A Colonial Bacchanal

Renowned Sydney historian Grace Karskens has rejected accounts of an orgy on the evening of the 6th of February 1788, the first night that the female convicts were onshore. But there is more to this story than she acknowledged.

Gary L. Sturgess

2/1/20254 min read

British law wasn’t proclaimed at the flag-raising ceremony held in Sydney Cove on the 26th of January 1788, but at a much larger gathering on the 7th of February, when Captain Arthur Phillip was sworn in as Governor. As we approach the 237th anniversary of that ceremony, we revisit the orgy that is supposed to have occurred the night before, when the convict women were finally brought ashore from the Lady Penrhyn.

Manning Clark was the first historian to focus on this event, followed by Robert Hughes, Tim Flannery and Peter Fitzsimons. Grace Karskens has rejected it, insisting that the surgeon of the Lady Penrhyn, Arthur Bowes Smyth, the only individual to record the drunken revelries, could not possibly have seen what was happening on shore.

As she tells the story, the Lady Penrhyn was out in the harbour that night, not in the cove, and it would have been impossible for Bowes Smyth to have witnessed celebrations up the south-west end of the cove.

That isn’t right: Lieutenant William Bradley’s drawing of the cove on the 27th of January shows the Lady Penrhyn moored well inside the cove, on the east side. Bowes Smyth wrote that they moored at the head of the cove – which would place them even closer to the women’s camp – and given that they had landed around a hundred female convicts that afternoon, it would have been impractical to anchor outside the cove.

There is no question that Bowes Smyth was watching from a distance, and he does not spell out the details of the debauchery – we are given the literary equivalent of the asterisks inserted in schoolboy copies of Suetonius’s ‘Lives of the Caesars’: ‘it is beyond my abilities to give a just description of the Scene of debauchery & Riot that ensued during the night’. [1]

But given that the convicts had been confined to their ships for a year or more, the vast majority of them without access to spirits or the opposite sex, it is not difficult to imagine that they might have partied that night. There is room for debate about how raucous and unruly it was, but given that the convicts had access to liquor, it doesn’t seem unreasonable to conclude that some of them let their hair down.

As the marine officer, Watkin Tench, wrote:

'While they were on board ship, the two sexes had been kept most rigorously apart; but, when landed, their separation became impracticable, and would have been perhaps wrong. Licentiousness was the unavoidable consequence, and their old habits of depravity were beginning to recur.' [2]

Twenty percent of the women had convictions for prostitution-related offences – prostitution wasn’t a transportable offence, but one in five of the women had been prosecuted at some point for stealing from a man up a back alley or in bed. Even if there were only a handful, that would have been enough to spice up the party.

Other sources tell us that in the days immediately following, the prostitutes were doing a roaring trade in the women’s camp, and it is difficult to understand why they wouldn’t have been open for business that night as well.

(For example, on the 11th of February, the marine lieutenant, Ralph Clark, wrote: ‘. . . no Sooner has one man gone in with a woman but another goes in with her.’ The following day, after a number of seamen were drummed out of women's camp, he wrote that he hoped it would be a warning against them coming into the ‘whore camp’. [3])

And then there is circumstantial evidence which led feminist historians (and Robert Hughes) to claim that some of the women were sexually abused that night.

In his address to the convicts the next day, immediately after he had been sworn in as Governor, Phillip said that he had:

'. . . particularly noticed the illegal intercourse between the sexes as an offence which encouraged a general profligacy of manners, and was in several ways injurious to society.' [4]

As a commander of naval vessels, Phillip accepted prostitution as a fact of life: he would not have regarded that as unlawful. But he doesn’t seem to be referring to rape – this was ‘an offence which encouraged a general profligacy of manners’.

The surgeon on the Sirius quoted the Governor as saying:

'. . . there were a number of good men among them, who, unfortunately, from falling into bad company, from the influence of bad women, and in the rash moment of intoxication, had been led to violate the laws of their country, by committing crimes which in the serious moments of reflection, they thought of with horror & shame, and of which now, they sincerely repented. . .' [5]

This suggests that there had been some kind of investigation late that night or early on the morning of the 7th. Phillip is referring to specific individuals, since he speaks of good men who have reacted with horror and shame when confronted over their behaviour. This was more than a mere breach of social convention, but not something that justified a criminal prosecution.

Unless other documents come to light, we will never get beyond the asterisks, but weighing up the evidence, I am inclined to the view that something happened on the night of the 6th of February that was deeply embarrassing to Governor Phillip.

______________

[1] Arthur Bowes Smyth, Arthur Bowes Smyth, ‘Journal of Arthur Bowes Smyth, 22 March 1787 to 8 August 1789’, NLA MS4568, 6 February 1788. 6 February 1788.

[2] Watkin Tench, A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay, 2nd edition, London: J. Debrett, 1789, pp.62-63.

[3] Paul G. Fidlon, et al (eds.), The Journal and Letters of Lt. Ralph Clark, 1787-1792, Sydney: Australian Documents Library, 1981, p.97.

[4] The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay, London: John Stockdale, 1789, p.67.

[5] George Worgan, Journal of a First Fleet Surgeon, Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1978, p.35.

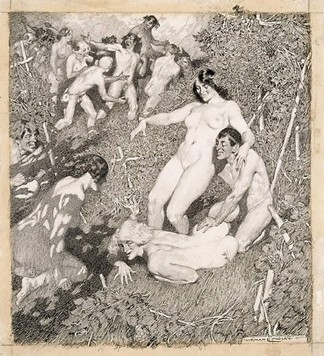

Norman Lindsay, 'Bacchanal', 1905

Contact us

Connect with us

Botany Baymen acknowledges the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and respects their connection to land, water and community.

© Botany Baymen 2024. All rights reserved.

You may download, display, print and reproduce this content for your personal or non-commercial use but only in an unaltered form and with the copyright acknowledged.