A New King Journal

A previously unknown version of Philip Gidley King’s First Fleet journal has come to light in the Royal Collection at Windsor. It differs from the two narrative versions, the so-called Private Journal and Fair Copy, held by the Mitchell Library in Sydney, and offers new insights into the voyage across the Southern Ocean, the early weeks in the settlement, King’s time on Norfolk Island and his return to England in 1790.

Gary L. Sturgess

3/5/202313 min read

It has been argued that the Private Journal is the original, with the Fair Copy based on it, but the RCT version, written in the form of a ship’s journal, makes it clear that the original was King’s version of a ship’s log, written day by day throughout the voyage and during his time in the colony. All three journals are fair copies based on the original, but they draw on different details as well as other contemporary sources.

RCT enables us to better understand how King wrote his journal and how the various copies were constructed. Comparison of all three versions reveals fascinating and sometimes unexplainable discrepancies, and serves as a reminder that historians must access all of the available sources if they wish to understand what happened on the First Fleet and in the early days of the settlement.

Among other things, RCT confirms that the flag-raising ceremony on 26 January 1788 occurred in the afternoon and not in the morning, as some had concluded based on the Private Journal.

The King Journals

Philip Gidley King was second lieutenant on the Sirius on her voyage to New South Wales with the First Fleet. He served as Phillip’s aide-de-camp throughout the voyage, and accompanied the Commodore when he moved across to the Supply shortly after leaving the Cape, with the intention of arriving at Botany Bay ahead of the fleet. On their arrival, King was assigned the responsibility of exploring Botany Bay. He accompanied Phillip on the Supply when she sailed to Sydney Cove on the 25th of January to make the first landing. He was sent across to Botany Bay on the 1st of February for an official meeting with La Perouse. And several days later, he was appointed by Phillip to establish a small settlement on Norfolk Island. King was sent home with dispatches in 1790, but returned to serve as Lieutenant Governor of Norfolk Island and later as the third Governor of NSW.

A number of King’s journals, letter-books and papers have survived, including two journals covering his first voyage to NSW and the first two years he spent on Norfolk Island. One of these, known today as the Fair Copy, was acquired by the Sydney Public Library in 1897 and is now held by the Mitchell Library. It was purchased from Francis Edwards, an antiquarian bookseller in Marylebone, but beyond that, its provenance is unknown. Part of this version was included in John Hunter’s Historical Journal, published in 1793, and some historians have argued that it was handed to the Secretary of the Admiralty on King’s return to London in December 1790. The original can be viewed on the State Library of NSW website.[1]

The other version, known to historians as the Private Journal, consists of two volumes, and was acquired by the Mitchell Library in 1933 from King’s descendants. The text was first published by F.M. Bladen in 1893 in Volume 2 of the Historical Records of New South Wales, having been given access by the family, and it was republished by the Australian Documents Library in 1980 with Paul G. Fidlon and R.J. Ryan as editors. The original can be seen on the State Library of NSW website, and the University of Sydney has published a transcript.[2]

Both documents are in King’s handwriting, although Fidlon and Ryan noted that some passages of the Private Journal were written by someone else, presumably a clerk. They concluded that the Private Journal was a ‘rough copy’, from which the Fair Copy was transcribed, although a close reading makes it clear that the relationship is more complicated than this: the Fair Copy contains details, some quite specific, which are not mentioned in the Private Journal, which suggested that there was at least one other source.

A Third Version

The current understanding of the Private Journal and its relationship with the Fair Copy must now be revisited following the emergence of this third and previously unknown version, held by the Royal Collections Trust.[3] Unlike the other two journals, which are mostly in a narrative style, RCT is laid out in the form of a ship’s log, with descriptive language being used while they were in port, as was conventional.

In addition to the ship’s log, kept in the captain’s name, the master of a naval vessel also kept a journal, often the lieutenants and sometimes the midshipmen. With the Sirius, we have the ship’s log, kept in Phillip’s name; and journals kept by John Hunter, the ‘second captain’; by Micah Morton and James Keltie, the masters; William Bradley, the first lieutenant; and Gidley King, the second lieutenant.

A fair copy of Bradley’s ship’s journal, written up more than a decade later was acquired by the Australian National Maritime Museum in 2018, and a narrative version with maps and illustrations, drawn from the ship’s journal and at least one other narrative source, and probably intended for publication, was acquired by the Mitchell Library in 1924.[4]

RCT covers the period from 25 October 1787, when the fleet was at the Cape, through to King’s return to England on 19 December 1790. A note on the front page tells us that a copy of his journal for the first part of the voyage was sent home to the Admiralty from the Cape. This is not held by the Royal Collections Trust and it has not been located in the UK National Archives.

Provenance

It is unknown how this document made its way into the Royal Collection. An inscription on the first page reads, ‘Rec’d with Lt. King’s Letter dated 26 Decr 1790’, a week after his return to England, but this letter is not in the collection and it is unknown who wrote the notation.

The journal was first listed in the Royal Library during the reign of William IV (who as the Duke of Clarence had a naval career). He combined the private collections of his predecessors and made several acquisitions of his own to re-establish a Royal Library between 1832 and 1837, and the item cannot be confirmed as being in the royal collection prior to that time.

It seems likely that King wrote up RCT for transmission to the Admiralty – this is what he had done with his journal for the first part of the voyage, and it seems likely that he would have sent the Admiralty a journal in the form of a ship’s log rather than a narrative. But this interpretation is complicated by the fact that the Fair Copy was apparently loaned to the editors of Hunter’s Historical Journal by the Secretary of the Admiralty.

Journal-Writing

We now know that King kept a daily ship’s journal throughout the voyage, the original of which is missing. The three known versions, RCT, the Private Journal and the Fair Copy, all contain text copied from this journal. A comparison of RCT with the other Sirius journals for the first few weeks after leaving the Cape, tells us that he made his own calculations of latitude and longitude, distances and bearings, and did not rely on the ship’s log. In short, RCT is based on King’s own journal, personally written up day to day. It is unknown when he started to transcribe material into the RCT version, but probably during his time on Norfolk Island.

Once the Supply had arrived in NSW, King was kept busy, and in this period, his entries in the original journal seem to have been mostly confined to the weather and events on board the ship, with some rough notes being made in other notebooks about the events unfolding on shore.

On his arrival at Norfolk Island, King kept making entries in his ship’s journal, but he started ‘A Daily Journal of the Transactions &c on Norfolk Island’, or a ‘Diary of the Weather & State of Landing at Sydney Bay, the Monthly Account of Work Done & the Quantity of Grain Raised on the Island’, which makes up the second part of Volume 1 of the Private Journal and all of Volume 2. King stopped making entries in this journal in April 1790 when he arrived at Port Jackson on his way home to England.

It seems likely that King wrote up the first part of the Private Journal (which is a fair copy of his ship’s journal), and the first part of RCT while he was on the island, although we cannot be sure. The Fair Copy seems to have been started later.

RCT is often written in the present tense, suggesting that King was being careful to transcribe the original as it had been written. In that version, he always refers to Phillip as ‘Captain Phillip’ or ‘Mr Phillip’ prior to his departure for Norfolk Island. This is consistent with the practice for most (though not all) First Fleet correspondents and journal-keepers, who (in general) only referred to Phillip as the Governor once the Supply had arrived at Botany Bay. In the other two versions of King’s journal, he is anachronistically referred to throughout the voyage as ‘Governor Phillip’. (The original journal was written up each day or shortly thereafter, and would thus not contain such anachronisms.)

But King was not always this careful in avoiding anachronisms in the RCT. For example, under the entry for 26 January 1788, RCT refers to the cove where the settlement was established as ‘Sydney Cove’, a name which was not given to it until some days or weeks later. The Fair Copy also used this term, but the Private Journal simply refers to it as ‘the cove’. In copying text from the original into the Private Journal on this occasion, King chose to persist with the original language.

RCT also describes Port Jackson as Phillip’s destination when he first visited the harbour on the 21st of January. The other two versions refer to ‘Port Jackson and Broken Bay’. Phillip was probably intending to explore both inlets, but the documentary evidence is clear that Broken Bay was his preferred destination. Journals written prior to 23 January, the date when Phillip returned from Port Jackson and announced that it would be the site of the settlement, all describe his destination as Broken Bay. The journals and letters that describe his destination that day as Port Jackson were all written or rewritten after the 23rd.

In transcribing these three copies of his journal, King often drew on different details from the original, with the result that they often depart from one other in content. The Fair Copy also relies on other documents – letters sent and received, reports of criminal investigations and other notebooks. RCT and the Private Journal also use extraneous material, but not to the same extent.

Among other differences, there are places where the dates and times given for particular events disagree. This is understandable where the difference is one day or one hour, but it is more difficult to explain when they differ by several days or hours, as they sometimes do.

The Journal of the Supply

Almost none of the Supply’s journals have survived – two versions of a log written by the then Master, Christopher Holmes, from 10 November 1786 to 7 April 1787 (before the fleet sailed), a record of her homeward voyage in 1791-92, and summarised versions of her voyage across the Southern Ocean to NSW in 1787-88 (in King’s Private Journal and the Fair Copy), and her voyage to Batavia in 1790 (in the Fair Copy). The Private Journal and the Fair Copy often summarise or leave out entirely several days at a time – although in some places they have more detail than RCT.

RCT has daily journal entries for the time that King was on the Supply from 25 November 1787 until his arrival at Norfolk Island, and then his voyage from Norfolk Island to Port Jackson and Batavia in 1790. This additional information will mostly be of interest to maritime historians. We learn, for example, that on 10 December 1787, on her passage to New South Wales, the tiller of the Supply was sprung, and that an iron one was shipped while the other was repaired. This detail is not in either of the other versions.

RCT also has more information about the days of bitterly cold winds which they experienced in the run-up to Christmas 1787, it has more to say about the whales which they saw in crossing the Southern Ocean, and King incorporates into RCT a number of sketches which he made of the NSW coastline as they drew closer to Botany Bay.

The Flag-Raising Ceremony

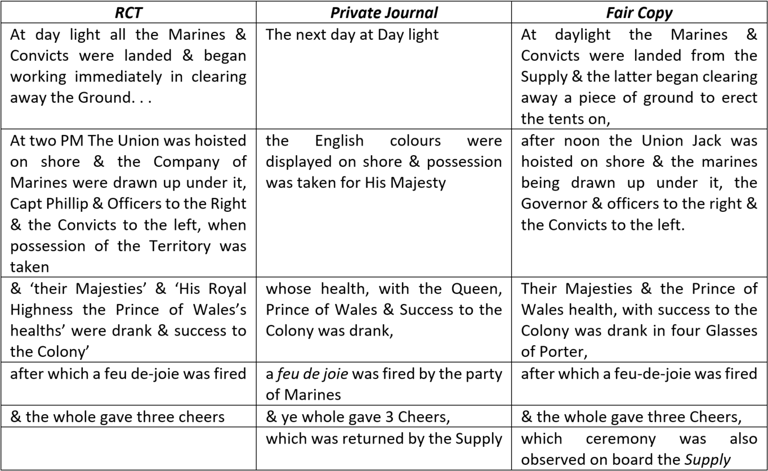

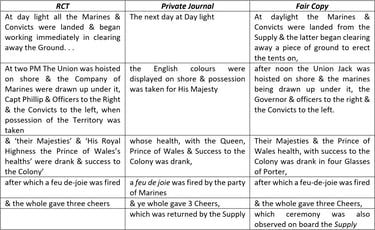

One of the most important insights from RCT is that the flag-raising ceremony took place on the afternoon of 26 January 1788 and not in the morning. The Fair Copy (and all other First Fleet sources) refer only to a ceremony in the afternoon. The Private Journal refers only to a ceremony in the morning, but because it was thought to be the original, and because King is the only (known) journal-keeper who was actually present at the ceremony, some historians had concluded that it should be given primacy. (Others have hedged their bets by arguing that there might have been two ceremonies.)

RCT is virtually identical to the Fair Copy in describing the ceremony, and like the Fair Copy, it records it as having taken place in the afternoon. In fact, RCT gives a precise time when the ceremony commenced – 2pm (while the Fair Copy only locates it ‘after noon’). This is broadly consistent with the recently-discovered letter of the First Fleet mariner, John Campbell, who wrote that preparations began at 3pm. Other First Fleet sources have been interpretated as saying that the ceremony took place in the evening around the time the Sirius arrived off the cove.

Analysis of the text of these three versions suggests that in transcribing the words into the Private Journal, King left out a passage which described the work that had been done throughout the day of the 26th. This created the impression that a ceremony had taken place in the morning.

Other Insights

There is a significant amount of detail in RCT that is not in the other versions – which will be of interest to historians and genealogists but probably not to the general public – such as additional information about the offences for which some of the convicts on Norfolk Island were punished, and the assistance which King gave to convicts and freemen who were willing to settle there.

But the following might be of more general interest:

Arrival in Port Jackson: The RCT version tells us that on sailing into Port Jackson on the afternoon of 25 January, the Supply was at first ‘warped’ – that is, moved forward by the use of anchors carried out in the ship’s boats, thrown overboard and then hauled in. This reveals a sense of caution on Phillip’s part, although once they were clear of some rocks that lay close to the harbour’s entrance, the sails were unfurled.

And when they anchored in the cove that night, King wrote that they could distinctly hear the evening gun of the Sirius, which was still at Botany Bay. This small detail does not appear in the other versions, and it gives us some idea of the profound shock which these noisy intruders brought to the traditional inhabitants and the native fauna.

A Stockade for the Livestock: Most of the activity in the first few days of the settlement lay on the western side of the stream which divided the camp, where the marines and the majority of the convicts were based. RCT indicates that as early as the 27th, a day after landing, men were employed in erecting a stockade on the east side of the cove (now known as Bennelong Point), where the livestock would be held. An entry in RCT for the 28th says that the stock belonging to the colony were landed and ‘all put on the East side of the Cove it being fenced across’, which implies that work had been done the day before.

The same entry says that the male convicts were landed on the 28th and were ‘all employed Clearing away ground for the Encampment, & Garden ground’. We knew from the Private Journal and the Fair Copy that convicts were involved in digging up ground for the Governor’s garden (on the east side of the stream) on the 29th, but RCT makes it clear that the scrub was already being cleared the day before.

Visit to La Perouse: King’s account of his visit to La Perouse at Botany Bay in early February 1788 contains some fascinating detail not found in the other versions. King was concerned not to cause offence by asking too many questions about the expedition: when he mentioned this to La Perouse, he was told that he could ask any questions he liked, and the French commodore offered to take down his journals for him to read. King wrote that he declined, but it seems that he did read an account of a fatal attack on some of the French boats while they were watering the ships at Maouna, one of the islands in what is now known as Western Samoa. This was of particular significance because La Perouse had given King the coordinates for the island, and suggested that as long as they were careful, the British settlers might obtain fresh provisions there.

The Commissioning Ceremony: One of the enigmas about the two previously-known versions was that the Private Journal does not mention the ceremony held on the 7th of February where Phillip was sworn in as Governor and British law was formally proclaimed, and the Fair Copy initially located this gathering on the 30th of January, then shifted the date to the 3rd of February. There is no question as to what date the ceremony was held, and RCT locates it on the correct date.

This serves to illustrate the importance of historians and writers studying all available sources when researching the First Fleet and the early years of the colony, where there are so many different journals covering the same events. It is no longer acceptable to rely on just one or two.

King’s ‘Family’: It has long been known that King fathered several children by a convict, Ann Inett. Their eldest boy was delivered on 8 January 1789, the first child to be born on Norfolk Island, and in recognition of the occasion, King named him Norfolk.

RCT tells us that King baptised the child himself after the Divine Service held on the 18th of January. And another journal entry provides us with some insight into how King felt about Inett and their infant son: on 1 August 1789, King wrote that they ‘Killed a Boar belonging to Government weight 40 lbs for which 40 lbs of Salt Meat is deducted from my familys Allowance’.

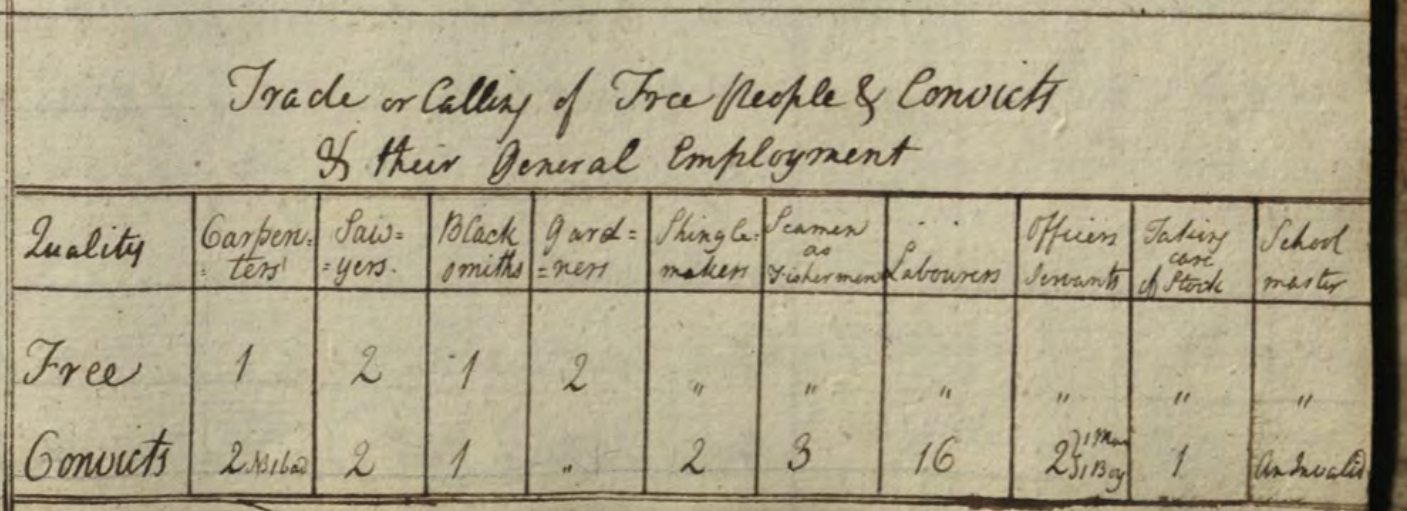

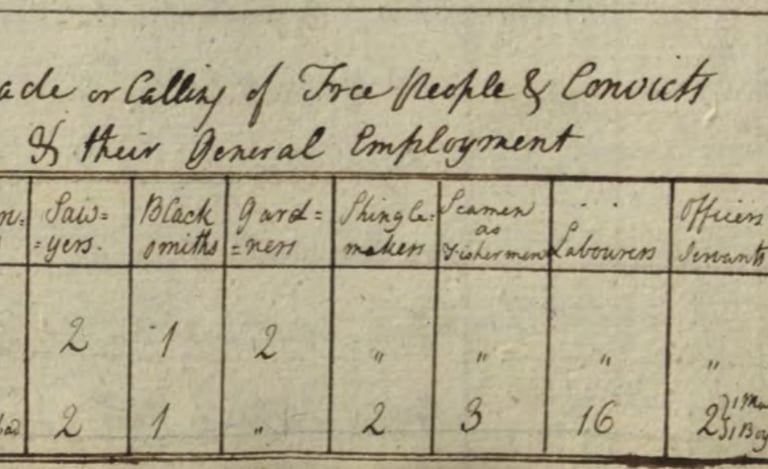

Statistics for Norfolk Island: RCT has a table listing the free people who arrived on Norfolk Island with him in March 1788, along with the number of convicts and the quantity of provisions. He periodically updated this table as more people arrived, in some cases including a description of their trades. The following, for example, is from October 1788, after the Golden Grove arrived:

Other Details on Norfolk Island: All three journals differ in the details they provide about life on the island, and in writing about the early history of the island, historians will now need to study them all. For example, in RCT, but not in the other versions, King discusses the sap of a tree which blinded the sawyers when they got it in their eyes.

2 Men blinded by the sap of a Tree, which gets into their Eyes as they cut the trees down, & occasions a violent burning pain for two or three days. The sap is quite White, & on the least cut in the bark of the tree it flies out very fast. It is not the [illegible]. The Surgeon finds the best remedy is to apply Florence Oil to the eye, which in general removes the pain & inflammation in three days.

Accessing the RCT Version

Somewhat delayed by the death of Queen Elizabeth II, the RCT version was scanned in December 2022, but uploading the images was further delayed by the unexpected resignation of a technician and technical upgrades. It was published on the RCT’s Georgian Papers micro site in July 2024.[5]

______________________

[1] https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/YK5QKXXn

[2] https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/Yezd5QA9; https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/nQR2NkG1 and https://adc.library.usyd.edu.au/view?docId=ozlit/xml-main-texts/kinjour.xml;collection=;database=;query=;brand=default.

[3] Royal Collections Trust, RCIN 1047381.

[4] https://collections.sea.museum/objects/202631/log-of-hms-sirius-1787--1792?ctx=8917d679-1426-4339-afad-6241ced4905d&idx=0 and https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/YEGmpNKn.

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.