George Worgan’s Letter

The only known account of the settlement by George Worgan, the surgeon of HMS Sirius, is a letter sent to his brother Richard in July 1788. But Worgan's letter bears a close resemblance to the letters and journals of other gentlemen on the First Fleet.

Gary L. Sturgess

6/8/20238 min read

It is a combination of letter and journal, but it is more complicated than that, with similarities in structure and language to the writings of six other officers and gentlemen. Worgan was aware of his limitations as a chronicler of history, spending much of his time on board the Sirius, which was anchored just outside Sydney Cove. It seems that he overcame these difficulties, in part, by sharing stories with other journal-keepers.

This newsletter employs textual analysis to explore this exchange of anecdotes, in the hope of better understanding how some of these letters and journals came into existence.

George Bouchier Worgan

George Worgan was the surgeon on HMS Sirius from November 1786, when he joined the ship for her voyage to New South Wales, until March 1790, when she was wrecked off Norfolk Island. He would certainly have obtained his appointment through patronage, but we do not know who brought him to the attention of Arthur Phillip, the captain of the Sirius and commodore of the fleet. Along with the officers and crew of the Sirius, he returned to England on the Waaksamheyd in early 1792.

His father was a celebrated organist who held appointments at the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens and a number of churches throughout the City of London, and who socialised with Handel. George became a naval surgeon at his father’s insistence, but he was musician enough to take his piano with him on the voyage to New South Wales.

He was the most senior of the medical practitioners involved in the expedition, but Worgan was assigned to the Sirius and had little to occupy his time during the three years that he was in the colony. He managed scurvy and syphilis amongst the crew, conducted autopsies, attended to a man who had been viciously assaulted by fellow crew members, provided evidence at their trial and then advised as to their fitness for flogging. He sailed to the Cape of Good Hope in the Sirius in October 1788, and dealt with a dreadful outbreak of scurvy which killed several of the men after they rounded Cape Horn.

There was a garden, probably on Garden Island (which had been assigned to the crew of the Sirius to raise fresh fruit and vegetables). His peas and beans grew well, and the potatoes and turnips, but the soil was sandy and in general his vegetables did not prosper.

We know little about his social activities, but there would have been dinners with the other gentlemen: with the only piano in the colony, small and with folding legs, Worgan was no doubt a popular dining companion.

He attended the dinner organised by Phillip on the 7th of February 1788, the day he was sworn in as Governor, and celebrated the King’s birthday at the Governor’s canvas house on the 4th of June.

He went for walks in the woods that surrounded the settlement – out to the Brickfields (near what is now Central Railway Station), across to the Governor’s farm (alongside what is now Farm Cove), over to the look-out that had been established at South Head. He joined the other gentlemen on hunting parties, sometimes staying out overnight. He participated in a number of exploratory expeditions: for a brief time, part of the Nepean River was named after him. And in December 1790, Worgan was assigned to a military expedition sent out to punish Aborigines who had killed the Governor’s game-killer: fortuitously, no one was found. But for much of his time in the colony, Worgan must have been bored.

On his return to England in April 1792, he joined a hospital ship moored at Plymouth. Officially, Worgan was assistant to the surgeon, Thomas Mein, with whom he had worked in North America at the end of the War of Independence. But the main reason for going to Plymouth was to assist Mein in managing his naval contracting business. It did not turn out well, with both men later coming under scrutiny from a commission of inquiry.

George Worgan finally quit the navy around 1799, worked unsuccessfully as a gentleman farmer for some years, before falling on hard times. Through family connections, he was appointed to conduct an agricultural survey of Cornwall, but his final years were spent as a humble schoolteacher at Liskeard (in Cornwall), where he died in 1838, at 80 years of age.

Worgan’s Journal and Letters

The only known manuscript in Worgan’s own hand is a letter written to his brother Richard in June and July 1788. He wrote 30 other letters to friends and family around that time, and more in April and November of that year as other First Fleet merchantmen were preparing to sail for home. Others would have been written as the ships of the Second Fleet were weighing anchor for China in late 1790, but if any of these have survived, they remain buried in family archives.

He also kept a rough journal, covering the outward voyage and his time in the settlement – it was not written for publication, and it is unknown whether he ever created a fair copy. In any case, it has not survived or it remains lost, and the only passages we have are the extracts which he transcribed into his letter to Richard.

George knew that he was not in the best position to write an account of the early colony. As he explained to his brother:

My Situation on Board the Ship will not admit of my collecting all the Incidents Occurrences, Remarks &c and if I had Matter, I have neither Genius nor Abilities to Relate it in a tolerable Manner.

Some of Worgan’s anecdotes are clearly first-hand – his account of the commissioning ceremony held on the 7th of February, the celebration of the King’s birthday, several trips up and down the harbour – but in a number of cases, we know that he is relying on someone else, because he was not present when the events in question occurred.

Moreover, a number of Worgan’s stories have a textual similarity to passages in the letters and journals of other officers and gentlemen. This does not happen by accident, which means that Worgan was borrowing text from the letters and journals of these other gentlemen, they were copying from him, they were all drawing on texts written by unknown third parties, or it was some combination of the above.

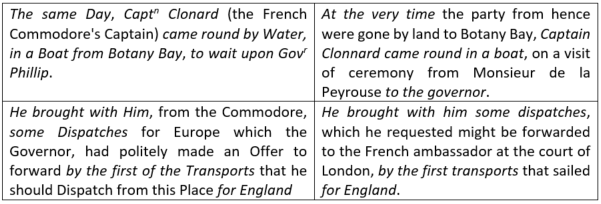

Text in Common with John White

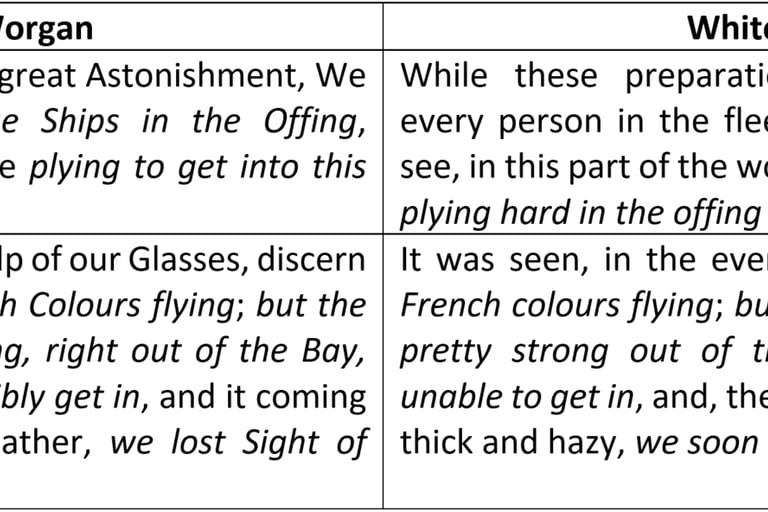

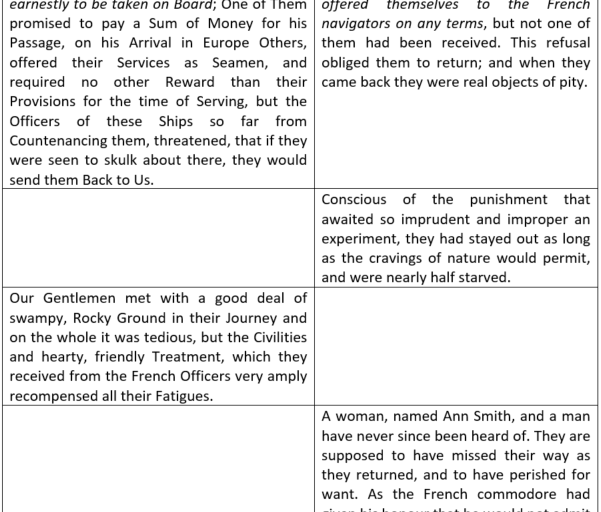

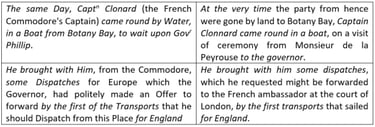

Half a dozen such examples can be found in the journal published by the surgeon-general, John White, with whom Worgan would have socialised when he was on shore. These are passages where the structure and language are similar to text in Worgan’s letter. Table 1, for example, compares Worgan’s description of the events of 24 January 1788 – as the fleet was trying to make its way out of Botany Bay to sail for Port Jackson, and as the ships of the La Perouse expedition suddenly appeared in the offing – with the account provided by White.

Table 1: Sailing from Botany Bay

It is not possible that these two accounts were created separately – either White and Worgan was drawing on some unknown third account, or one of them was borrowing from the other. It is unclear why one (or both) needed to borrow text, since they were both present that day, but there can be no question that copying was involved.

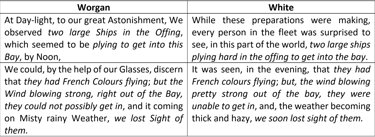

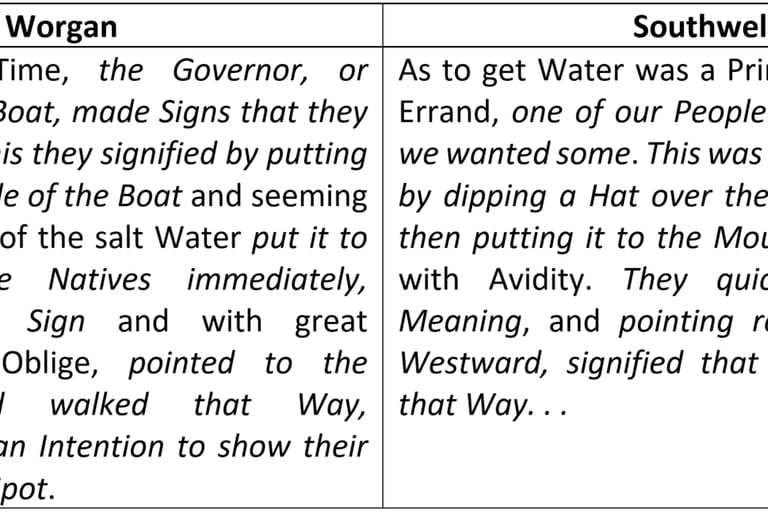

A second example is Worgan’s account of a visit by some of the British gentlemen to Botany Bay on the 8th and 9th of February 1788, to meet with officers of the La Perouse expedition. There is nothing to suggest that Worgan or White were members of this party, in which case, they were both borrowing from someone who was. This conclusion is reinforced by the fact that each of them has a great deal of material that is not in the other:

Table 2: A Visit to Botany Bay

Text in common with the Officers of the Sirius

It does not come as a surprise that Worgan might have been exchanging material with the officers and young gentlemen of the Sirius, with whom he spent so much time. What is surprising is that he was sharing with so many.

Daniel Southwell

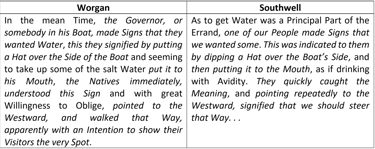

Neither George Worgan nor Daniel Southwell was in Botany Bay on the 18th of January: they arrived two days later in the Sirius, but they both used similar language to describe one of the events which occurred that day.

Table 3: Finding Water

Henry Waterhouse

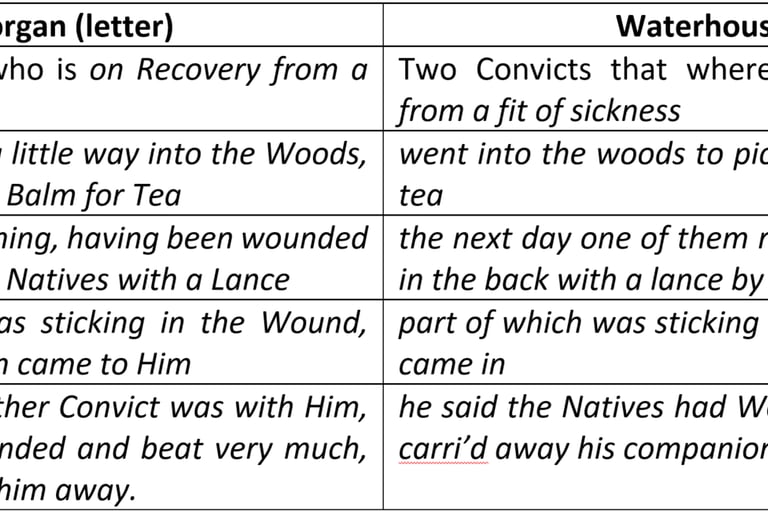

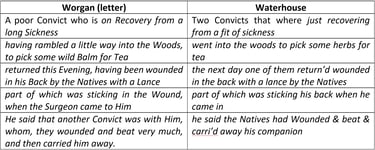

A number of sources report an attack by Aboriginals on a convict named William Ayres, when he wandered out into the woods in May 1788 to forage for a herb used in making tea. In this case, Worgan’s passage is virtually identical to that of midshipman Henry Waterhouse. It is possible that one of them was on shore that day, but it seems more likely that one or both of them were borrowing from a third party.

Table 4: The Spearing of William Ayres

John White was the attending surgeon, but in this case, his account and Worgan’s are quite different.

William Bradley and Newton Fowell

Worgan is one of the three sources to tell a story about an Aboriginal who scalded his hand trying to take a fish out of a cooking pot. The other two are William Bradley, the 1st Lieutenant of the Sirius, and Newton Fowell, one of the midshipmen. In this case, the structure and language are not especially close, and all three seem to be drawing on a story that someone had recounted, rather than a single written source.

Text in common with Watkin Tench

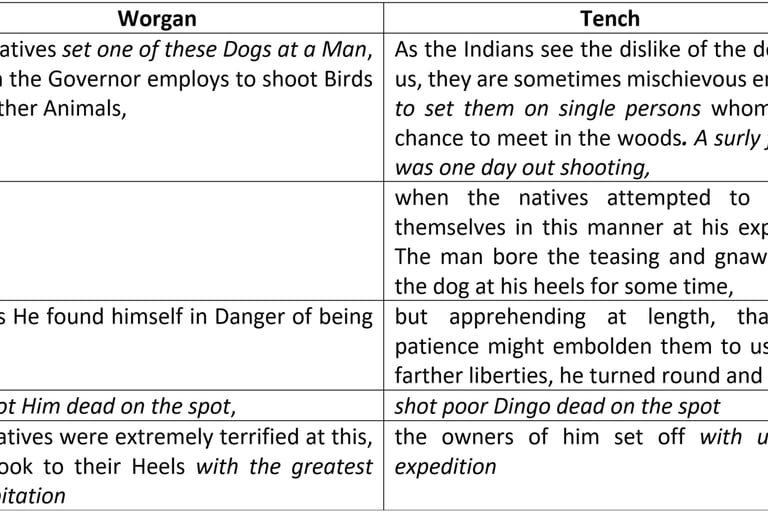

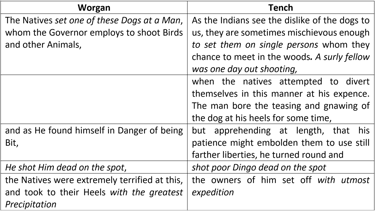

Worgan and Tench are the only sources for another story, about a dingo shot by one of the officers’ game-killers when it was sooled on him in the woods. There are also similarities in language, reinforcing the conclusion that the two accounts are in some way related.

Neither of them provides date or context, but both were completed before mid-July 1788, when the merchantmen sailed for home carrying Worgan’s letter and the manuscript for Tench’s book.

Table 5: A Dead Dingo

Analysis

The relationship between these texts is complicated, and it is not clear who was borrowing from whom. Worgan is the common denominator – there are not the same relationships between these other sources as there are with him – but does this mean that he was more active in borrowing the others’ journals, or, knowing that he was collecting stories, were they borrowing from him?

While some of them have details that are not in Worgan’s letter, it is possible that they were drawing on much longer accounts in his original journal. On the other hand, Worgan might have been drawing on a more comprehensive version (say) in the original of John White’s journal.

For the present, these questions cannot be answered. What is clear is that closer attention must be paid to textual analysis in the study of First Fleet sources.

George Worgan’s piano (Edith Cowan University)

Richard Worgan at the piano with John Constable, among others, 1806 (British Museum).

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.