 March 1923, p. 13; Daily Telegraph, 22 January 1927, p. 5; Freeman’s Journal, 20 December 1928, p. 18; Sydney Morning Herald, 16 August 1930, p. 11.

[56] Hobart Mercury, 30 May 1939, p. 6.

[57] Sydney Morning Herald, 31 December 1926, p. 10.

[58] Sydney Morning Herald, 11 December 1926, p.11.

[59] Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘Journal of Arthur Bowes Smyth, 22 March 1787 to 8 August 1789’, NLA MS4568, 24 & 25 January 1788, which reports Major Ross issuing orders for Lieutenants George Johnston and William Collins to join the Supply the next day.

[60] Douglas Hope Johnston, ‘The Only Authentic Relic of the First Landing in Sydney’, pp. 6-7 & 12, in Douglas Hope Johnston Archive, SLNSW, ML MSS6485. He never made these claims in public, and in one newspaper article, he stated that no one was allowed to go ashore on the evening of the 25th – Bath Chronicle, 5 June 1937, p. 8.

[61] M.H. Ellis Papers, SLNSW, ML MSS 1712, Box K21889.

[62] Douglas Hope Johnston papers, ML MSS 6485, part 4, folder 1, quoted in Alan Roberts, Marine Officer, Convict Wife, Sydney: Annandale Urban Research Association, 2008, p.19.

[63] Sydney Morning Herald, 26 January 1923, p. 6. David Collins’ Account, the anonymous Voyage of Governor Phillip, and journals of the surgeons, John White and George Worgan, say that the ceremony was held in the evening. Phillip’s dispatches do not refer to the ceremony, so the source of the passage in the Voyage is unknown – possibly Collins as the Governor’s secretary. The Sirius, which was carrying Collins and Worgan, arrived off the cove around 5pm, but Collins was clear that the only officers present at the ceremony were those who had come round with Phillip in the Supply. Hope Johnston’s 7pm timing is clearly wrong.

[64] Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 1 October 1842, p. 2.

[65] Algernon Talmage, ‘The Founding of Australia 1788’, 1937, Tate Britain NO4877. The State Library of NSW holds a preparatory oil sketch at ML 1222.

[66] Earnshaw to Chisholm, 21 April 1960 in Alec H. Chisholm archive at SLNSW ML MSS 3540, Box H4981, First Fleet file.

[67] Item No.399 of 1963, SCC Archives.

[68] Al. P. Lazarev, Zapiski o plavanii voennogo shliupa 'Blagonamerennogo . . (Notes on the Voyage of the Sloop-of-War ‘Blagonamerennyi’. . .), Moscow: Geografgiz, 1950, translated and published in Glynn Barratt, The Russians and Australia, Vol.1, University of British Columbia Press, 1988, p. 150.

[69] Port Jackson Painter, ‘New South Wales, Port Jackson from the Entrance up to Sydney Cove’, October 1788, Natural History Museum, Watling Drawing, No.LS2.

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.