Cable v Sinclair - The Aftermath

Lawyers and historians are familiar with Cable v Sinclair, the first (reported) civil court case in Australian history, where convicts Henry and Susannah Kable sued the captain of one of the First Fleet ships over the loss of some of their property on the outward voyage. They are not aware of the precedent which this set, and the cases following the arrival of the Second Fleet, where other convicts brought actions over missing property.

Gary L. Sturgess

6/27/20245 min read

Cable v Sinclair (Court of Civil Jurisdiction, July 1788) is a landmark case, in part because Henry Kable and Susannah Holmes had originally been sentenced to death, and in English law, they had lost their right to bring a civil action in the courts to enforce their rights. But in the course of the voyage, Governor Phillip had come to the realise that the colony could not function if three quarters of the residents lacked the ability to protect themselves and their property. In effect, he declined to adopt those aspects of English law relating to felony attaint.[1]

The case is also significant because the Kables won, and Captain Sinclair was directed to give them a ‘note of hand’ for £15 (which Henry sent home to his mother – among other reasons, because a bill of exchange would have been difficult to negotiate in the newly-established colony).

Cable v Sinclair is also noteworthy because, if naval vessels had been used to ship out the convicts and their belongings, the commander of the ship could have pleaded Crown immunity, and he would not have been held vicariously responsible for the loss of their property. However, since Duncan Sinclair was a private contractor employed by the Navy Board, Crown immunity did not apply, and they had a defendant from whom their could recover their losses.

But the case also matters because it served as a precedent: in 1812, the former NSW Commissary, John Palmer, who had arrived with the First Fleet, told a British parliamentary inquiry that if the convicts made a complaint upon arrival:

"...it was generally put down and delivered to the Governor in writing... Sometimes their money has been intrusted to the mates, and not returned, and the business has been inquired into before the magistrates, and they have been redressed."[2]

It is difficult to know how common these actions were in the early years, since very few transcripts of civil court proceedings survive from before 1795, and the records of the bench of magistrates are missing between January 1792 and June 1798. However, other documents in the UK National Archives make it clear that the precedent of Cable v Sinclair was followed as early as the winter of 1790, with the arrival of the Second Fleet.

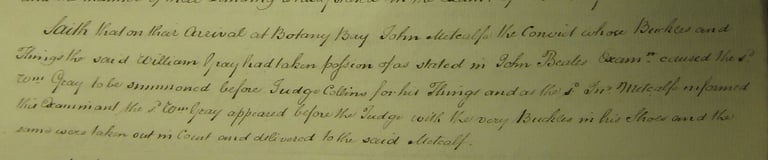

The evidence relating to Metcalfe v Gray is to be found in a deposition taken from George Churchill, a crew member of the Neptune, in preparation for a court case in England. Churchill stated that shortly after their arrival in the colony, he was approached by a convict named John Metcalfe, who claimed that the ship’s surgeon had refused to return some of his property. It was conventional for the convicts to hand their valuables to the ships’ officers for safekeeping, and Metcalfe claimed he had given the surgeon a pair of shoe buckles, commonly used by travellers as an alternative to cash.

The son of a master tailor from London, Metcalfe came from a respectable family, and in a petition for clemency on his behalf, his father had marshalled the support of church wardens and overseers, as well as three dozen local tradesmen (the petition failed because young Metcalfe had been an active member of a local gang). Shortly before the fleet sailed from Portsmouth, his father had brought a package of personal items on board, including this pair of shoe buckles, which the surgeon, William Gray, now refused to return.

Churchill brought the matter before the Judge Advocate, David Collins, and Collins ordered Gray and Metcalfe to appear before the court. Gray arrived wearing the buckles and after hearing the convict’s evidence, Collins directed that he immediately return them.[3]

The Second Fleet papers in the UK National Archives suggest there might have been another such action. In the final stages of the voyage, the master of the Neptune, Donald Trail, accused one of the female convicts of stealing a piece of cloth. It seems that Trail had used some of the women to make tablecloths (sixty of them) out of patterned material supplied by himself, for sale in the colony. Following a tipoff, he ordered this woman’s trunk to be opened, where (he said) a remnant of this material was found.

The woman in question, Ann Wheeler, was a literate, middle class convict, from a family of London criminals who had a reputation for vigorously defending themselves (see Newsletter 13 on the McCouls). We don’t know precisely what happened, but Trail threw her trunk (described as a very good one) overboard, and seized the contents, which included ‘many valuable articles for Housekeeping such as Sheets, Table cloths &c’. He also had her confined on the gun deck for the final two or three weeks of the voyage, presumably because she had responded vigorously to his actions.

He later claimed that he had taken her belongings because he intended to prosecute her on arrival, but instead of doing so, Trail returned all of her property, along with the disputed piece of cloth. Donald Trail was a hard man, and he would not have done so out of the goodness of his heart. Given what we know of Wheeler’s temperament, it seems likely that she either took him to court or threatened to do so, and that he backed down.[4]

It should be noted that the precedent of Cable v Sinclair was not confined to actions against ships’ captains. From 1796, and probably earlier, convicts were suing and being sued in the court of civil jurisdiction over breach of contract and unpaid debts, to the extent that Governor Hunter had to issue a directive to prevent convicts, who should have been working for government, being sent to the debtors’ prison.

___________

[1] There are a significant number of articles on Kable v Sinclar, but see, for example – David Neal, The Rule of law in a Penal Colony, Cambridge University Press, 1991, pp. 1-8; Bruce Kercher, Debt, Seduction & Other Disasters: The Birth of Civil Law in Convict New South Wales, Annandale: The Federation Press, 1996, pp. 52-53; Bruce Kercher, ‘Resistance to Law under Autocracy’, The Modern Law Review, (1997) Vol. 60, No. 6., pp. 779-797 at pp. 784 & 797; Ian Temby QC, ‘Australia’s First Litigants’, Bar News, Summer 2009-2010, pp. 85-87.

[2] ‘Report from the Select Committee on Transportation’, 10 July 1812, House of Commons Papers: Reports of Committees, No. 341, p. 61.

[3] George Churchill Examination, UK National Archives, TS11/381, p. 15.

[4] Charles King Examination, ibid., p. 49; Statement of Donald Trail, ‘Accounts and Papers Relating to Convicts on Board the Hulks, and Those Transported to New South Wales’, Ordered to be Printed 10th and 26th March 1792, House of Commons Sessional Papers of the Eighteenth Century, (83) 1791-92, p. 76.

Extract from the examination of George Churchill

Judge Advocate's house, where the court cases were heard.

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.