Forgotten First Fleeters 1: Charles Prater

Charles Prater sailed to New South Wales with the First Fleet and served on the staff of the Governor’s official secretary, David Collins. He was the teenage son of a wealthy London draper, and has been largely overlooked, in part because he left no children in the colony (and so much First Fleet research is undertaken by family historians); and because professional historians have not seriously studied the workings of the early penal settlement.

Gary L. Sturgess

4/30/20256 min read

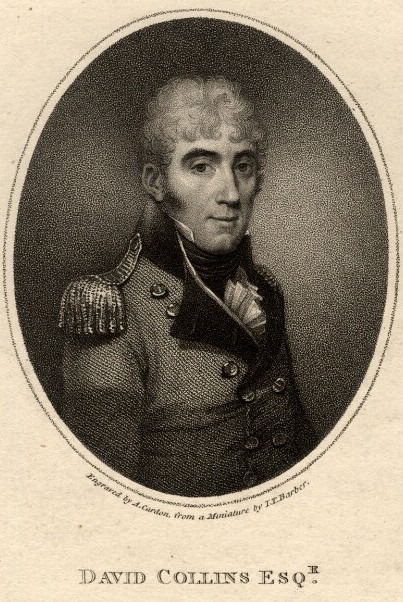

Given the immense responsibility that rested on David Collins in the early years of the colony – he was the Governors’ official secretary as well as the Judge Advocate and Chief Magistrate – the organization of his office should have been the subject of great interest to the historians of early European Australia.

Yet almost no attention has been paid to this subject or to Charles Prater, the ‘servant’ who sailed with Collins on HMS Sirius in May 1787 and returned on HMS Gorgon in December 1791. Mollie Gillen gave him two brief paragraphs in her ‘Biographical Dictionary of the First Fleet’, and to my knowledge, no one else has done any work on him.

There is one reference to Collins’ servant in the records of the early colony, which gives us some idea of how Prater was employed – when, on 28 July 1789, a group of convicts who had served their time, handed him a petition for the Governor, to be passed on by Collins as the Governor’s official secretary.

But Prater must have played an important part in organising Collins’ papers, managing the official archive and keeping the daily account of proceedings in the settlement, on which Phillip and Collins later relied when writing up their journals.

So, who was this man?

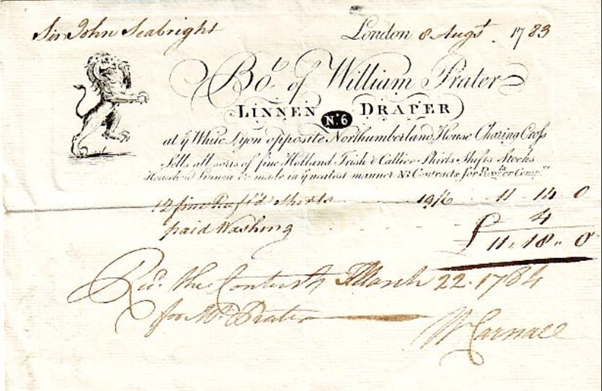

William Prater & Son

Charles was the son of William Prater, a wealthy draper and army clothier whose store and counting house was located in Charing Cross, in London’s West End, close to where Trafalgar Square now stands. He was born in August 1771 and baptized several weeks later at St Martin in the Fields, just around the corner from Charing Cross. Charles was fifteen and a half years old when he joined Collins on the Sirius and given this background, we can be certain that he was both literate and numerate.

William Prater had a particularly close relationship with the Royal Marines, and when the First Fleet was being commissioned in 1786, he was approached to supply shirts and necessaries – soap, pipeclay, needles, razors etc., as well as drumheads, snares and drumsticks, and fifes and cases for the drummers.

The firm would send out bulk supplies for regiments across Britain and the Empire, as far afield as India and Canada. Officers would visit the Charing Cross store to have their uniforms made to specification, and Prater acted as an agent for some of his customers. It is not difficult to imagine the circumstances by which young Charles came to be recruited as David Collin’s assistant in the establishment of this new colony.

Given William Prater’s prominence in military circles, it is unsurprising that the firm turns up numerous times in the records relating to the colony. Among other examples.

· Lieutenant Edward Riou, commander of the ill-fated Guardian, who sailed for NSW in September 1789, purchased a number of articles from Mr Prater before sailing.

· Major James George Semple, a notorious mountebank, defrauded the Praters of half a dozen shirts and several guineas in 1794. William’s evidence contributed to Semple’s conviction and a sentence of transportation – he never made it to Australia because the Lady Shore, the ship on which he was sailing, was seized and taken into South America by mutinous guards.

· In 1803, when David Collins returned to Australia as the Lieutenant Governor of a proposed new settlement at Port Phillip, Prater & Son supplied Collins and the marines with a number of ‘necessaries’.

· From 1819, Charles Prater and Son acted as an agent for Barron Field, a civil court judge who had arrived in NSW two years earlier.

· And they shipped supplies to Major Frederick Goulburn when he was appointed as NSW Colonial Secretary in 1820.

Charles Prater at Home

On his return to London in June 1792, Charles went to work with his father in the Charing Cross drapery, becoming a partner several years later, and then taking over the business around 1819, when his father retired.

He had lived through the worst years of the penal settlement, sharing the challenges involved in carving out a livable space in a hostile environment and establishing a self-sustaining community, and he had been directly involved in managing this society day-to-day, relying heavily on convicted criminals. He had spent months on short rations when the Guardian failed to arrive in 1789, and again from June 1790 when the Sirius was wrecked on Norfolk Island. He had witnessed the suffering and death which accompanied the Second Fleet on its arrival in June 1790, and if he was not a personal witness, then he was fully aware of the mass graves at Toongabbey following the arrival of the Third Fleet in the second half of 1791. It would be surprising if, on going home, Charles did not take an interest in the young men and women who were being sent out to the colony.

His father’s business was often targeted by criminals, cloth and clothing being valuable articles at the time and easy to pawn or sell. Charles and his father appeared as prosecutors in the courts on numerous occasions.

In August 1792, two months after Charles’ return, his father dismissed an employee, John Gaitskell, whom he suspected was stealing property. Gaitskell came back the following day and tried to settle their differences with a payment of £160. This had quite the opposite effect: William told him to leave the premises and threatened to send him to Botany Bay. Outraged, he then arranged for Gaitskell’s apartments to be searched: they found three large boxes with property belonging to Prater and others, valued at £300-400.

The systematic theft of articles on this scale was a capital offence, but Prater only charged him with simple larceny of half a dozen handkerchiefs and neckcloths valued at £1.17.0. Gaitskell was found guilty and sentenced to seven years transportation, but a campaign was immediately launched by his family and friends to have him be pardoned on condition that he take himself into exile. Prater supported them with a strong recommendation that Gaitskell be pardoned (and thus not sent to NSW). A petition was subsequently submitted, with a letter of support signed by Prater himself, and he was pardoned on condition that he take himself out of the kingdom. It is unclear what happened in the interim, but in October 1793, Gaitskell was given a full pardon.

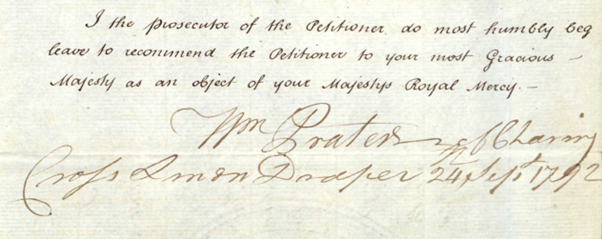

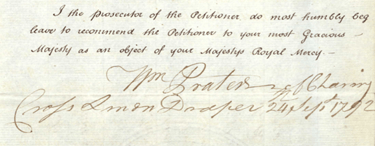

Bill of William Prater, 8 August 1783

William Prater’s note in Gaitskell’s petition, recommending mercy. (Petition of John Gaitskell, 28 September 1792, UK National Archives, HO47/015)

We have no direct evidence , but one can imagine that Charles, so recently returned from the penal colony, might well have spoken to his father about the consequences of sending Gaitskell to NSW.

David Collins

David Collins returned to England in 1797, remaining in London for some time while he negotiated the next steps in his career. In August and September of that year, he resided at 19 Charing Cross, and there can be no question that he attended Charles’ wedding to Theodosia Elizabeth Caldwell on the 2nd of September, held just around the corner at St Martin in the Fields.

As noted above, when Collins returned to Australia in 1803, he turned to Prater & Son once again for supplies.

Family Life

Charles and Theodosia Elizabeth (as she was known) had five children who lived to adulthood, with the eldest son, also named Charles, following his father into the Charing Cross drapery. Charles (senior) was involved in a variety of good causes, and in 1831, at the age of 60, he was appointed as a Deputy Lieutenant of Middlesex, a position of high social standing. Around the same time, he and Theodosia Elizabeth moved to a substantial home in Portland Place, where they lived for the next three decades with two of their daughters, a granddaughter and 11 servants.

Charles passed away in 1861 at the age of 89. His death was reported in a number of papers, where he was referred to as an army clothier or army tailor. The Bombay Gazette described him as ‘a man personally well known to many in India’. His estate was valued at around £200,000, a considerable fortune at the time.

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.