Clothing

11/3/20244 min read

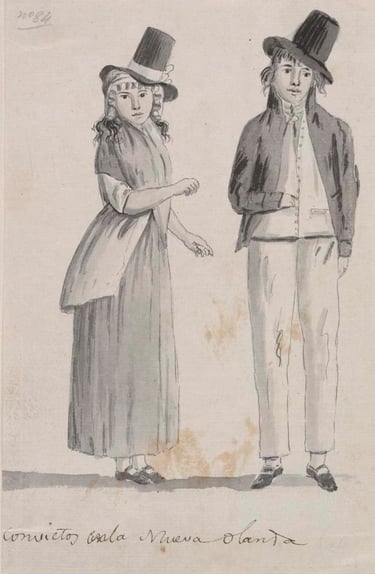

Juan Ravenet, ‘Convictos en la Nueva Olanda’ [Convicts in New Holland], in Felipe Bauza, ‘Drawings made on the Spanish Scientific Expedition to Australia and the Pacific. . .’, 1793, State Library of NSW, SAFE DGD 2

Slops

In the period covered by this project (1787-1800), convicts did not wear uniforms, with or without the broad arrow, the logo long used by the Crown to mark its property.

Leaving aside the hats, the drawing of two Port Jackson convicts made in 1793 by Juan Ravenet, an artist on a Spanish scientific expedition, gives the best idea of what the convicts in this period were wearing.

With the First Fleet, it was intended that the convicts would wear the clothes in which they first came on board, but this proved to be unworkable when many of the women arrived inadequately dressed for the winter weather. The commodore of the fleet (and Governor-elect), Arthur Phillip, ordered the women to be issued with a complete range of clothing from the articles that had been sent on board for use in the colony. There appears to have been a great deal more variety in these articles than the clothing supplied from the Second Fleet onwards. The jackets were in grey, white, check and woollen, and the petticoats (a skirt rather than an undergarment) were in canvas, linsey, woolsey and serge.

From the Lady Juliana (1789), a clothing allowance for the voyage itself was specified in the contract – each woman was to be supplied with a striped cotton jacket, one striped cotton petticoat and two flannel ones, two shifts, two pairs of stockings and two pairs of shoes, a hat, a cap and two handkerchiefs. From 1790 to 1792, the women were also issued stays (supportive undergarments).

The matching jacket and petticoat were working class fashion at the time (later adopted by the genteel classes). Striped fabrics were also fashionable, and it is interesting that cotton was sufficiently commonplace for the jackets and petticoats to be made from it. The ‘handkerchief’ was worn around the neck and the caps were almost certainly white ‘mob’ caps. Women did not wear knickers at the time, and none were supplied by government. (I had an exchange with my late friend and colleague, Alan Frost, over this, and on checking, he agreed that he had made an unwarranted assumption in The First Fleet: The Real Story - see article Colony No Ship of Fools: Review of Alan Frost, 'The First Fleet: The Real Story') There is evidence of the women making alterations to their slops as soon as they were issued.

The men were issued with a jacket and a waistcoat, two pairs of trousers and two check shirts, two pairs of drawers, two pairs of stockings and two pairs of shoes, a hat and a cap. In 1794, the Transport Board replaced two pair of trousers with one pair made out of ‘Russia duck’, a hemp linen material with a glazed finish which helped shed water. Men did wear drawers at this time, although they were probably optional for the lower classes, which may explain their disappearance from the lists after 1792.

Léon Collin, Photograph of French convicts washing on a transport bound for French Guiana, 1906-1910, Musée Nicéphore Niépce de Châlon-sur-Saône

Washing & Drying

From the Second Fleet (1790), the agents for transports were instructed to ensure that the convicts’ clothes were routinely washed and changed. No instructions were given as to how often this was to be done, but there was at least one washing day a week and often two. As noted elsewhere, Saturday was generally one of these days, so they would have clean clothes for Sunday.

Their clothes were washed in the bathtubs, using cold seawater and marine soap, although rainwater caught in the awnings was used when it was available. White linen went grey over time and there is evidence that pipe clay, used for whitening leather, was sometimes employed.

Washermen and women are mentioned on some of the ships – two men or women drawn from each of the messes – but where there were a significant number of women on board, they were sometimes responsible for the men’s laundry as well. There was also a trade in laundry services – convict women washing for the officers and gentlemen, and even the crew, with payment in tobacco or tea, and there are examples of men doing the laundry for other messes, in return for beef or pudding.

Some of the them would hide their dirty linen and put it on again as soon as they had been mustered in their clean outfits. Some imitated the sailors in towing their clothes behind the ship, with a rope lowered through one of the portholes. Inevitably, some of the clothes were lost in this way, and the ships’ officers and convict superintendents issued prohibitions against it.

After washing, the clothes would be hung on the rigging or lines strung up across the deck. These articles were usually numbered so they could be returned to their owners, and they would be inspected before being taken down, to ensure that damp clothes were not brought into the prison.

The earliest mention of the women having access to flat irons is 1821, but they were probably in use much earlier. There were irons on the First Fleet, although it is unknown whether the convicts had access to them.

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.