A Convict Beachcomber

Australians have shown little interest in what happened to convicts who left the colony, either as escapees or as emancipists with permission to leave. Many returned to Britain or Ireland, but a number wound up at the Cape of Good Hope or in India, or as beachcombers on one of the islands of the Pacific.

Gary L. Sturgess

8/30/20254 min read

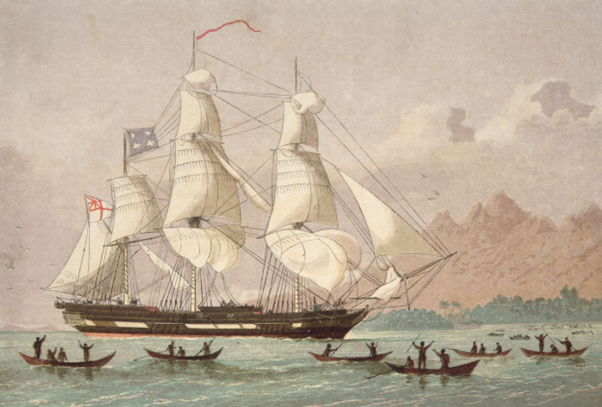

The Duff arriving at Tahiti (1797), lithograph by Kronheim & Co, 1820s

In his classic, Two Years Before the Mast, first published in 1840, Richard Henry Dana invented the word ‘beachcombers’ to describe the European mariners and emancipated or escaped convicts who had settled on the islands of the South Pacific, seeking a home away from civilised society.

John Henry Eagelston, the captain of an American ship which visited the Pacific in the 1830s, wrote that the Europeans who had taken up residence in Samoa were ‘Mostly convicts from Sidney and devils of the blackest stamp’. This perception – that they were largely escaped convicts – was common at the time. While not entirely correct, it was often the case in the 1790s and early 1800s.

The earliest known convict beachcomber, and one of the earliest European settlers on Tahiti, was Solomon Pollock, an Ashkenazi Jew and escaped convict who arrived in 1792 on the Third Fleet whaler, Matilda. He played an important role in the tribal wars which brought the Pomare family to prominence (and who would go on to become the kings and queens of Tahiti). Pollock's ultimate fate is unknown.

This paper is concerned with another of the early beachcombers – Benjamin Ambler, a time-expired convict who arrived in Tonga in 1796, one of the first Europeans to settle in those islands. He died there four years later, and unlike Pollock, we do know something of his life and death.

Ambler had been born at Shadwell, one of the maritime villages to the east of London, the son of a weaver from Norwich. In 1787, when he was 16 years of age, he was convicted of stealing clothing from two spinsters in their home, and sentenced to seven years transportation. Attempting to benefit from legal presumptions in favour of young offenders, Ambler claimed he was only 14 years old. The judge was clearly unimpressed with his story, and given that he was sentenced to transportation for this offence, it is likely that he already had a criminal record.

After being held in Newgate for almost two years, Ambler was shipped on board the ill-fated Neptune, the Second Fleet transport which had a mortality rate (among the men) of around 50 percent. Whilst he survived, it would be surprising if he was not embittered by the experience.

Nothing is known of his time in NSW, other than that on the 28th of September 1794, the day he competed his sentence, he served as a witness at a wedding ceremony in Sydney, signing his name confidently in the register. Three months later, he was bound for Bengal as a 'landsman' in the crew of the Surprize.

On arrival at Calcutta, the authorities refused Ambler permission to stay. The East India Company tightly regulated immigration into their Indian domains, and they were strongly opposed to having former convicts take up residence there. He returned to Port Jackson, probably in the Arthur, a Bengal trader, in January 1796. There he immediately joined the Otter, an American trader headed for the north-west coast of America.

Captain Ebenezer Dorr touched at Nomuka in the islands of Tonga in March, where Ambler left the ship along with one of the crew, an Irishman named John Connelly, and four other ‘passengers from Port Jackson’. Three of these men were shortly thereafter taken on board by another American ship; the fourth was a young Irish escapee named Morgan Brien, who chose to remain.

Ambler and Connelly subsequently relocated to the main island of Tongatapu, where they were discovered in April 1797 by missionaries brought to Tonga by the Duff, Captain James Wilson, a vessel commissioned by the London Missionary Society.

By that time, Ambler was already fluent in the Tongan language, and in the early months of the missionaries’ time on the island, he acted as an interpreter and interlocutor in dealing with the local chiefs. He dressed as an islander and was living with three or four women, one of whom was the daughter of a powerful (and ruthless) chief, Tuku’aho, who was Ambler’s patron. According to the missionaries, he beat these women brutishly and stole from the islanders.

When ‘the brethren’ stopped giving Ambler and Connelly iron tools, the beachcombers started undermining the trust that was developing between the missionaries and several of the chiefs. In May, they were joined by Morgan Brien, who had been living on one of the islands to the north.

Ruthlessness and deception was not confined to one side: the missionaries conspired to kidnap these interlopers and have them carried away by the Duff. Wilson was successful in taking Connelly, but Ambler and Brien avoided capture.

When the Mercury, another American trader, touched at Tongatapu the following year, on her way from Port Jackson to the North-West Coast, seven crew members – six Europeans and one Hawaiian – left the ship. One of them aligned himself with the missionaries and the other six joined ‘Ambler’s party’ (as one of the missionaries described them). The beachcombers continued to undermine the chiefs’ trust in the missionaries, so successfully that at one stage, the paramount chief gave approval for them to be killed.

Civil war broke out in April 1799, resulting in several of the missionaries being killed and the remainder fleeing to Port Jackson. It is likely that the beachcombers played some part in these wars, but the extent of their involvement is unknown. The following year, while the war was still raging, Ambler was killed for speaking disrespectfully of a neighbouring chief, and for his attempts at stirring up dissension.

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.