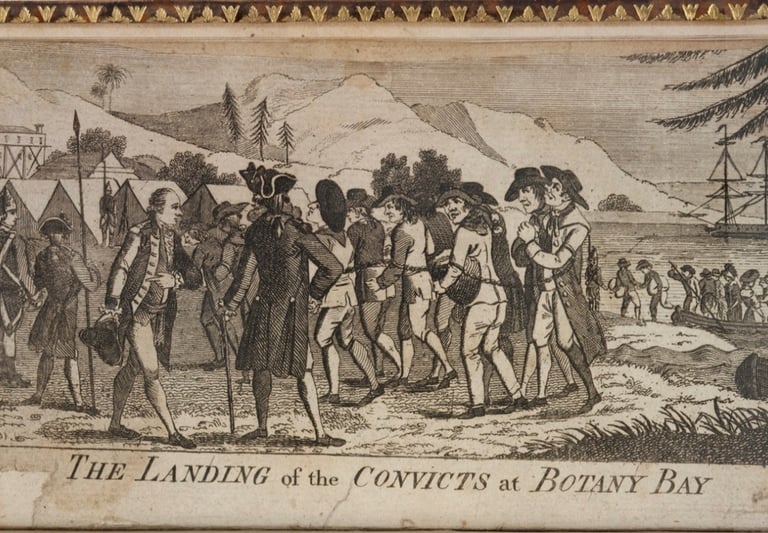

A Depiction of the First Fleet Marines in a 1789 Engraving

An engraving of the early settlement found in a pirated copy of Watkin Tench's 'Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay' is historically inaccurate in many respects, but useful for understanding how the marines were dressed.

Gary L. Sturgess

2/19/20266 min read

The Engraving

No image of private marines in the five years they were in the NSW penal colony is known to exist. (There are several paintings from early 1791 which might show marines, but which might also be NSW Corps.)

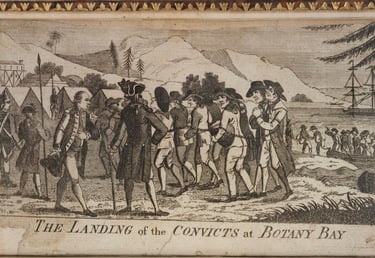

The engraving above, of convicts coming ashore in Sydney Cove[1] in January 1788, is fanciful, but it is useful in exploring how the marines looked.

This image is the frontispiece of a pirated copy of the first edition of the ‘Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay’, written by a marine Captain Lieutenant, Watkin Tench. It is 64 pages in length, and somewhat shorter than the original, which has 146 pages.

The earliest notice of the proposed publication of Tench’s book was in the London papers on the 28th of March, days after the return of the first of the First Fleet transports. The publisher, Debrett’s of Piccadilly, released the book for sale to the public on the 4th of April, and it was an instant success. On the 25th of May, Reverend Weeden Butler, of Cheyne’s Walk, Chelsea, who was the uncle of Daniel Southwell, a midshipman on HMS Sirius, wrote to his nephew that he had already read Captain Tench’s book, which ‘pleased me much’. ‘His volume is well received.’

The title page of the pirated edition has no details about the publisher or the year of publication, but it is thought to have been made shortly after the release of the original. Only two copies of this pirated version are known to exist, and the other is missing the frontispiece.

The artist who made the sketch is unknown, but he or she had never visited NSW, nor (it seems) read Tench’s book. It shows substantial buildings in the background at the same time as convicts are being landed on first arrival. The prisoners are depicted coming ashore in chains, when in truth, they had not been ironed since leaving England. And the surrounding landscape does not resemble Sydney Cove in the slightest.

However, the drawings of the marines in this engraving are of interest, since they were evidently made by someone who was familiar with the officers and men of that service around this time. Sketches and paintings of marine privates in the years between the end of the American War of Independence in 1783 and the commencement of the Anglo-French Wars in 1793 are rare.

A Close Reading

The central figure in the engraving, with his back to the viewer, is meant to be the Governor, Arthur Phillip, who would have been imagined as wearing the blue coat of a British naval officer.

At the centre left, approaching the Governor, is a marine officer with bare head and receding hairline. He wears his dress uniform – an officer’s coat (which would have been scarlet in colour) with white facings, and silver epaulettes. There is a scarlet sash around his waist, and the ruffles of his shirt are evident at the neck and cuffs. He is wearing shoes and stockings without gaiters, which is how he might have been dressed for a portrait, and he carries a tricorn hat.

He is not wearing a cross belt or sword, although these are missing from many portraits of marine officers from around the American War of Independence. Nor is he wearing a gorget around his neck, one of the most visible indicators of a military officer, but these are also missing from a number of the portraits of marine officers around this time.

AI-colourised version of the officer, with the convicts removed from the background (Google Gemini. AI wrangler: Galen Sturgess)

His hair appears to be curled above the ear, which would make him an officer in a battalion company (that is, not a grenadier or light infantry).

The only contemporary (or near contemporary) portrait of a First Fleet marine officer is a miniature of Watkin Tench, made around 1787, which provides more detail of the top half of the uniform. Tench’s coat is buttoned up, but his epaulettes are clearly shown, and his ‘stock’ a black horsehair collar worn around the neck, which is not clearly shown in the engraving. The shirt frills are showing at the neck in both illustrations. Tench’s hair in this portrait is cropped just above the neck. This is most unusual and matches none of the regulation styles for battalion, grenadier or light infantry officers.

‘The Landing of the Convicts at Botany Bay’, frontispiece, An Officer of Marines, A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay, c.1789, State Library of NSW, SAFE/78/70

‘Captain Watkin Tench, 1787’, Watercolour miniature on Ivory, SLNSW MIN 579

Behind the officer at the left of the engraving are three soldiers – two marine privates and a sergeant. The privates are also in their dress uniform, with the characteristic madder red coats and white cross belts, the latter holding cartridge boxes on the right-hand side, and bayonet scabbards on the left (the scabbards not visible in this engraving). Like the officer, they wear white breeches not trousers, with white stockings to the knee, and shoes and half gaiters. They carry ‘Brown Bess’ muskets mounted with bayonets.

AI-colourised version of the other ranks, with the convicts removed from the background (Google Gemini. AI wrangler: Galen Sturgess)

On their heads they wear caps with badges at the front which extend above the crown. All of the First Fleet marines were issued with leather caps, and these would probably have had metal plates affixed. There are no clear images of these caps for battalion companies in this period, but the photograph below of a light infantry cap and badge in the Maritime Museum at Greenwich gives some idea of how they would have looked.

Marine Light Infantryman’s Cap, late 18th century, Royal Maritime Museum Greenwich

It is likely that the artist was intending to show battalion marines, and it seems more likely that they would have worn cocked hats with their full-dress uniform. The watercolour sketch below of a marine sentry on HMS Pallas in 1775 is close to what the First Fleet marines would have been wearing on parade.

Gabriel Bray, ‘'A Centinel on the Pallas's Gangway, Jan’y 1775', Royal Museums Greenwich, PAJ20

In the engraving from the unauthorised edition of the ‘Narrative’, a sergeant can be seen to the right of the two privates, wearing a tricorn hat and holding a spear-like halberd or spontoon. There is no mention of halberds in the First Fleet records, but there is also no mention of the sergeants being issued with swords, and it is reasonably certain that they were. At this time, halberds were a symbol of rank, and an instrument for straightening the ranks, not a weapon.

AI-colourised version of the other ranks, with the convicts removed from the background (Google Gemini. AI wrangler: Galen Sturgess)

In the background of the engraving is a neat row of tents guarded by a sentry (whom AI has given a cocked hat without being asked). Almost certainly, the artist was showing the marine encampment on landing (although it is located too close to the shore).

This encampment is similar to the one portrayed in the background of a portrait of 2nd Lieutenant Paul Crebbin, recently acquired by Manx National Heritage on the Isle of Mann, and dated to around 1780.

AI-clarified version of the background of a portrait of Paul Crebbin, c.1780, Mann at War Gallery, Isle of Mann. (Google Gemini. AI wrangler: Galen Sturgess)

In Summary

I’ve always been inclined to overlook this engraving of the landing of the convicts at Botany Bay because of its historical inaccuracies, but on studying it more closely, I have concluded that, while it has limitations, it can still give us a better understanding of how the First Fleet marines looked.

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.